Craig (from Dark Eye Socket) here with another Take Three. Today: Max von Sydow

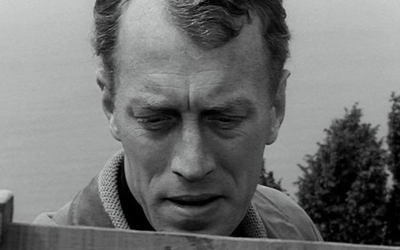

Take One: Hour of the Wolf (1968)

It goes without saying, of course, that a von Sydow Take Three wouldn’t feel right unless one of them was an Ingmar Bergman film. All three could’ve been, but the aim is to err on the side of variety whenever possible. They made 11 films together: The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries, The Magician, The Virgin Spring, Through a Glass Darkly, Winter Light, Shame and The Passion of Anna are all classics. But Hour of the Wolf, in which von Sydow plays a painter losing his grip on his sanity, doesn’t always get the high mention it deserves. It contains some of von Sydow’s best work in any film, for any director.

With his handsomely regal face, von Sydow boldly dominates the film. His sinisterly unhinged stillness and almost unreadable presence cement the notion that he’s a tormented artist uncertain of his place in the world. He's visited by people, possibly demons in human disguise, who embody his trauma, his shame. In a possibly imagined, probably symbolic, but definitely surreal dinner scene von Sydow’s deathly wan countenance crumples in extreme close-up. His mind seems to deteriorate due to the inane banter of the chattering souls surrounding him. (No one said Bergman’s personal parables were cheery.) Von Sydow masters depression and disgust like breathing and underplays his scenes like a covert pro. With complete skill von Sydow does as much as an actor can to attempt to place the viewer inside his character’s brain.

Take Two: The Exorcist (1973)

I don’t think it’s via Jeez himself, but, Christ!, the power of character acting compels me... to write about Father Lankester Merrin in The Exorcist for this Take.

Demonic Possession and Demonic Behavior after the jump

By the time we see von Sydow's faithful Father roll up in a cab to stand in front of the MacNeil house - poster image! - we’ve seen him fret through an archaeological dig for a bestial statue in Iraq. We know how peaceful and dedicated he is to uncovering the evil of Pazuzu (the maybe-mythical demon possessing Linda Blair’s Regan), having encountered him and many other devilish ids before. But this exorcism’s a doozy, and enough to give him a heart attack.

The often-used ‘expert called in to help’ plot device in horror movies was best exemplified in von Sydow’s collared demon expeller. His entrance is formidable and a long time coming: bathed in awe, he slowly emerges from the dark night. But as soon as he sets foot inside the MacNeil home the devil upstairs hollers and gurgles forth his objection. As the most distinguished and lauded actor in the cast it was baffling that he was the only one of the four main players to not receive an Oscar nomination. (His only nod so far was for 1987’s Pelle the Conqueror.) It’s in the actual exorcist-performing scenes where von Sydow shines best. Throughout all the levitating beds, sucked appendages in hell and head-spun vomit (which he calmly wipes off his face without so much as blinking), von Sydow commands the screen as he does that chilly bedroom: with masterful assurance.

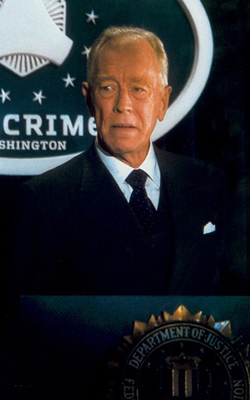

Take Three: Minority Report (2002)

A quick pre-Take warning: spoilers below

There are a fair few science-fiction films nestled among the Bergmans, the arthouse masterpieces, play adaptations and highly-regarded dramas in von Sydow’s filmography. He’s not averse to genre filmmaking, thus Death Watch, Dreamscape, Dune, Until the End of the World, Needful Things, Judge Dredd, What Dreams May Come and of course his Ming the Merciless in Flash Gordon dot the resume. However, his best sci-fi appearance was in Spielberg’s Minority Report.

There are a fair few science-fiction films nestled among the Bergmans, the arthouse masterpieces, play adaptations and highly-regarded dramas in von Sydow’s filmography. He’s not averse to genre filmmaking, thus Death Watch, Dreamscape, Dune, Until the End of the World, Needful Things, Judge Dredd, What Dreams May Come and of course his Ming the Merciless in Flash Gordon dot the resume. However, his best sci-fi appearance was in Spielberg’s Minority Report.

He gets an ‘and Max von Sydow’ credit after all the other main cast members, so he must be important. And he is. As Lamar Burgess, director of the Precrime division in the imagined Washington of 2054, he’s running (police) man Tom Cruise’s mentor, father figure and boss. He’s the shady villain of the piece, too. We only find that out later, however, in a cunningly performed scene when von Sydow permanently silences snooping agent Colin Farrell. Von Sydow’s delicious line delivery and expressionistically-lit face combine perfectly to signal just how warped and duplicitous Lamar turns out to be. One of his best scenes comes near the end after Lamar’s been found out (as a result of the twisty-turny plot). He’s confronted with an almost inescapable quandary: don’t kill Cruise, proving the precogs are wrong, destroying his beloved Precrime division; or kill him, thus proving them right (and himself guilty) and Precrime continues. His facade collapses like a precarious puzzle. Here, as earlier, we see futility written in his expression. It’s a subtle performance full of crooked intricacies. Only a seasoned ace like von Sydow could pull it off in just the right way.

Three more key films for the taking: The Virgin Spring (1960), Hannah and Her Sisters (1986), Intacto (2001)