[Editor's Note: You know "Denny" well from the comments section. Since he's a choreographer by trade, I asked him to sound off on Dance in film. Particularly on Chicago since its win was so strangely celebrated at this year's Oscars making the show a weird mix of 2012 & 2002. Take it away, Denny. - Nathaniel R.]

a happy night for CZJ & Friends, March 23rd, 2003

a happy night for CZJ & Friends, March 23rd, 2003

Oh, how I remember the cheers.

I was at an Oscar party with a group of theater friends ten years ago when Rob Marshall’s Chicago became the first musical in thirty-five years to win the Oscar for Best Picture. It’s easy to see why everyone was excited: Following Moulin Rouge! (and to a lesser extent, Hedwig and the Angry Inch) the year before, it was clear that Hollywood was finally interested in live-action musicals not aimed at children again. There hadn’t been a major live-action Hollywood musical aimed at adults since 1996’s divisive Evita, and before that the last one was 1986’s Little Shop of Horrors. The last to receive major awards attention was 1982’s Victor Victoria (or 1983’s Yentl, depending on your definition of “major awards attention”), and a musical hadn’t won the Oscar for Best Picture since 1968’s Oliver!, a much-derided winner in a year that actually saw two musicals nominated for Best Picture (the other being Funny Girl), if you can believe it. more...

Among the theater people I know, Chicago is still held up as a bit of a gold standard for filmed adaptations of stage musicals. Even though it takes place in the 1920s, the script’s cynical attitude couldn’t feel more modern, and the costumes, choreography, and camerawork combine to make it fresh ten years on. Compare it with the other movie musicals that won Best Picture (The Broadway Melody, An American in Paris, Gigi, West Side Story, My Fair Lady, The Sound of Music, and Oliver! – only the last four of which are adaptations of stage works) and it certainly stands out. Even in their best moments, none of these films come close to matching Chicago’s energy, its excitement – its “razzle dazzle”. This is a movie musical that knows how to put on a show of its own while still remaining pretty faithful to the source material.

Or at least, that’s what my friends responded to. I responded to the dancing. Having been a dancer since I was ten years old, I was finally starting to test the waters of actually creating dance – becoming a choreographer. Rob Marshall was a Tony-nominated choreographer before he took to directing, and his choreography in Chicago is pretty excellent. But that wasn’t what impressed me, exactly; I’d seen plenty of great choreography before, but this was different. It felt different. The opening number (the iconic “All That Jazz”) left my jaw on the floor, “Cell Block Tango” caused my eyes to practically pop out of their sockets, and by the time we got to “Roxie” I finally realized what made the dancing in Chicago feel so special: Marshall wasn’t just using the extra space working on a film gave him, he was using camerawork and editing to work with the music and choreography in a way few musicals had before.

