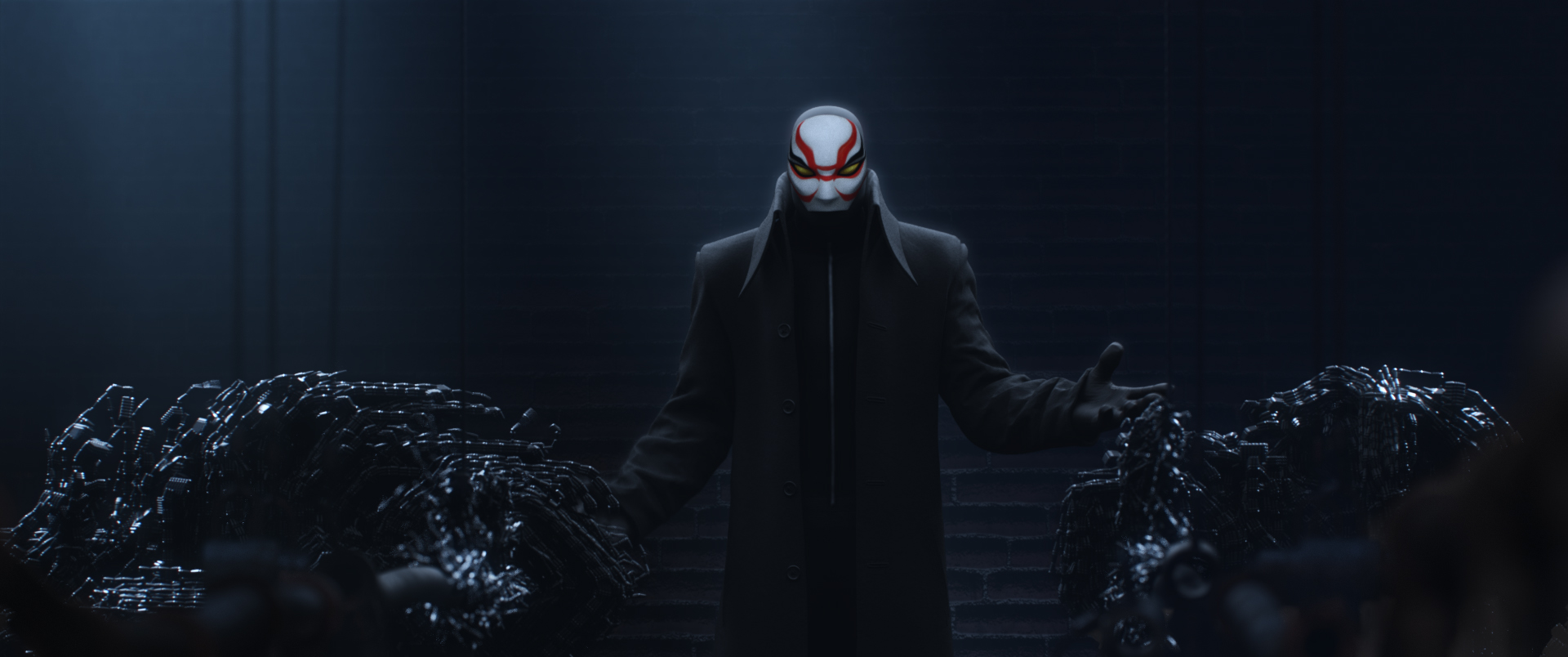

Tim here. Something feels unmissably “off” about Big Hero 6, the 54th film in the Walt Disney Animation feature canon. It’s a film that wants to offer a little something for everybody, and succeeds, but this comes at the cost of feeling erratic and imbalanced, and curiously adrift. By now, we’re used to superhero origin stories that use up all the oxygen on setting up the heroes’ powers and briefly sketching in their personalities, but even by that standard, as Big Hero 6 started to move into what was unmistakably its endgame, I found myself sinking into outright dismay that this inconsequential scrap against a nondescript bad guy with wicked plans barely large than a city block was actually where the movie was headed, after its strong opening.

Tim here. Something feels unmissably “off” about Big Hero 6, the 54th film in the Walt Disney Animation feature canon. It’s a film that wants to offer a little something for everybody, and succeeds, but this comes at the cost of feeling erratic and imbalanced, and curiously adrift. By now, we’re used to superhero origin stories that use up all the oxygen on setting up the heroes’ powers and briefly sketching in their personalities, but even by that standard, as Big Hero 6 started to move into what was unmistakably its endgame, I found myself sinking into outright dismay that this inconsequential scrap against a nondescript bad guy with wicked plans barely large than a city block was actually where the movie was headed, after its strong opening.

But that’s all part of the scheme: the filmmakers (including directors Don Hall, of the 2011 Winnie the Pooh) and Chris Williams, of 2008’s Bolt) know that some people want emotional tenderness, and some want big action scenes, and so they deliver both. But not in a way that’s completely satisfying to either group. It’s the same problem of every CGI animated American movie of the last decade and a half writ large and done with shockingly little attempt to disguise the joints between it narrative modules.

