Tim Brayton here again. With the cinephile world still reeling from the passing of irreplaceable film critic Roger Ebert a few days before, and The Iron Lady Margaret Thatcher’s death the same day sucking up every available scrap of oxygen in the news cycle, the loss of Annette Funicello on 4 April to the MS that had forced her into retirement over two decades ago was generally reported as a sort of afterthought. A sad thing, but not remotely surprising, and not of particular importance in the grand scheme of things.

Tim Brayton here again. With the cinephile world still reeling from the passing of irreplaceable film critic Roger Ebert a few days before, and The Iron Lady Margaret Thatcher’s death the same day sucking up every available scrap of oxygen in the news cycle, the loss of Annette Funicello on 4 April to the MS that had forced her into retirement over two decades ago was generally reported as a sort of afterthought. A sad thing, but not remotely surprising, and not of particular importance in the grand scheme of things.

While it is true that Funicello’s death doesn’t represent the end of an epoch in quite the same as Ebert’s, it’s still worth stopping and reflecting on her career and what it represents.

She was not a great actress, nor was she a timeless movie star; as attested to by her obituaries, the bigger part of her fame was appearing on The Mickey Mouse Club in the 1950s than the 17 feature films she made, and despite its iconic resonance to the Baby Boomers, The Mickey Mouse Club isn’t perhaps the most lasting legacy one could leave behind. It’s the other half of Funicello’s career that I’ve come to talk about, though...

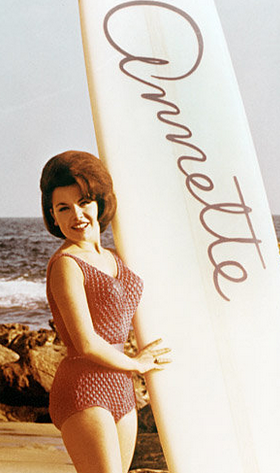

And while they’re ultimately just as ephemeral as any Disney-produced TV show for young consumers, the series of beach party movies produced by American International Pictures, starring Funicello alongside Frankie Avalon, are far more interesting and lively than their reputation as primitive teensploitation would suggest. 1963’s Beach Party and it’s half-dozen or so sequels and spin-offs (it depends on where, exactly, you set your criteria) are dated and frequently intolerably stupid, but they’re also among the weirdest mainstream movies that you could hope to find, all the weirder given that they were made by a company as wholly artless and mercenary as AIP.

Teen culture, as a marketing idea and a sociological force, is much newer than you might suppose: it effectively did not exist before World War II, and was formed throughout the second half of the ‘40s and first half of the ‘50s before it became anything like the dominant behemoth we know today (when “teen culture” and “pop culture” generally refer, functionally, to the same thing). The beach party movies were, therefore, not the first teen movies by any means, though they were the apex of that form as practiced by the studio that did more than anything else to solidify the idea of a teen-driven film marketplace. Even 50 years later, when their value to actual teens is somewhere south of nil, the beach cycle stands as being one of the high peaks of creativity in the teen film marketplace, marrying comic soap opera plots to fantasy and surrealism like nothing before or since.

Funicello’s role in all of that unreality was important and irreplaceable: she represented the films’ bedrock, their human anchor. Most of the beach party movies followed a specific formula, that gave most of the wackiest action to the side characters or antagonists, or even just to one-off figures who showed up to provide a random gag and then left; Avalon filled the time-honored role of the hapless boy who gets himself all tangled up in hijinx, to the amused exasperation of his best girl, who is plainly represented in all ways as far, far better than his charming incompetence deserves. It’s the template of all the most banal and anonymous TV sitcoms, but the beach movies, for the most part, make it work (though I should admit here, since I haven’t already, that I haven’t seen all of them), and a huge part of that is simply that Funicello and Avalon are delightful together.

Indeed, Funicello was a downright indispensable facet. She might not have been the reason for the films’ financial success (the audience being skewed female, it’s a fair bet that Avalon sold more tickets) nor their artistic leaps (William Asher, director of most of the movies, or Samuel Z. Arkoff, AIP’s impresario, certainly have more to do with that), but she was undoubtedly the glue of the movies, giving an entry point into the madcap nonsense that Avalon didn’t provide, and making them seem relatable and real. Not that she didn’t get to join in the shenanigans – Beach Blanket Bingo sees her going skydiving, for example – but she was the Everygirl that provided an identification point and a reason to care. And this was a role that Funicello played to perfection.

Decades later, we can look to her spiritual descendants, typified by Kristen Stewart’s Bella Swan in the Twilight pictures, with some dismay at how little connection to lived human behavior can be found there; and thus we can be all the more impressed by how great Funicello was at simply being a teenager. It’s surely not Funicello’s fault that so few of her successors lived up to her very appealing example, and her legacy isn’t just as a footnote in the history of how teen movies proved to be incredibly profitable, but as proof that, in the right hands and with the right faces, teen movies can be genuinely fun and lively. And that, I think, is a very fine legacy to leave behind.