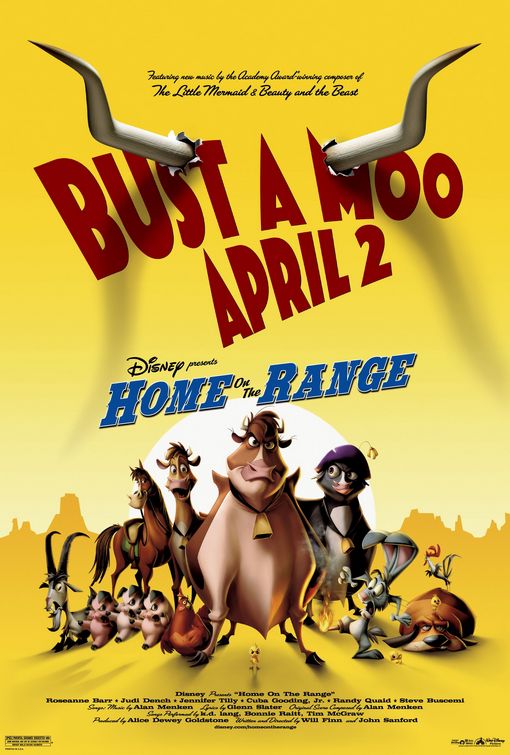

Tim here, to celebrate, and by “celebrate”, I mean “lament” the ten-year anniversary this month of the film that more or less killed traditional animation at Disney. Back in April, 2004, all that anybody could talk about was anything else imaginable other than Home on the Range, a Western comedy feature the voices of Roseanne, Judi Dench, and Jennifer Tilly that during its opening weekend only managed to scrape itself up to the #4 spot at the box office. This was to be expected. Disney had already announced prior to the release of Brother Bear the previous fall that once they cleared out the pipeline, they’d be abandoning 2D animation forever, and given the quality of most of their work in the 2000s, nobody could really be terribly offended by that decision for any strong reason other than nostalgia. Let me put it this way: I, in 2004, was easily the biggest Disney lover I knew. And even I didn’t bother watching it until a good year and a half later.

Tim here, to celebrate, and by “celebrate”, I mean “lament” the ten-year anniversary this month of the film that more or less killed traditional animation at Disney. Back in April, 2004, all that anybody could talk about was anything else imaginable other than Home on the Range, a Western comedy feature the voices of Roseanne, Judi Dench, and Jennifer Tilly that during its opening weekend only managed to scrape itself up to the #4 spot at the box office. This was to be expected. Disney had already announced prior to the release of Brother Bear the previous fall that once they cleared out the pipeline, they’d be abandoning 2D animation forever, and given the quality of most of their work in the 2000s, nobody could really be terribly offended by that decision for any strong reason other than nostalgia. Let me put it this way: I, in 2004, was easily the biggest Disney lover I knew. And even I didn’t bother watching it until a good year and a half later.

I would love nothing more than to say, at this point, “this was a terrible injustice done to a great movie, because…” and that’s really not accurate. Still, Home on the Range is certainly better than its still-unchanged reputation would have it; the fact that Disney’s very next film was the outright toxic Chicken Little certainly helps to make it look that much better, as does the 2009 release of The Princess and the Frog, which took away the pressure for the earlier film to be The Very Last Traditional Disney Film.

It’s a goofy lark with a collection of characters that don’t all feel like they belong in the same universe, let alone the same narrative (Roseanne’s snotty anachronisms and Cuba Gooding, Jr’s antics as a kung-fu addled horse especially jar with the jokey sweetness of most of the movie), so anyone seeking any kind of emotional gravitas had best keep looking. Like The Emperor’s New Groove, from earlier in the decade – a film that has been largely redeemed in the ensuing years thanks to an appreciative cult and the rise of Patrick Warburton as one of everybody’s favorite voice actors – Home on the Range is strictly an exercise in cartoon gags, frequently adopting very un-Disneylike tones in the pursuit of whatever absurd joke makes sense in the moment. This is all about silliness, from the random plotting (the entire story hinges on a rustler whose yodeling hypnotizes cattle), to the all-over-the-place dialogue, to the bright and flat aesthetic.

It’s this last part that actually serves to distinguish the film, and if there’s any strong argument to be made that it deserves better than it’s gotten in the last decade, that’s where the argument starts. Compared to many – most! – Disney films, Home on the Range is surprisingly unattractive; it’s also one of the most singular, unique visual experiments that studio has engaged in since the 1960s. It is, in essence, an attempt to marry the hugely non-realistic lines and flat surfaces of limited animation of the sort best exemplified by United Productions of America in the ‘50s with the fluidity, depth, and detail of Disney animation of the ‘90s.

It’s not an entirely successful experiment: in particular, the collision between the two-dimensional characters and the involving CG backgrounds made with Disney’s Deep Canvas technology is one that the film never comes remotely close to resolving.

That being said, it’s enough of a one-of-a-kind look, not just in Disney’s canon but in feature-length animation generally, that I couldn’t bear to give up the whole movie. It’s weird, but in a very determined way that suits the zany comedy just right. Almost every character in the film seems to be made up of straight lines and acute angles, which lends it a sense of quick sketches without the weight and body of so many animated figures, and that in turn gives it a frivolous lack of seriousness that most theatrical animation has lacked for hoard on a quarter of a century now.

The film’s look is more that of a TV cartoon or a comic strip than anything else, done with the technical control of Disney animators at the height of their power (if not their inspiration). It’s not great art, but it’s different enough from most of what had gone before it to be at least moderately interesting; given the almost complete absence of traditional cel-style animation in the decade since, it’s even more unique-looking now than it was when it was new. I would never try to proclaim that this deserves more attention than the great Disney musicals of the ‘90s, but it deserves more attention than none at all, as proof that even in its lowest hour, the apparatus of Disney animation was still trying to do new and interesting things with its medium.