Invitation to Dance

Invitation to Dance

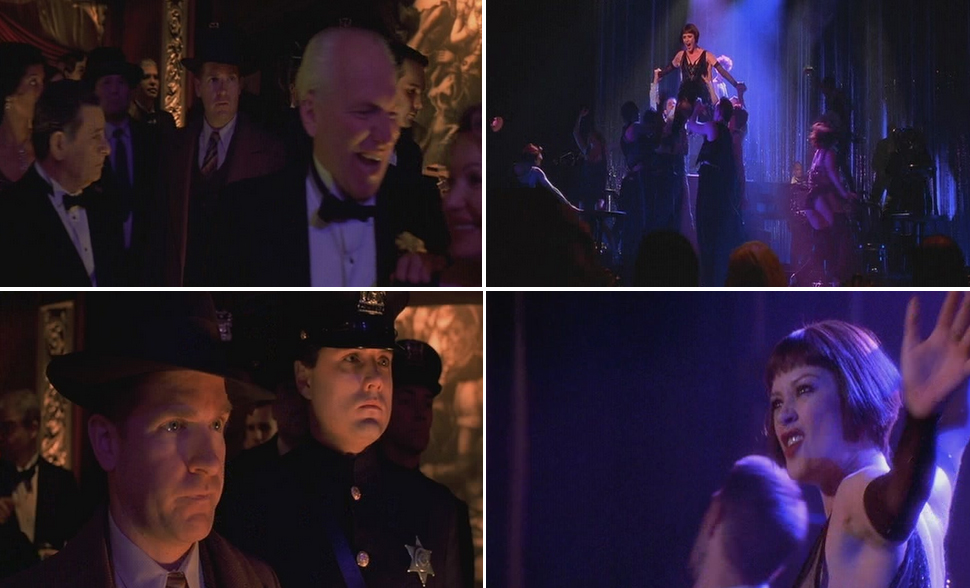

Choreographing for the camera, as I would later learn in my first choreography class, is its own skill set. Marshall proves he’s mastered it as early as Chicago’s first scene. In the stage version of Chicago, “All That Jazz” is basically an extension of the overture, an invitation to the world of the show, with no relation to the larger story. On film, it’s shown as the number Velma Kelly is performing the night she gets arrested, and adds a twist: In one of the swiftest examples of establishing a film’s visual signature in recent memory, the camera zooms in on Roxie as she hungrily watches Velma perform, and just when it can’t zoom any more or cut between the two of them any faster, Velma whips around to reveal Roxie in her place, singing the final word in the title phrase. Then, just as quickly as it happened, we’re out of Roxie’s fantasy back in the real world, as she leaves the club with her beau, Fred Casely.

From there, Editor Martin Walsh (a most deserved Oscar winner) intercuts Velma’s nightclub act with Roxie and Fred’s roll in the hay, images of entwining hands and loosening garter belts matching the choreography. Chicago’s greatest strength as a film is its editing, but it’s also one of the most divisive parts of the movie. I’ve heard it derogatorily likened to the style of music videos, but there hadn’t been an adaptation of a stage musical this kinetically shot and edited before (and arguably since). I know many people who dislike this style because it obscures the choreography. They aren’t wrong, but when it’s done well, as it is in Chicago, the editing actually enhances the choreography, matching the rhythms of the music and the choreography, allowing us to see (and hear) things in ways we couldn’t if a more straightforward style was used.

The choreography for “All That Jazz” starts out sexy and slinky, and our view is constantly obscured by patrons, chairs, and even the dancers’ own bodies, making the scene seem even seedier than it already is. Close-ups on feet, legs, and arms in motion fetishize every part of the performers’ bodies, moving just as fast and rhythmically as they do. Everything has a rhythm, interlocking with the music and the other movement on stage, and the camera captures this: a quick shot of a dancer fan-kicking her legs as she lays flat on a table follows it just as it fits the music. There is simply no way to recreate the feeling of that shot on stage – it’s shot from a higher angle than any seat in a theater, and the camera moves in such a way as to maximize the movement of the dancer. Not a single piece of choreography is wasted in this film; we get to see everything, even if it’s only a split second to punch a beat or out of focus in the background.

And Marshall never forgets that “All That Jazz” is a sister act turned into a solo act, with constant empty space on the stage where dancers are either non-existent or clearly improvising. There’s a feeling of something missing, even while it’s clear that Velma is a star you can’t take your eyes off of, whether or not she were sharing the stage with someone.

As the music grows in intensity, Roxie and Fred get more heated, and the choreography speeds up. The editing matches it step for step, even slowing down to just watch as everything grows quiet for second as Velma sinks into a circle of dancers. And then, just as Fred tells Roxie that she’s his little “shooting star” (hehe), the focus is all back on Velma to finish the number. Make no mistake: Velma’s the star here, and if the cops are going to come in (note how Velma makes her way to the front of the stage just as the cops enter the club in a matching shot) and arrest her, she’s going to give even them the best goddamn show they’ve ever seen.

Row 1: Proceed to the front of the stage; Row 2: Is this the show you came to see?

Row 1: Proceed to the front of the stage; Row 2: Is this the show you came to see?

And so is Rob Marshall. He’s a true showman using all the tools at his disposal to entertain his audience. And in so doing, he takes a stage musical with a very theatrical concept and translates it seamlessly to film. Chicago is a near-perfect match of material, director, style.

What’s your favorite number/performance in the film? Or, if you're not a fan, which of its Oscars most trouble you? Find a flask, we’re playing fast and loose in the comments!

75th Annual Oscars ~ 10th Anniversary Special

Road to Perdition & Posthumous Gold

Nicole Kidman on Her Best Actress Win

Joe Reid & Nick Davis on The Hours