Hi all, Tim here. Like a lot of you, I’ve been waiting on Baz Luhrmann’s brand-new, all-3D, all-CGI version of The Great Gatsby with a kind of curious dread, on the assumption that the no-doubt overwhelming style and glitz would leave F. Scott Fitzgerald’s excavation of the limits of American ingenuity and self-invention a little bit lost amidst all the eye candy. And this seems to have been exactly the case, sadly.

Hi all, Tim here. Like a lot of you, I’ve been waiting on Baz Luhrmann’s brand-new, all-3D, all-CGI version of The Great Gatsby with a kind of curious dread, on the assumption that the no-doubt overwhelming style and glitz would leave F. Scott Fitzgerald’s excavation of the limits of American ingenuity and self-invention a little bit lost amidst all the eye candy. And this seems to have been exactly the case, sadly.

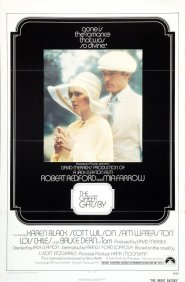

But let us not come down too hard on Baz. There’s also the possibility that Gatsby simply isn’t a novel that’s meant to be filmed, and as evidence I’d like to call upon the last feature film adaptation, and certainly the best known prior to now. Of course, I mean the 1974 Paramount production starring Robert Redford as Jay Gatsby, Mia Farrow as Daisy Buchanan, and Sam Waterston as Nick Carroway, and a general sense of lifeless ennui as the stimulus-crazed Roaring ‘20s. Other than a fixation on production design and costumes (it won the Oscar for the latter), there’s not much that the ’74 film has in common with Luhrmann’s screamingly excessive vision; if anything a bit more of a willingness to push against the book, rather than to so dutifully illustrate it in the driest way possible, might have benefited it. Movies are not books, after all, and this version of Gatsby badly loses sight of that truth.

Its overriding problem, even more than a desperately uneven cast, is a glassy-eyed literalism on the part of director Jack Clayton and the narration-heavy screenplay credited to Francis Ford Coppola (who flatly denied that the final version was based on his draft), less interested in exploring the pages of the book than unimaginatively reproducing them. Ironically, this means that the film completely misses the marks as an adaptation of Fitzgerald: stylistically, The Great Gatsby is famous for its efficiency and concision, painting entirely in short brush strokes that imply shapes without making anything needlessly overt. That results in a compact book that’s a swift read; but when it’s transliterated so dutifully to cinema, the result is the exact opposite: images lie there leadenly, as Waterston’s frequently redundant narration and Clayton’s static blocking of character scenes conspire to make every moment stretch out into oblivion. The book implies; the movie yells, and then yells a second time just to make sure we got it.

It’s attractive at least, and though the cinematography bears all the hallmarks of a 1974 production (browned-out colors, and zooms that exist solely to amuse themselves), at least Clayton and his DP, the ever-reliable Douglas Slocombe (later of the Indiana Jones movies), capture the exhaustively well-designed sets with a certain clarity of vision that does give the film an undeniable authenticity of place; as I am not 110 years old, I can’t swear that it looks exactly like the 1920s in Long Island, but it certainly looks like the place that Gatsby is meant to take place, even if some of its locations verge on the overwrought – the valley of ashes is presented less as a metaphor, more as an Eastern European war-zone. And we are brought into it effectively by the filmmakers, even though the act of bring us in is so exhaustive as to leave no space for drama or characters.

The characters… yes. About those actors, there’s no way around it: Redford and Farrow aren’t as good as they could have been. Farrow in particular suffers from a particularly bold and ineffective series of choices to play Daisy as an addle-headed ninny with a fluty voice (when she utters the famous line about Gatsby’s shirts, it sounds like Katherine Hepburn voicing a Disney princess), a propensity for staring, and absolutely no attention span from the very beginning, making her not at all a Fitzgeraldian emblem of the unattainable, but more of a dreadful bore, the sort you talk to just long enough to realize what a loud, self-involved flake she is before taking the first chance out of the conversation that presents itself. It’s hard to regard Jay Gatsby as a tragic figure for pining after her, or as anything but a masochist.

Redford himself is, if anything, worse; not in such a splashy way as Farrow, but the deeper into the movie we get, the more that his palpable unwillingness to play anything but the smiling matinee playboy gets in the way of the movie doing anything with its central figure (in his 1974 review of the film, Roger Ebert suggested that Redford and Bruce Dern, who plays Tom Buchanan, could have profitably switched roles; having read that, it’s impossible not to think of how much better Redford’s performance would have suited that arrangement). This Gatsby is already lumbering enough; it certainly doesn’t need Redford’s non-committal performance to make it shallow, as well.

Redford himself is, if anything, worse; not in such a splashy way as Farrow, but the deeper into the movie we get, the more that his palpable unwillingness to play anything but the smiling matinee playboy gets in the way of the movie doing anything with its central figure (in his 1974 review of the film, Roger Ebert suggested that Redford and Bruce Dern, who plays Tom Buchanan, could have profitably switched roles; having read that, it’s impossible not to think of how much better Redford’s performance would have suited that arrangement). This Gatsby is already lumbering enough; it certainly doesn’t need Redford’s non-committal performance to make it shallow, as well.

Weirdly, given how badly the leads misfire, most of the supporting cast acquits themselves well (though hampered, every one, by a tinny sound mix that makes everybody sound harsh); Waterston’s Nick in particular finds just the perfect register of being a half-sophisticated outsider, and the film’s next two biggest female parts, Tom’s mistress Myrtel Wilson and Daisy’s catty friend Jordan Baker, are excellently played by Karen Black and Lois Chiles, respectively, each of them using the same period trappings that imprison Farrow to find something real and lived-in about the women they’re playing. And so on and so forth, into the smallest roles. Cumulatively, they add enough vitality and humanity to The Great Gatsby that it doesn’t counteract the claustrophobic direction and aimless leads, but draw attention to just how much the movie is misfiring at its most important points. It’s the worst of both worlds.

I’m not going to make the claim that any of this is better or worse than Luhrmann’s overcaffeinated take on the material, just that it is, in and of itself, no tribute to the novel it so scrupulously embalms. We’ve now had a Gatsby that fails for being too earnest in its attempt to dramatize the book, and a Gatsby that fails for being too irrelevant and shallow (and a film noir Gatsby from 1949 – the mind reels), which pretty much covers all the bases, and maybe the lesson here is that not every prose masterpiece needs cinematic enshrinement. But I’m not holding my breath that anybody’s going to learn that lesson soon.