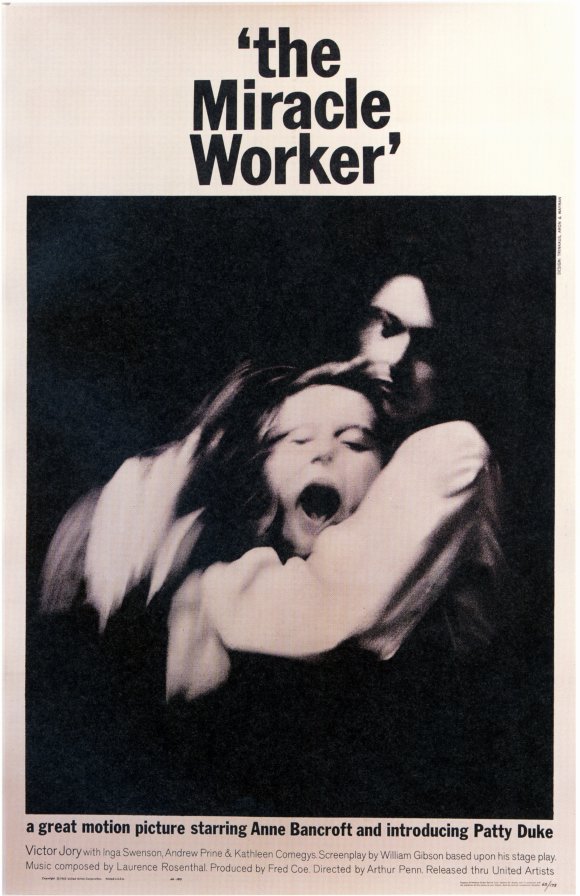

Our coverage of Women's History Month continues with abstew on "The Miracle Worker" (1962)

Born: Helen Adams Keller was actually born with the ability to see and hear on the day of her birth in June 27, 1880 in Tuscumbia, Alabama. It wasn't until she contracted an illness, most likely scarlet fever or meningitis, at the age of 19 months that she became both blind and deaf.

Johanna Mansfield Sullivan (she would always be known as Anne or Annie) was born April 14, 1866 in Massachusetts. After the death of her mother in 1874, Annie and her brother Jimmy were sent to an almshouse where she lived for 7 years. It was there, in 1880 (the year Helen was born) that she became blind after an untreated bacterial eye infection called trachoma.

Oscar winning performances after the jump...

Your Oscar Quartet from '62. Wait a second? Joan Crawford (who accepted for Bancroft) shoved herself in there?

Your Oscar Quartet from '62. Wait a second? Joan Crawford (who accepted for Bancroft) shoved herself in there?

Death: The women remained life-long companions. Annie Sullivan fell into a coma and dead on October 20, 1936 while holding Helen Keller's hand. Helen, who suffered a series of strokes in 1961, spent her remaining years at home where she died in her sleep on June 1, 1968. Both of their ashes are housed next to each other at the Washington National Cathedral in DC.

Their Extraordinary Lives: Wanting to find a way to better communicate with their daughter, Helen's parents were directed to the Perkins Institute for the Blind by telephone inventor, Alexander Graham Bell. Annie Sullivan, a graduate of the school was sent to teach Helen in 1887. Helen then went on to formal education at Perkins and other schools. In 1904, she graduated from Radcliffe College and became the first deaf blind person to ever receive a Bachelor of Arts degree. She became a prolific writer and lecturer (she learned to speak by placing her fingers on the lips, nose, and throat of people and repeating their sounds). She was also a vocal advocate for people with disabilities, a suffragist, a radical socialist, and an early supporter of birth control. Helen Keller was living proof that greatness can be achieved no matter what the circumstances.

Anne Bancroft and Patty Duke The Miracle Worker (1962)

Oscar Nominations Received by the Film: Reprising their roles from the Broadway production, the film won both of its leading ladies acting Oscars: Best Actress for Bancroft and Supporting Actress for Duke. The film was also nominated for Best Director (Arthur Penn), Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Costume Design (Black & White)

Oscar Nominations Received by the Film: Reprising their roles from the Broadway production, the film won both of its leading ladies acting Oscars: Best Actress for Bancroft and Supporting Actress for Duke. The film was also nominated for Best Director (Arthur Penn), Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Costume Design (Black & White)

The Other Best Actress Nominees: Bette Davis What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, Katharine Hepburn Long Day's Journey Into Night, Geraldine Page Sweet Bird of Youth, Lee Remick Days of Wine and Roses

The Other Best Supporting Actress Nominees: Mary Badham To Kill a Mockingbird, Shirley Knight Sweet Bird of Youth, Angela Landsbury The Manchurian Candidate, Thelma Ritter Birdman of Alcatraz

The film version of how deaf and blind Helen Keller began to effectively communicate thanks to the help of teacher Annie Sullivan seems like the perfect heartwarming tale for a Hallmark Hall of Fame film or a sappy after-school special. But Arthur Penn's 1962 film seems to be almost a horror story. In the first scene, Helen's mother (Inga Swenson) starts screaming bloody murder when she discovers that her baby has stopped responding to both sounds and visual stimulation. The opening credits then begin with surrealist black and white images that seem to come out of a nightmare (including a disturbing image in a Christmas ornament that shatters into a million pieces). Characters are not even able to find peace in slumber as Annie Sullivan is continuously haunted by her past and the death of her brother. And just look at that poster. Patty Duke resembles Edvard Munch's The Scream more than anything human.

The film is exhausting. Filled with a hyper energy (Victor Jory playing her father, seems to shout every single line. Helen might be deaf, but the audience isn't), the film propels the story forward through the sheer physicality of Duke and Bancroft's performances. Patty Duke throws herself into the role of Helen Keller–literally. (At 15, Duke was much older than the real-life Helen Keller was at the time and almost lost out on the part in the film. She was able to re-create her role after fellow Broadway co-star Bancroft was cast.) Playing Helen like a feral animal, Duke, her hair a tangled mess, covered in dirt, flings her entire body about with abandon. It's a fully committed performance that astonishes in its ferocity.

The centerpiece of the film is a throw-down, battle-of-wills fight in a dining room that is more relentless and raw in its violence than anything Quentin Tarantino could imagine. Helen, whose parents have allowed her to graze about the dinner table, shoves handfuls of food in her mouth and gobbles it up like a ravenous dog. Determined to make Helen a civilized member of society, Annie forces her to sit in a chair and eat with a real spoon. As Helen continually jumps up from the seat, she is forcibly thrown back down by Annie. The repetitive nature of it begins to resemble a Looney Tunes cartoon as Helen is unable to escape the determined grasp of her teacher–hopping up like a demented jackrabbit, only to be pulled back down firmly to earth. Like breaking in a wild horse, Helen eventually folds her napkin. A small step in her journey.

Bancroft's Annie Sullivan is out-spoken, determined, and a perfect foil to Duke's Helen. Never one to sugarcoat anything, her goal isn't to whip Helen into submission, but to unlock the power of language. She does it with grit and hard work. Bancroft's performance avoids cheap sentimentality. (Even stating that she's not even sure if she likes Helen.) Which makes Helen's breakthrough, realizing that each word that Annie teaches corresponds to an actual thing with the water from a pump, that much more emotional. We've earned this release.

Like Helen, we've awoken from the horror film:

To find hope in the darkness.

Related...

More Women's History Month

More on Oscars in the 1960s

More from Abstew