Tim here. With Black History Month still in full swing, I thought it would be worth spending some time diving into the history of African-American animation and reporting back to everyone with what I found, which turns out to be easier said than done. Despite a history of animation as an independent and avant-garde form welcoming any and all groups trapped without a voice in the mainstream reaching into the silent era, there has been shockingly little overlap between black cinema and animation down through the years. Which isn’t the same as saying that there’s none, and I am certain that there’s probably more than I was able to scrounge up over a couple of days of researching.

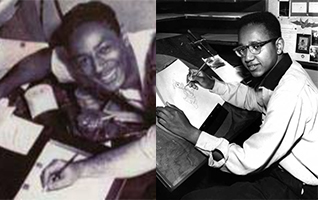

Pioneering animators Frank Braxton (L) and Floyd Norman (R)

Pioneering animators Frank Braxton (L) and Floyd Norman (R)

By and large, though African-American animators have been associated primarily with big studios, beginning in the 1950s, when Frank Braxton signed up with Warner Bros. By the end of that decade, Floyd Norman had become the first African-American employee of the Walt Disney Company, and his association with that studio continued well into the 2000s (and may continue yet – he’s still actively working, with a credit on a non-Disney production as recent as last fall’s dire Free Birds). The first significant branching out happened in the ‘60s, when Norman left Disney after its namesake and founder died, to join forces with new artist Leo Sullivan to create Vignette Films, a studio focused on making short animated explorations of African-American history (of any of these films still exist, the internet doesn’t seem interested in sharing them).

The breakthrough for Norman and Sullivan, and for animation by and about black people generally, when Bill Cosby tapped them to help develop a one-off TV special, Hey, Hey, Hey, It’s Fat Albert, a project very unlike the more famous TV series it spawned a couple of years later. It boasts a cruder, rougher, more aggressive style born from an urgent need to keep things as cheap as possible; by the same token, that rawness makes it much easier to appreciate the strength of the drawing, and the fluid casualness of the lines defining each character’s mood. Afrokids – the successor to Vignette films – has an absolutely essential gallery (warning: there’s an auto-play audio clip at that link) of test animation and drawings from the special, revealing an excellent, low-fi aesthetic that makes me positively sick to think that the special has been virtually invisible for over 40 years now.

Fat Albert opened the door for a wave of generally positive depictions of African-Americans in animation – a trend that reached its apotheosis in the magnificently ridiculous superhero cartoon The Super Globetrotters, which found the Harlem Globetrotters turned into the Fantastic Four – but not courtesy of African-American creators (even the ’69 special was directed by a white man, indie animator Ken Mundie), for the most part. It’s only been fairly recently that this has started to shift, largely thanks to television series like the Adult Swim series The Boondocks and Black Dynamite, or increasingly visible (but still rare) shorts every now and then.

To my mind, the most intoxicating and exciting work by a black filmmaker in animation lately, though has, been in an unclassifiable mix of live action, documentary, and indie romantic drama: An Oversimplifcation of Her Beauty, a 2012 film by Terence Nance that had the smallest of releases in 2013. It’s a complex and constantly-shifting analysis of the director’s perspective on his past relationships, with several of his exes revisited through mixed-media animated sequences. Messy and over-ambitious, it’s still leaves Nance as one of the strongest new voices in recent years, irrespective of race, genre, or medium. It’ entirely unfair to ask him to stand at the vanguard of any sort of new wave of black animation, but the fact he could make this film gives one hope for the future.

We are, at any rate, a long way from the barely-veiled minstrelsy of the early Looney Tunes, or the cringe-inducing likes of Bob Clampett’s notorious, well-intentioned, and horrifyingly racist Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs, as far as representation goes. Animated characters are still pretty damn lily white as a class, mind you, and it’s sort of jarring to realize that the first major studio animated feature directed by an African-American was Rise of the Guardians in 2012. But there are more minority voices in the industry with every passing year, and the possibility of a sustained, vibrant, and visible African-American presence in animation seems to be more a matter of when than if.