Hello, lovelies. Beau here, hoping you all have had a fantastic weekend. Whether that involved arguing over the season finale of Girls, shielding your eyes from Halle Berry’s hair in The Call, or just readying yourselves for the onslaught of leprechauns and green colored ale that is St. Patrick's Day, I hope it’s been an enjoyable one before heading back into the work week.

A lot has been said about Lena Dunham and Girls. I don’t have a strong desire at this point to rehash the plot details and synopses of the past episode or the entire season for that matter (though I did that for the finale of season one). But, for myself, being an avid viewer of Girls and eagerly anticipating the next step in Ms. Dunham’s career, the most discomforting element of all the criticism and controversy surrounding the show is that there is particular attention being paid to the characters "likability".

This concern isn’t strictly limited to Dunham or Girls. The "unlikable!" charge has been levied at multiple television programs and films these past couple of years, as though whether or not you liked the primary set of characters, or the supporting ones, dictated whether or not the work as a whole was working or not.

HUH?

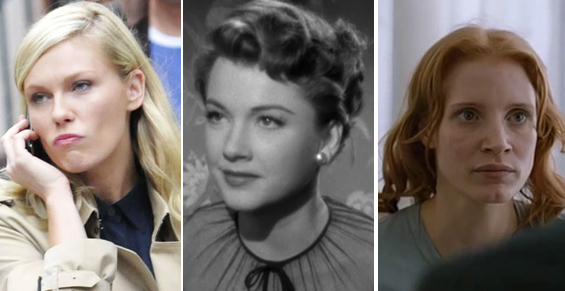

Regan. Eve. Maya.

Regan. Eve. Maya.

I remember being pretty put off, frankly, this past summer when several online pundits and reviewers were slandering Leslye Headland’s Bachelorette for this very reason. more...

As though it were a novel concept, to build a film around ‘unlikable’ characters whose self-loathing spills forth out onto one another, an addictive toxicity one could liken to a drug addiction or alcohol dependence. I liked these women because, guess what? They rang true. Self-destructive behavior can be a very difficult thing to watch, but what I found fascinating and commendable was the clarity with which Headland presented the women, not apologizing for who they are or allowing the characters themselves to apologize. Why should they?

The same kind of criticism was levied at Mark Boal’s drawing of Maya in Zero Dark Thirty, where we’re not given access to her life outside of her vocation. The script is purposefully dense in outlining her, save for a line about sex that’s pretty telling in and of itself, and the last silent moment where we see, in Chastain, a hollowness slowly being filled again. I wrote in my year end review of the best films of 2012 that the film is ‘fatalism on the rampage’. Maya is fated to this, not unlike Cassandra; it is her destiny. She believes that she is left alive when so many of her peers have been murdered or assassinated, because she is the only one that is meant to. That single minded determination does not allow room for you to carry your history, your fears, and your doubts; you are, simply, your mission. You are your destiny. Maya’s ultimate sacrifice is as valiant and honorable as any agent or officer she has served and lost throughout the film. But because we aren’t made privy to her life before her mission, we can’t account for her. How are we supposed to like someone we don’t know? the consensus rang. But how can we know her? Boal’s real achievement with this script was painting the reality that war is a monster that doesn’t take sides. It consumes everything. Unaffiliated Vampirism. The real tragedy of this, or any war for that matter, isn’t just limited to the lives lost on the field, but the lives of the men and women who had to lose themselves and come home afterwards.

See, it’s not as though we haven’t been inundated with flawed men and women and antiheroes for centuries. Hamlet, Macbeth, Nora, The Joker, Don Draper, Vanya, Anton Chigurh, Madame Bovary, Hedda Gabler, Miranda Priestly, Holden Caulfield, Annie Wilkes, Dexter, Tony Soprano, Cartman, Daniel Plainview, Walter White, Travis Bickle, Beatrix Kiddo, Shylock, Lisbeth Salander, Hannibal Lecter, and Scarlett O'Hara are all characters whose direct appeal is that they repulse us and entice us simultaneously.

But occasionally, we’ll be presented with wholly disgusting figures onscreen who are beyond our capacity for empathy. I think of Rachel McAdams in Midnight in Paris, a shrew of a woman conceptually conjoined with a shrill, vacant performance that does nothing to enhance or make up for what Woody Allen's creation lacks on the page. I think of Ellis on Smash, a character so driven by his ambition, so merciless and repulsive in his actions that you can’t even be bothered to love to hate him. (That in and of itself is a high wire act, a very treacherous one that can only a handful of performers can tread across with relative ease. Think Imelda Staunton in Order of the Phoenix, Anne Baxter in All About Eve, etc.) But the vitriol and the hate I felt towards Ellis is a unique, rare strand where I hoped against hope, much to my surprise and shame, that he would find himself the victim of some unspeakable yet appropriate accident, like getting squashed by the Green Goblin during a performance of Turn On The Dark.

Their ultimate crime, as Nathaniel pointed out to me when we were discussing this earlier, is that they are not interesting characters. That long previous list of iconic men and women who have dominated fiction for the past few hundred years have the indomitable ability to pull us into their drama because, on some conscious or subconscious level, we want to understand them. They possess some ineffable quality that is both distinctly human and inhuman.

Now, of course, some people just may not be interested in the three women in Bachelorette. Or Hannah and her compatriots in Girls. Or any one of those characters listed up above. Maybe their plight and predicament doesn’t hold any interest for you in the slightest. That is a valid feeling, and one that no one needs to defend or explain. But if a character fascinates you, if something draws you to them, be it their morality or lack thereof, liking them is redundant, and besides the point.

In the end, you find you’re too busy watching them to care.