Welcome to "The Honoraries". We're celebrating the careers of the Honorary Oscar recipients of 2014 and the Jean Hersholt winner (Harry Belafonte). Here's longtime TFE reader and new contributor Teo Bugbee, whose work you might have read at The Daily Beast, on Belafonte's biggest film...

Even in the fantastic canon of classic Hollywood musicals, Carmen Jones is a standout. It’s got all the colors—Deluxe, not Technicolor, which as any John Waters fan will tell you is the real deal—it’s got the timeless score by Georges Bizet, but before we talk about the film itself, let’s take a minute to look at the backstory, if only because what was going on behind the scenes in Carmen Jones is at least as interesting as what made it on film.

Though he never really made particularly political films, director Otto Preminger was a modern man when it came to his politics, and he proposed the idea of adapting the Broadway smash Carmen Jones into a film as a means of showing off the black talent that he felt Hollywood was excluding. But despite Preminger’s substantial box office clout, no major studio wanted to take on a film with an all black cast. So Preminger took Carmen Jones to United Artists and set out making it basically as an independent film.

Harry Belafonte was brought on immediately as Joe, but Preminger took a longer time to find his star, testing a number of black actresses.

Lusty affairs and a singular film after the jump...

(Most excellently, Carmen was initially offered to Eartha Kitt, but because Eartha Kitt was a bad bitch she turned it down when she heard that her singing voice would be dubbed.)

When Preminger finally did settle on a star, he went with the Dorothy Dandridge, and much to the surprise of all involved, the two began a torrid affair on set that would last for several years. It ended poorly, and Dandridge would later say Preminger’s bad advice ruined her career, but damn if whatever they had going on in Carmen Jones wasn’t working.

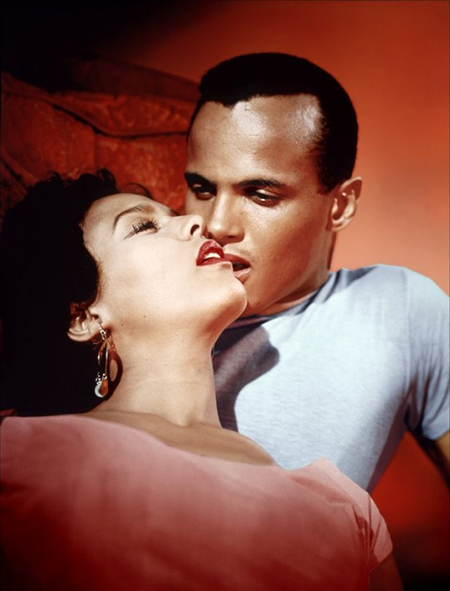

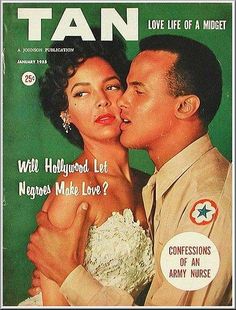

Like Bergman with Ullman, Fellini with Masina, in the sights of Preminger’s camera, Dandridge is radiant, and the camera trails her Carmen Jones at least as hungrily as Belafonte’s Joe does. Carmen Jones is a lustful film, and the frankness it displayed around sex and desire, especially with regards to black actors, was unheard of. It was banned in several states, and Preminger fought censorship from script to screen, and finally in the courts as he overturned the state censors in Kansas and Maryland in one of the first big blows to Hollywood’s production code.

But even knowing that, even now, the lustfulness of Carmen Jones comes as a surprise. It’s hard to remember the last time a pair of black actors got to make love on screen the way that Dandridge and Belafonte do, looking the way that Dandridge and Belafonte do. They are sexy, glamorous, and because Preminger favored long takes with such a wide shot scale, we have a chance to see them actually interact with each other in the same shot. They kiss, they touch, they’re physically intertwined as much as they ever are emotionally intertwined.

Carmen Jones was Preminger’s first musical, and frankly, at times the fit is a bit awkward. He favored an objective look at the world, and he liked to let his camera linger and wander, which means that sometimes the transitions into and out of songs are a bit abrupt, and the numbers rarely take hold the way they do in the hands of musical masters like Minnelli or Donen.

But looking at Dandridge and Belafonte, looking at the cast of entirely black faces, down to even the last extra, it’s hard to hold the occasional awkward moment against Preminger. The emotion in the film builds honestly and by the time the film reaches its tragic close, I always find myself a little stunned.

But looking at Dandridge and Belafonte, looking at the cast of entirely black faces, down to even the last extra, it’s hard to hold the occasional awkward moment against Preminger. The emotion in the film builds honestly and by the time the film reaches its tragic close, I always find myself a little stunned.

That’s it? There’s no more? Harry Belafonte didn’t go on to become the next Paul Newman, and Dorothy Dandridge didn’t follow in Ava Gardner’s footsteps? Why not??

And then of course I remember what industry I’m talking about. And I get grateful all over again for this film. When Oscar recognizes Harry Belafonte soon, it’s not just his humanitarian work they're honoring but the film he made, and all of the ones that he didn’t make. The ones Dorothy Dandridge didn’t make. The ones Eartha Kitt didn’t. And Sidney Poitier and Paul Robeson and Hattie McDaniel and Ruby Dee.

Carmen Jones might not have been able to open the gates for black American cinema, but it’s a window into that world that might have been. For that, and all other reasons, I’ll always love it.

Previously on The Honoraries:

Maureen O'Hara in The Parent Trap (1961)

Maureen O'Hara in Black Swan (1942)