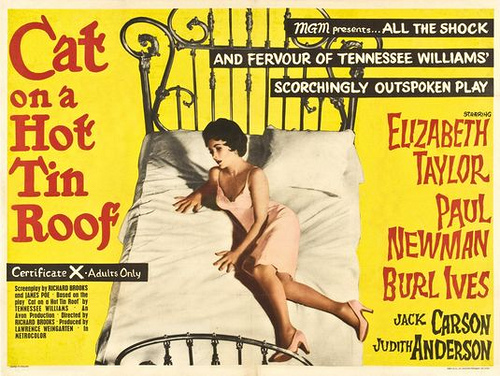

Robert G from Sketchy Details here to discuss the real star of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof for this Tennessee Williams Centennial Week. The beauty of the fifties screen adaptation of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof is not in the quality of the performances, set design, or cinematography. It comes from the tightly-wound dialog and plot structure adapted from Tennessee Williams' stage play.

Elizabeth Taylor and a No Neck Monster

Elizabeth Taylor and a No Neck Monster

For this one-day tale of adults acting as foolish as children, the true nature of the story is revealed when the characters pull away from the lines they learned by heart. The dialog is a mask used by the characters to hide their true feelings about everyone else. Even something as ridiculous as Maggie's (Oscar nominated Elizabeth Taylor) constant put-downs of the "no-neck monsters" is nothing but an act of misdirection.

Brick has major emotional hurdles to leap.Every major character in the film, regardless of age, is no more mature than the parade of children singing and dancing throughout the estate. The adults fire off sharp words at each other to draw attention away from their own insecurities. They all play into the roles defined for them by the family. If Brick (Oscar nominated Paul Newman) can't be the football star he once was, he will be the most dedicated alcoholic the family has ever gossiped about. The same goes for Big Daddy (Burl Ives) as the no-nonsense patriarch of an empire, Big Momma (Judith Anderson) as the unyielding caregiver, and even Mae and Maggie as the manipulative money-hungry wives. Talking about the roles they're playing only encourages each of them to act out the roles with more energy and commitment.

Brick has major emotional hurdles to leap.Every major character in the film, regardless of age, is no more mature than the parade of children singing and dancing throughout the estate. The adults fire off sharp words at each other to draw attention away from their own insecurities. They all play into the roles defined for them by the family. If Brick (Oscar nominated Paul Newman) can't be the football star he once was, he will be the most dedicated alcoholic the family has ever gossiped about. The same goes for Big Daddy (Burl Ives) as the no-nonsense patriarch of an empire, Big Momma (Judith Anderson) as the unyielding caregiver, and even Mae and Maggie as the manipulative money-hungry wives. Talking about the roles they're playing only encourages each of them to act out the roles with more energy and commitment.

It is only when the constant talk of "Big Daddy," "cats," and "Skipper" gives way to the overbearing discussion of "mendacity" that the film comes into focus. Brick isn't the only person trying to escape the lies of the Pollitt Empire; they all are. Every single member of the family is sick of the roles, game play, and war of kind facades with bitter tongues. They don't want to play into it but they don't know how to escape it. Even the doctor plays into the game of lies when he tells everyone except for Big Momma and Big Daddy that Big Daddy's dying from cancer.

The constant repetition in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof is an effective device: Brick always plays with his glass in a certain way, Maggie wipes her hands and arms, Mae (Madeleine Sherwood) always conducts the children's songs in the same way, Big Daddy dismisses everyone with the same tone and arm wave. The repeated discussions of child rearing, marriage, Big Daddy's health, and the titular cat metaphor are just extra tools used to keep each member of the family in their respective role.

These words and actions are choreographed to create an artificial sense of normalcy that will eventually give way to more believable mannerisms, speaking patterns, and interactions when the lies stop.

The only thing that can break the pattern is to discuss the environment of lies itself: mendacity. Brick blames it for his drinking, but Big Daddy won't accept that as an answer because Brick is expected to play the role of a drunk. One by one, the lies that support the clan are torn apart until only the true nature of each character is left standing. There is no more glass spinning or arm waving; there is only a family transitioning into better fitting roles. Tennessee Williams Cat on a Hot Tin Roof won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. It lost the Tony Award to The Diary of Anne Frank in 1956. The film version was nominated for 6 Oscars losing Best Picture to Gigi. Burl Ives won the Supporting Actor that year but for The Big Country instead. "Big Daddy" surely had something to do with that.

Tennessee Williams Cat on a Hot Tin Roof won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. It lost the Tony Award to The Diary of Anne Frank in 1956. The film version was nominated for 6 Oscars losing Best Picture to Gigi. Burl Ives won the Supporting Actor that year but for The Big Country instead. "Big Daddy" surely had something to do with that.