Robert here w/ Distant Relatives, exploring the connections between one classic and one contemporary film. This week the second in a three part series on how one classic film can have many children.

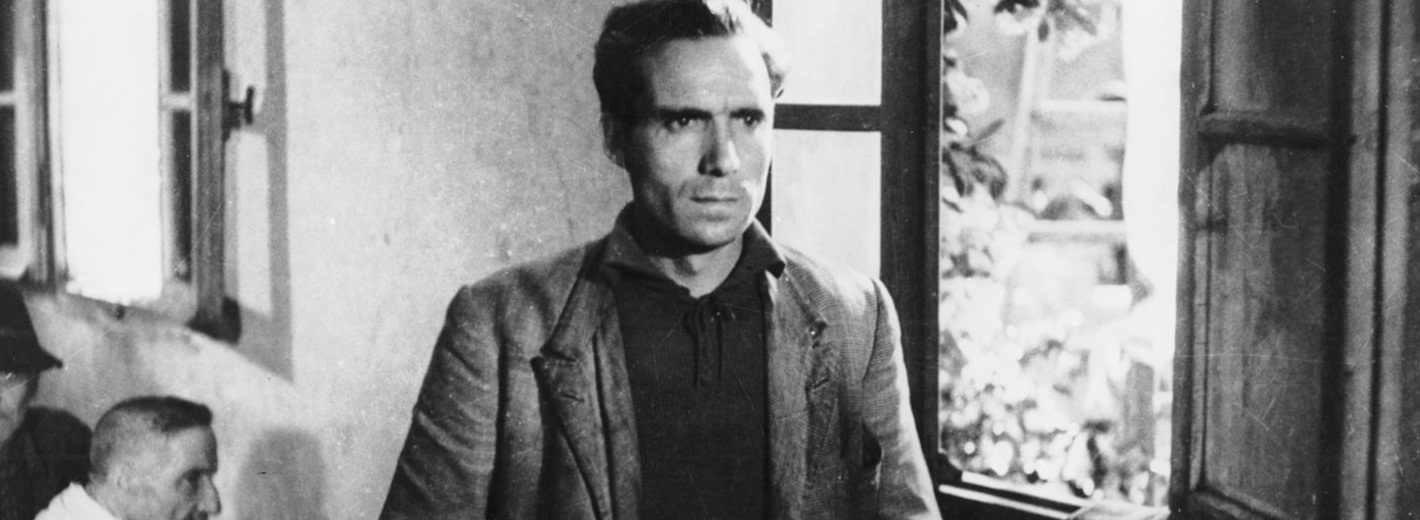

Broken Flowers isn't exactly a sexy subject for an article. In 2005, it came and went as a well received if unextravagant entry in the Jarmusch canon and another minimalist comedic melancholic performance by Bill Murray in the style of Lost in Translation. But the reason the film won me as its champion over five years ago is the same reason it fits together so nicely with The Bicycle Thief is the same reason it was dismissed by so many. This film is not about what you think its about.

Hitchcock called it a "macguffin." It's the plot device that exists to drive the film, but isn't really what the film is about. In The Bicycle Thief, that device is a bicycle stolen from Antonio, a poor man who needs it for work. In Broken Flowers it's a letter from an anonymous ex-lover of Don Johnston (Murray) claiming that he has a son. In both cases, this early development sets our protagonists out on an almost impossible odyssey to either find and retrieve the lost bicycle or find and reclaim the unknown child.

Long before modern independent filmmakers were finding influence from The Bicycle Thief (discussed last week), Jim Jarmusch was borrowing the realist aesthetic back in the 1980's as a great way to stylistically account for having little to no budget. It shouldn't be surprising that his films, which often feature social outcasts on a quest owe much to Vittorio De Sica and his neorealist contemporaries. Especially in Broken Flowers, because in both films the climax does not solve the problem or the "macguffin" put forth in the film's first act.

We don't know if Antonio will ever find his bike or if Don will ever find his son. It doesn't matter. The resolution of these mysteries are not the purpose of our films. The purpose is in the journey. Generally, more viewers seem to accept this in the older film, possibly because it's foreign or because those seeking it out have a greater understanding or expectation of its purpose then anything that must be marketed for modern audiences.

But it's not infrequent for this concept, the unresolved mystery to be met with shock. So it was in the 60's when a missing person in the Italian film L'Avventura went undiscovered. And so it was a few years ago when a showdown over a satchel of money in No Country for Old Men never came to fruition. The purpose is in the journey, not the payoff.

It may be too strained of a connection to suggest that both Antonio and Don's journeys are mid-life crusades to make something of themselves in the eyes of their progeny. But it's not too much to say that both missions end in abject failure, both take desperate men and hurl them deeper into desperation than they ever thought possible. Both films reveal to their protagonists truths that they failed to truly understand before: the importance of family, the dangers of vanity, and the interconnectedness of hope and pride.

What matters at the end of both films isn't whether their journeys have been worth taking, but how they have come to define these men's lives. Like last week, the resolution isn't particularly cheerful, but the humanity both filmmakers show toward their protagonists is palpable and the suggestion that even in middle age, a life can become redefined is powerful.

The saying "life's a journey, not a destination" is as cliched as they come. But perhaps we've not heard it enough if films with ambiguous or unresolved endings like these continue to inspire apathy or derision, or an inability to see the massively changing lives unfolding in front of us.