[Editor's Note: My apologies to Deborah Lipp (and you!) Since I forgot to post her review of her favorite Easter movie this weekend. Pretend it's still Easter for us! Here's Deborah to sing that movie's praises. - Nathaniel R]

[Editor's Note: My apologies to Deborah Lipp (and you!) Since I forgot to post her review of her favorite Easter movie this weekend. Pretend it's still Easter for us! Here's Deborah to sing that movie's praises. - Nathaniel R]

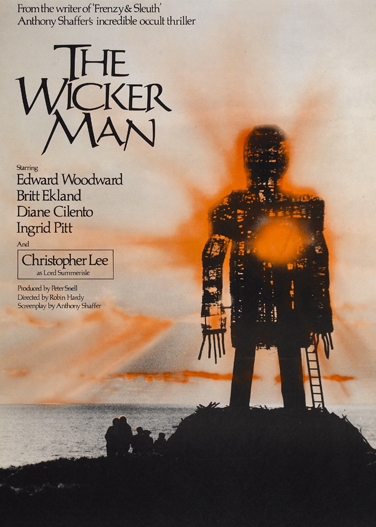

The Wicker Man is one of my favorite movies. There's a lot to be said about it, and I'm not going to say it all here. I'll start with the obvious: Different people perceive this film in very different ways. It's horror, it's a musical, it's kitsch, but it's also, quite blatantly, religious. Despite the fact that it takes place around the Pagan holiday of Beltane (May Day), I am going to argue that it's an Easter movie, dealing with sacrifice and resurrection.

May Morrison (to Sergeant Howie): You'll simply never understand the true nature of sacrifice.

The Wicker Man's horror centers on the conflict between two spiritual world views that are alien and opposite to one another. Sergeant Howie (Edward Woodward) is a pious, not to say priggish, Christian, while the residents of Summerisle are Pagan. (Spoilers aplenty once you proceed.)

(Parenthetically: There are modern Pagans who hate this movie, because of its depiction of malevolent, violent Pagans Yet Christians could as easily hate it for having prissy, officious, obtuse Howie as their representative. Best we all set the horror and villainy aside when looking at the religious aspects.)

Our protagonist, Sergeant Howie, a policeman who is a stickler for procedure, a Christian zealot, and a virgin, despite the efforts of his fiancé. He is contacted from the privately-owned island of Summerisle, famous for its apples, to investigate the disappearance of a young girl, Rowan Morrison. Upon arriving, he discovers to his horror that Summerisle has reverted to Pagan ways and the church has been entirely abandoned.

In The Wicker Man, we see a conflict between two very different theologies, although both are concerned with sacrifice and resurrection. Christians are shown to place spiritual value in separation from the body, while Pagans are depicted as having their spiritual essence rooted in nature and physicality. Sergeant Howie's religion is characterized by restraint and resistance; purity of spirit is attained by denying the body pleasure, especially sexual pleasure. Summerisle residents, though, find religion in sexual expression, nudity, and dance.

Sergeant Howie: What religion can they possibly be learning jumping over bonfires?

Lord Summerisle: Parthenogenesis.

Sergeant Howie: What?

Lord Summerisle: Literally, as Miss Rose would doubtless say in her assiduous way, reproduction without sexual union.

Sergeant Howie: Oh, what is all this? I mean, you've got fake biology, fake religion... Sir, have these children never heard of Jesus?

Lord Summerisle: Himself the son of a virgin, impregnated, I believe, by a ghost.

Sergeant Howie is lead to believe that the missing girl has been sacrificed, and, naturally, he is horrified by the notion, but the true horror awaiting him is that he, not Rowan Morrison, is the sacrifice. Despite how repulsed Howie is by Pagan sacrifice, his own religion venerates the sacrifice of a man: Jesus died for our sins, that we may live eternally. Sergeant Howie ultimately will die that the Summerisle residents might live: that their crops might succeed. Again, this can be seen as a conflict between spirit which is above, and separate from, the body, and spirit resident in the body and nature: Jesus sacrifices himself for our souls (above, separate), while Howie is sacrificed for something far more physical: Apples.

At one point, Lord Summerisle (Christopher Lee) brings a teenage boy—apparently a virgin—to Willow (Britt Ekland) to be deflowered, stating that this is a "sacrifice to Aphrodite," and that Willow is "the Goddess of Love in human form." Here it is again, sacrifice that is rooted in the body, in sex, and in pleasure. Later, Willow will attempt to seduce Howie and he will resist, holding firm to his faith. The seduction is an opportunity to save himself (he is a fit sacrifice, in part, because he is a virgin) and also an opportunity to convert; worshipping Aphrodite as young Ash Buchanan did. But Howie's faith is true and he will be martyred to it.

And be reborn, or so Lord Summerisle believes. Reborn as the crop, reborn as John Barleycorn. "Life of the fields. John Barleycorn," says the baker to Howie, as he pulls his bread from the oven. Just like that old Traffic song, "John Barleycorn Must Die"--the barley dies but is resurrected in the form of bread and whiskey. Sergeant Howie will die to be resurrected as apples, and he dies calling to Jesus, who was resurrected, not for human life, but for life eternal.

Sergeant Howie: I believe in the life eternal, as promised to us by our Lord, Jesus Christ. Lord Summerisle: That is good, for believing what you do, we confer upon you a rare gift, these days - a martyr's death.