Michael C. here to try to look past the standard take on one of our leading filmmakers.

Steve Zissou: This is going to hurt.

I have decided that I am no longer interested in reading reviews of Wes Anderson films that contain the word “quirky” in the opening paragraph. Same goes for “twee”.

Over and over I read that, what do you know, Wes Anderson has gone and made another Wes Anderson movie. It’s about time, don’t you think, that people take a more substantive look at a one of the most distinctive bodies of work of the last two decades? A body of work whose deeper currents are often ignored amid the same old talk about flat compositions and diorama sets. Anderson’s movies have a lingering impact that defies those would dismiss his carefully composed world as emotionally detached. Right below that carefully composed surface are the deeper currents of a director preoccupied with death, loss, and alienation.

With all the focus on his signature colorful style are we ignoring Wes Anderson’s dark side?

In all his films there is a moment when the material takes a turn and what we took for a fun romp veers into painful territory. There is the gasp-inducing suicide attempt at the center of The Royal Tenenbaums, or the excruciating unbandaging of Owen Wilson in Darjeeling. The death by helicopter crash at the end of The Life Aquatic remains shocking all these repeat viewings later, and even a film as ostensibly fun as The Fantastic Mr. Fox has at its heart the title character’s existential crisis.

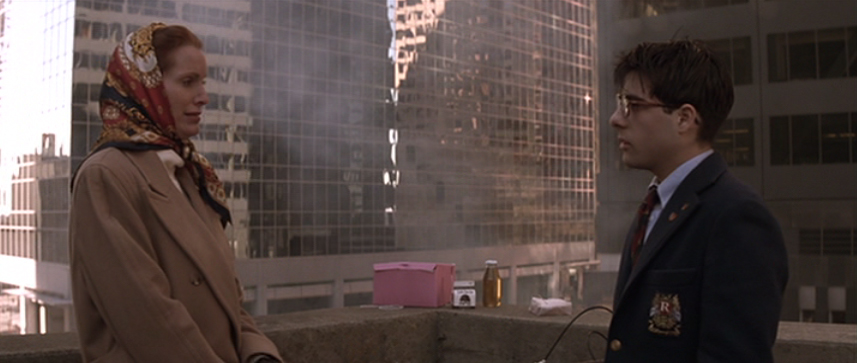

The scene that always sticks out strongest in my memory as encapsulating Anderson’s method is a moment about halfway through Rushmore. The feud between Max Fischer and Blume has been escalating just as we would expect it to in a light-hearted comedy starring Bill Murray, when Max invites Mrs. Blume to a secret meeting in order to spill the beans about Blume’s infidelity. It’s a jarring, uncomfortable scene. The actress portraying Mrs. Blume plays it absolutely straight and Anderson acknowledges the break in tone by having Mrs. Blume dismiss Max’s comical offers of premade sandwiches with a sad “Get to the point”. As for many, Rushmore was my first exposure to Anderson's world and I can recall realizing “Oh, this movie isn’t playing around.” Now that I’ve becoming familiar with the directors work over the years I can see clearly how the whole film is colored with loss from Max’s mother to Mrs. Cross’s lost husband to Blume’s distaste for his own family. For all his arch stylistic touches Wes always takes the pain of his characters seriously.

I can hear Anderson’s detractors sniffing derisively. For those who never managed to get on the filmmaker’s wavelength his weightier moments are just another in a series of affected poses. To them he is like the teenager who is suddenly very into the works of Sylvia Plath, wrapping himself in the subject of death as a none-too-subtle attempt to produce the illusion of depth and wisdom. The fact that he dresses in dapper Mr. Fox clothes like he is auditioning for one of his own movies, does not help him to be taken seriously.

I would counter that just as we readily accept comic relief in a heavy film, so too can a seemingly whimsical film contain moments of complete seriousness. That if a director is skilled enough he can maintain his tone while challenging the audience’s expectations of what kind of film they are watching. And that despite the apparent opinions of the modern movie going masses total realism isn’t the only vehicle for dramatic material.

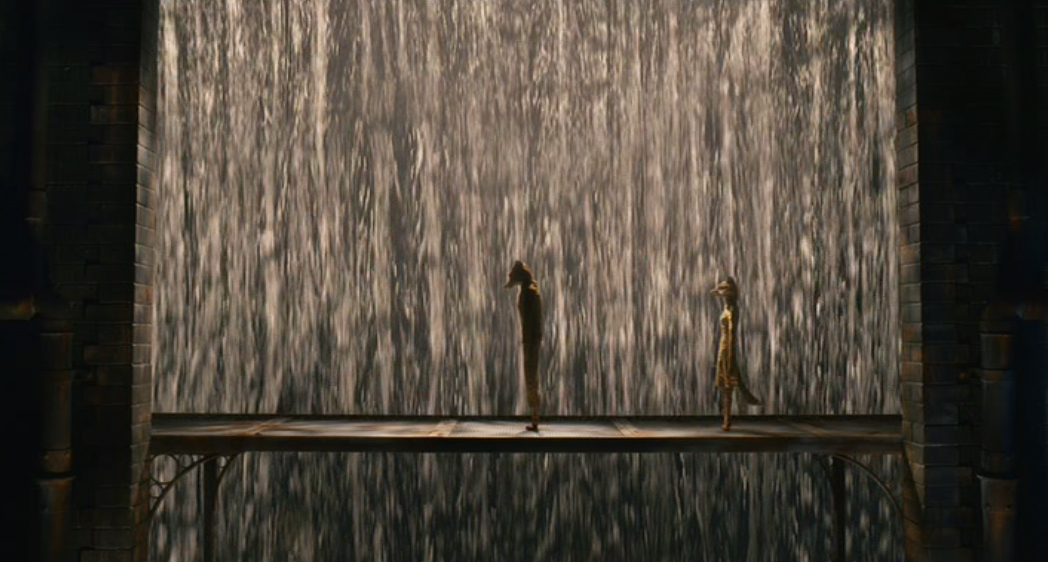

Moonrise Kingdom (2012)

Moonrise Kingdom (2012)

And now with Moonrise Kingdom Anderson has released his what appears to be one of his lightest films yet. Young people in love stealing away from their dysfunctional homes for a few days of undisturbed happiness on an impossibly charming island town, complete with Ed Norton done up as an overgrown boy scout. And it is that movie, but even Moonrise's moments of utter joy, like the young couple’s glorious dance on the beach, come tinged with the knowledge that their time is fleeting and adult complexity threatens their hideaway paradise from all sides and from within their own swirling emotions. The darkness is always present in Wes Anderson’s world. That he can acknowledge it while still seeing the possibility of warmth, humor and even healing is the reason so many like myself find his world a place we so often want to visit.

Your turn.

Is Wes the hipster-poser his haters say he is? Do critical circles acknowledge his place in the top tier of working directors? You can follow Michael C. on Twitter at @SeriousFilm or read his blog Serious Film.