Tim Brayton here, to talk to everybody about something particularly close to my heart, and particularly useless even in the grand scheme of cinema: the crushing lack of artistry and personality in American horror movies these days.

Tim Brayton here, to talk to everybody about something particularly close to my heart, and particularly useless even in the grand scheme of cinema: the crushing lack of artistry and personality in American horror movies these days.

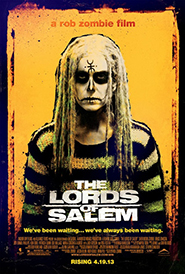

The issue is brought to mind by the release this week of The Lords of Salem, the fifth film directed by sometime heavy metal rocker Rob Zombie. I have not, at this writing, seen The Lords of Salem, and based on Zombie’s previous work, it’s very likely that I’m going to think it’s pretty terrible. But I am, anyway, more excited to see this than I have been for any other wide-release film in 2013, no matter how bad it’s going to be, because Zombie the filmmaker has consistently been responsible for horror films of the rarest sort: ones where you can actually tell how much the person making them cares about the work.

Since it became more or less socially acceptable at the dawn of the sound era, horror as a genre has never been overly concerned with artistry over commerce; even when it occasionally doubles as truly impressive cinema, whatever artistry a director like James Whale, David Cronenberg, or George A. Romero is able to bring to the table feels largely accidental. It’s still a form that caters to putting audiences in theater seats on the promise of exploitation and excess, secure in the knowledge that even a very bad movie isn’t very likely to hurt future business prospects, because the horror faithful are just going to keep lining up.

There are patches throughout history when a sustained run of genuinely good filmmaking in the horror genre can be found: Universal in the ‘30s, the early Gothics made by Hammer in the ‘50s and ‘60s. It’s never been the norm, though, at least not in English-language movies (Italy and Japan especially have strong histories of great horror). Even so, the 21st Century has been a particularly bad time to be a horror lover: between the garish geek shows of torture porn on the one hand, and anodyne PG-13 slasher movie knock-offs on the other, with the odd chintzy exorcism movie for flavoring, the last several years have witnessed some of the most soullessly mercenary horror ever made. And this brings us back to Mr. Zombie, who has been one of the solitary bright spots in a field of paint-by-numbers trash since his 2003 debut House of 1000 Corpses.

It’s certainly not the case that every one of his movies “works” – 1000 Corpses itself errs on the side of tedious fanboyism for the old school horror of Zombie’s imagination, and his Halloween II is an outright trainwreck – but every one of them is unique, and clearly the result of one man’s interests in terms of style (which tends towards the grungy brutality of ‘70s grind house films), and content (psychoanalytical pieces about the killers that, in other horror movies, would be anonymous murder machines). The Lords of Salem looks to be changing things up a bit, with a trailer suggesting the color-filled bravado of something like Dario Argento’s Suspiria, but both as a throwback to a classic form of horror, and a deliberate riposte to the generically gloomy haunted houses and the grainy found-footage cycle that has been sapping so much of horror cinema’s energy lately, the film is plainly coming from the mind of somebody who takes all of this stuff very seriously, and wants to spend plenty of energy and love into making something off the beaten track.

And that, in a nutshell, is why Rob Zombie matters; why he is one of the few auteurs in American film horror, even if right now he’s only gone 1-for-4 in his previous movies in my estimation. Simply put, he’s one of a very limited number of people making horror movies because they’re the kind of movie loves, and he wants to see more of them that are exactly the way he loves them. Offhand, I can’t name anybody other than Ti West whose work is as clearly and consistently the responsibility of a true enthusiast for the genre, and West is at times too involved in a generational love of irony to fully embrace the guts of horror the way that Zombie does. Even at their worst, his films still capture a feeling of danger and violent confusion, the feeling that genuine evil exists and can threaten us even in the audience.

No matter how messy or tacky or overwrought Zombie’s films can be, the one thing nobody can ever doubt is that he sincerely believes in everything he puts on screen. In a genre as prone to critical disapprobation and obvious cash-grabs as horror, that kind of sincerity is desperately welcome and needed in any guise it takes, and no matter how much his reach exceeds his grasp as a filmmaker, Rob Zombie’s movies are alive and engaged, and their vital sloppiness is worth far more than all these blank, repetitive poltergeists and watered-down remakes put together.