Hello Readers!

Beau here, detailing my experiences with David Cronenberg's polarizing new feature, Cosmopolis.

Let's jump right in.

Cosmopolis, for better or worse, is David Cronenberg’s most interesting film since ‘A History of Violence’. I’d go so far as to say it’s his most interesting film that I’ve seen outside of ‘The Fly’, which blended offbeat genre, macabre humor and mainstream sensibilities seamlessly.

Don DeLillo’s original source material, which received mixed reviews upon its publication in 2003, warrants some credit here. He paints a world vividly enough for Cronenberg to get a direct sense of what it is he’s trying to illustrate with subtle colors and invisible brushes. It’s too easy to say that Cosmopolis is strictly an indictment of the Capitalist regime that we’ve built up over the course of our existence as a relatively young country. It’s also too simple to call it a character study; that would indicate that we have something resembling a character at the forefront of the conversation. We don’t.

Cosmopolis, for me, is something more. And less.

There’s a segment here featuring Juliette Binoche as R. Patz’s (adequate as our anti-hero, Eric Packer) art dealer. She mentions a Rothko painting that she will have access to shortly, that he ‘always wanted a Rothko’. Packer then inquires about the Rothko Temple, a non-denominational center based in Houston, Texas that features fourteen black paintings, open to the general public. Binoche rejects the idea of anyone owning the Temple; ‘The temple belongs to humanity’, she says. But Packer insists, makes arguments for himself and less for her that it could be done. It could be possible. He could own something human. Would that give him some semblance of life?

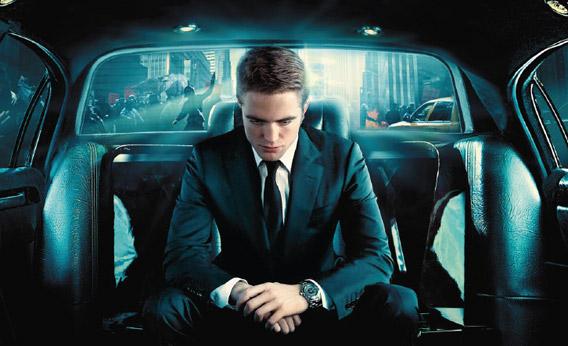

He’s like a fucked up corporate Pinocchio, if that’s the case. Watching ‘Cosmopolis’ is watching something entirely devoid of passion and life. That’s not a slight against the film, though I’m hardly inclined to label it a compliment. Theses and theoreticals delivered without slant, observations made clinical and curious about humanity, like it’s an abject sore; the world is open. Money has always been a barrier, to prevent the rich from touching the ground. It’s also a preventative measure, to keep Parker from directly feeling anything resembling emotion. These are hardly revelatory observations made about either the book or Cronenberg’s film. I’m aware of that. But approaching Cosmopolis in a critical sense is like approaching a man in a financial zoo, pin striped suit and dressed to the nines; you make observations about the man in the suit and you listen intently what he’s trying to say, but he can only speak in numbers. Which are universal, but void. You recognize similar behaviors, but you can’t wrap your head around the dissimilar ones. Watching Cosmopolis and Eric Packer the way that Cronenberg has directed is as clear and concise a study as any director could make; indeed, the film itself might be flawless.

But is that any indication of a good film? When one element is perfect, does the rest follows suit?

We watch Eric in the same manner he watches us. From a distance. We don’t understand him, and he doesn’t understand us. We both have barriers established; he, the bulletproof glass and the impenetrable walls of a white limo; us, the silver screen of our local cinema, our television, our iPhone. We regard the other as an artifact, curious relics from another place (and time). But isn’t Eric based in the here and now, alongside you and me? Isn’t he the chief target of Occupy? Isn’t he the asshole who wears sunglasses when he orders a latte and doesn’t deign to speak to or acknowledge you? Isn’t he the lack of humanity in humanity come to plastic, coded fruition? Is Cosmopolis then, a science fiction about the artifact of feeling? Something replaced by something else, something perfect, ‘the glow of cyber-capital’?

There is a distinct lack of humanity here, and there’s reason why. Cronenberg, cinema’s premier misanthrope (alongside Von Trier and, to a lesser extent, Haneke), is studying us through the veiled guise of the people he detests most. It is an observation through an observation of us that we’re observing. The sex here is passionless, the desire less to experience than to own, sensation enveloped and consumed by knowledge.

I don’t know what to think about this film. I don’t. I adore The Fly, I think History has its moments, Eastern Promises was a disappointment, and A Dangerous Method is as dull and lifeless a picture as any I’ve seen in years. But where this film differs from that one is that the clinical approach here is modernized, technology rather than sexuality the chief suspect of our absence. Which relies more on his strengths, in my opinion. Cronenberg is in search of where (and when) we lost our humanity. I don’t know where he’s looking next, but I anticipate it will be something equally ornate and opaque.

Never have I seen a film so completely and utterly realized and felt so little because of it. In that respect, David Cronenberg’s Cosmopolis may be a near-perfect picture.

It also might be a failure because of it.

Nothing human is perfect.