Robert here w/ Distant Relatives, exploring the connections between one classic and one contemporary film.

What is it about the American West that endures? No other specific time and place has been so ubiquitous in film that it's spurred its own genre. There's no genre for colonial films, or films about the depression. There's no genre for medieval movies or ancient Egypt. The closest we come are "period films" (more of a general catagorization than a genre), epics (a designation that depends on more than mere setting) and war movies (narrowly limited depending on the war, but so many wars to choose from) but none of them have the same lure as the Western. America being as young as it is, was founded during a time of general civility. Yes it was born out of Revolution, but the civilization itself was defined by men in suits and manners and polite society. We had no knights on crusades, no mythical quests, no wild lawless wilderness to tame... except when we did, out in the West. And thus, the Western has become the defining genre of American Mythology. Our two films, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford are about a time when what was known as "The West" was dying and thus in order to endure had to be mythologized. Both feature the symbolic death of a figure who represents the times. And both start with the arrival of an outsider.

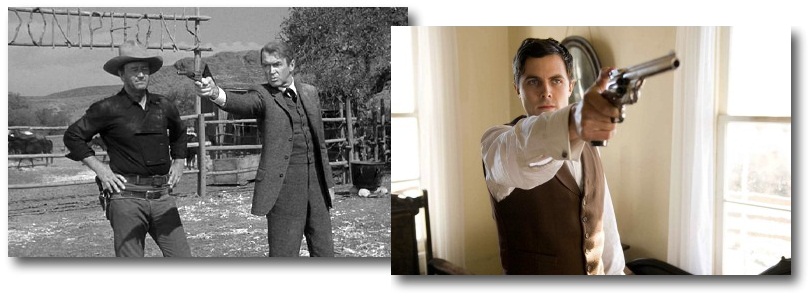

The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford is less about James (Brad Pitt) and more about Bob Ford (Casey Afflect), a young man who grew up on tall tales of the legendary outlaw Jesse James and now finds himself part of the man's much diminished gang. Call him the original fanboy, obsessed with a reality and an excitement that cannot possibly exist outside of his own imagination. Ford learns that James, despite being well over the hill crime-wise is still quite dangerous and out of fear and paranoia becomes the man who shoots James dead (no spoiler needed I hope) and comes to play a new part in the legend he believed in when he was young. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance follows James Stewart as Ransom Stoddard, who arrives in Shinbone a town being menaced by the outlaw Liberty Valance (Lee Marvin). Stodden befriends a local (John Wayne), falls for the woman he's courting and eventually sets up residence in the town determined to help nurture it into the union through representative democracy but not until an inevitable showdown with Valance, in which, as legend came to have it, the ernest amateur Stodden prevailed over the evil gunslinger.

Stylistically these films couldn't be more different. Jesse James with its langorous pacing and expressive Roger Deakins' cinematography draws comparisons to Terrence Malick. Liberty Valance was one of the most workmanly crafted films from great workman director John Ford. This was no The Searchers with its sweeping vistas and color photography. Valance was shot on sound stages and most of the action takes place indoors or within the confines of city limits. Structurally they're more similar. Our outsiders enter into the waning days of an already mythologized west and find that the reality is not what they've been lead to believe, take action to affect that reality and get lost again in the myth. About this process, both films are deeply cynical. And where better to start finding this cynisism than in their titles. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance is a "wink wink" reference to the central mystery of the film and the fact the man who "shot" Liberty Valance is not most likely the man who actually shot Liberty Valance. The Jesse James title is even more incisive, inserting loaded terms like "assassination" and "coward" into it's otherwise expository explanation of the entire plot.

From there it gets worse. Jesse James postulates as Bob Ford learns that the west wasn't filled with adventures, just rampages and Liberty Valance suggests that the time's celebrated heroics were really acts of desperation. Our "heroes" (in the heaviest of quotes) suffer not only from the lawlessness and chaos around them but from the world's determination not to believe anything but the mythologized old west they've come to love. In Liberty Valance, after the old west and it's human embodiment dies, all that's left is an emasculated old public official, not much more useful than the world he came into. In Jesse James, after the death of Jesse and subsequently the west, all that's left is the reviled Ford, celebrated because he's reviled and then reviled more because he's celebrated. A murderer of a murderer more despised than the man he killed because the man he killed represented something exciting and romantic. What Ford represents is the banal truth, which people will refuse to believe at any cost. Similarly Stodden's vanquisihing of Liberty Valance is a great story, the truth of which couldn't matter less. "This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend," declares a newspaperman to him at the end of the film.

Just as there's no other genre quite like the Western, no other genre is quite so fond of deconstructing itself. We're almost to the point where the de-mythologizing of the Old West has circled back and become part of the myth again. But in all of cinema history, few Westerns are as self aware, self-referential, and self-contained as these two stories about infamous legends, and the men who killed them.

Other Cinematic Relatives: My Darling Clementine (1946), Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1968), Three Amigos! (1986), Sukiyaki Western Django (2007)