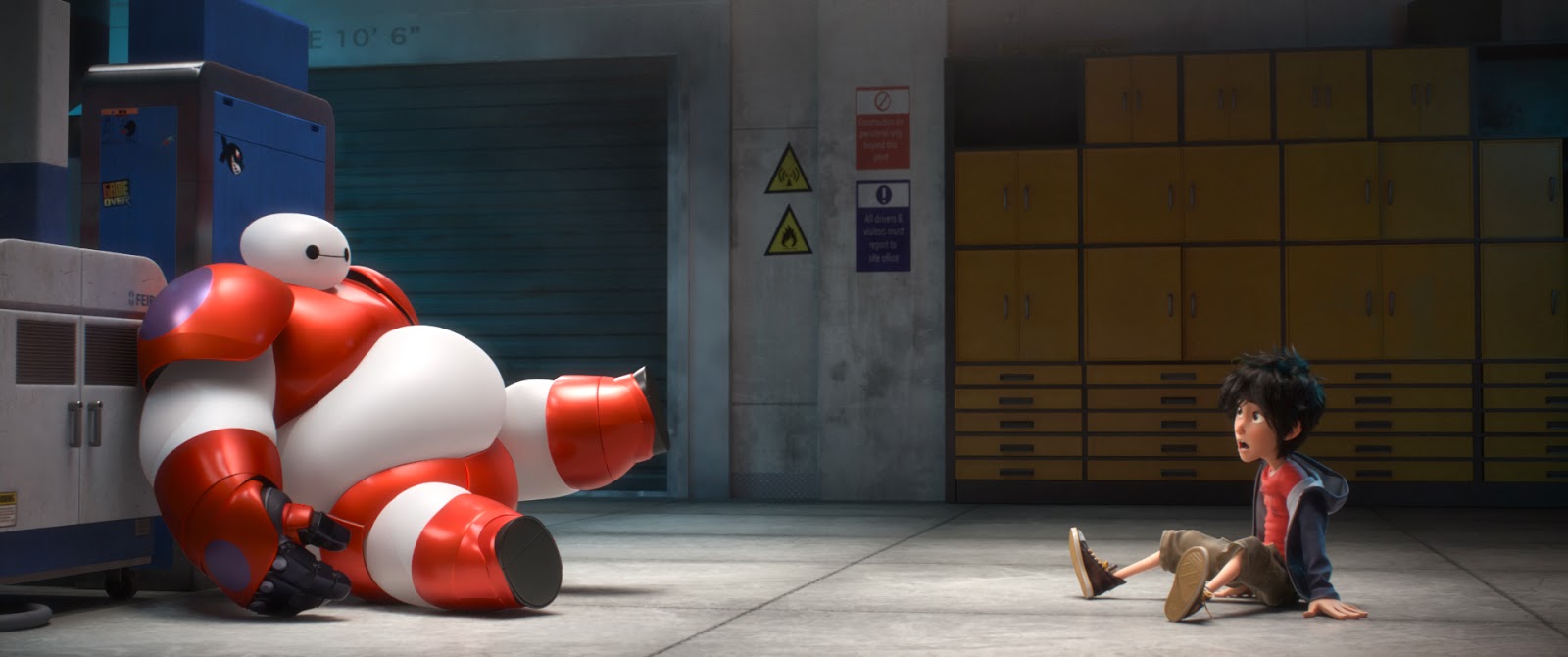

Bluntly, Big Hero 6 is a movie that feels heavily corporatized, from its concept on down. The film exists because some folks in the animation studio were prodded in the direction of pillaging the closets of their new corporate cousins at Marvel Entertainment, and found a five-issue comic book miniseries from 2008 that, according to legend, Marvel itself had completely forgotten about. This story, about a Japanese-based superhero team with strong ties to the X-Men (whose film writes aren’t held by Disney), was almost unrecognizably into the story of a teen boy, Hiro Hamada (Ryan Potter), bereaved twice over, who works out his emotional traumas through building wonderful robotics. And it is thus that he assembles, almost by accident, a group of himself, four of his older classmates at the local Generically Sciencey University, and the inflatable vinyl medical robot Baymax (Scott Adsit), who has dominated the film’s marketing and is easily its strongest individual component.

All of this is entirely fun to watch as it plays out: the other two-thirds of what will eventually be called Big Hero 6 are given nothing in the way of interiority, but they’re a well-mixed set of stock personalities from amiable laziness to brittle efficiency, and embodied by the most diverse cast Disney has ever assembled (two women, two men; only one white guy in the whole mix). The heart of the movie, in all senses, is centered on Hiro and Baymax and their pleasantly comic interaction – while there’s some roughed-up emotions centered on the relationship between brothers, it’s nothing remotely as complex as the sisterly core of Frozen – and that’s enough to keep the movie enjoyable, for the thing it is. Even the super-generic descent into superhero action in the last third isn’t bad. It’s just hollow and the stakes are totally unrelated to the family drama that opens things.

More than anything, Big Hero 6 is an overwhelmingly safe movie. It doesn’t merely subscribe to the story beats and friendly, obvious gags of animated family adventures, it typifies them: after a generation of Pixar copycats, I can’t think of anything that feels like it breaks away from the stock model less than this. That’s true of the storytelling, and it’s disappointingly true of the animation: Frozen was rightly dinged for effectively copying character models from Tangled, but at least it made up for it by including some detailed, innovative lighting effects and well-constructed snowy backdrops.

The designs of Big Hero 6 are a little more innovative than that, and Baymax’s flexible shape especially provides the animators with endless opportunities for squashing him around with all the slapstick brio of the more anarchic animation of the 1930s. But the film as a whole can only be thought of as a failure of visual imagination. It takes place in a hybrid called San Fransokyo, which in practice means slapping some Japanese design elements on a handful of buildings in a place that feels like the stock movie version of San Francisco. It’s fun, sure, and the colors are bright and eye-catching, especially once Big Hero 6 forms. But this is Disney, the company that once spent entire decades of its existence trying to push the medium forward. For it to produce a movie that’s this... normal looking is heartbreaking. There’s not much to actively dislike here, but there’s not a whole lot worth remembering, either, and the result is easily the most disposable film of the studio’s current neo-renaissance. B-