Glenn here looking at a film from my homeland. As I sat watching David Michôd’s The Rover surrounded by a room of American film critics, I began to think about politically-motivated cinema and how it is perceived by audiences who do not have a distinct knowledge of the subject at hand. Like many “new waves” that come about (which is basically a fancy term for “look, we’re finally paying attention to you!”), these films are usually the result of angry artists using their form to critique a government or regime. Some do it with unmistakable blunt force, while others take the allegorical road. In the case of The Rover, it’s the latter. So as I sat then more-or-less engrossed (more on that in a little bit) and admiring what Michôd was saying about Australian geopolitics (intentional or otherwise), I couldn’t help but think that – quite frankly – a lot of people aren’t going to get it.

Glenn here looking at a film from my homeland. As I sat watching David Michôd’s The Rover surrounded by a room of American film critics, I began to think about politically-motivated cinema and how it is perceived by audiences who do not have a distinct knowledge of the subject at hand. Like many “new waves” that come about (which is basically a fancy term for “look, we’re finally paying attention to you!”), these films are usually the result of angry artists using their form to critique a government or regime. Some do it with unmistakable blunt force, while others take the allegorical road. In the case of The Rover, it’s the latter. So as I sat then more-or-less engrossed (more on that in a little bit) and admiring what Michôd was saying about Australian geopolitics (intentional or otherwise), I couldn’t help but think that – quite frankly – a lot of people aren’t going to get it.

People that I asked seemed to be aware that the film was working on a level higher than mere outback action fodder, but would be hard-pressed to explain what it was all about. I don’t blame them – I wouldn’t want to follow Australian politics either right now if I weren’t personally invested in it. It's truly depressing. Furthermore, it’s not like I can claim to know the impetus behind any number of film movements, political or not. However, with The Rover I think it’s a tougher case to decipher because Michôd and his collaborators have made a very sparse film. These thoughts I was having came about during one of The Rover’s quieter scenes, of which where are many. It's film that surely could have been wound tighter in the editing room (although the work of newcomer editor Peter Sciberras is still effective, especially in the film’s impactful and exciting opening act) and perhaps a little more forthcoming with its details, if only to allow the international audiences that it’s bound to attract after the Oscar-nominated Animal Kingdom more of an access to its themes.

Michôd, Pearce, & Pattinson on set of 'The Rover'

Michôd, Pearce, & Pattinson on set of 'The Rover'

I loved that way Michôd very casually introduced the setting – “Australia. Ten years after the collapse.” – and added layers of allegory on top of it. The way Australian money has become obsolete and been replaced by the almighty American dollar, referencing the way Australia is very quickly descending into an American model of hostile pro-capitalism. The way the land is representative of a society that has become too reliant on minerals and fossil fuels resulting in a dead and barren land. The way unemployment, lack of education, and massive homelessness will soon grip Australia thanks to a government that hates anybody who wasn’t born into wealth. Whether I am projecting onto it, who knows? But I see it, and like another recent Australian film, Greg McLean’s Wolf Creek 2, its themes are wrapped in a particularly grisly genre package.

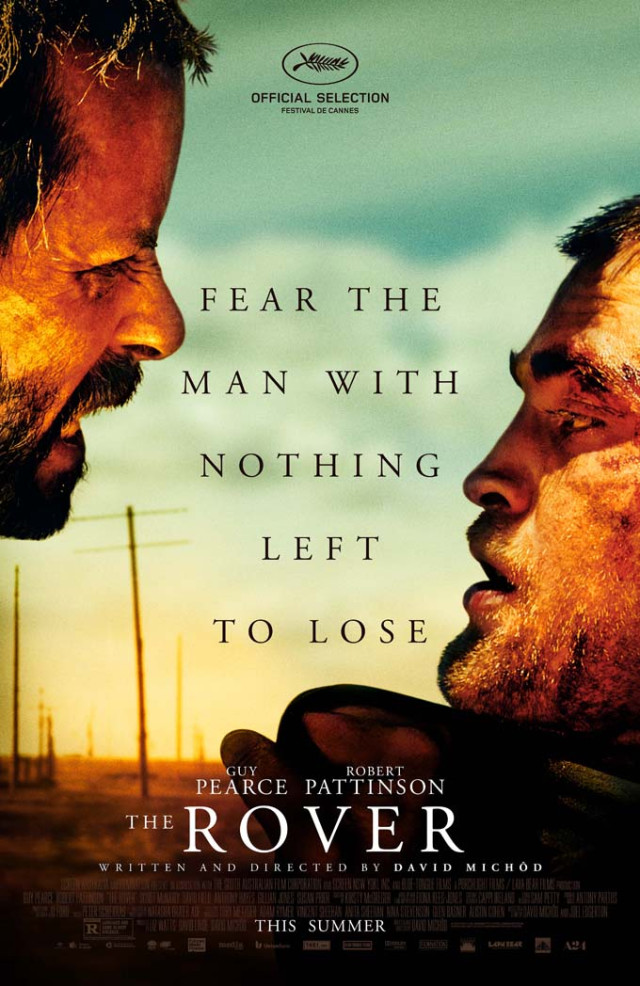

The story of The Rover is incredibly simple: Guy Pearce plays a seemingly nomadic man whose car is stolen by outback thieves (including Scoot McNairy). He sets out to retrieve it with the help of one of the thieves’ brothers, played by Robert Pattinson in a twitchy, very nearly overworked performance that eventually pays off in the final act. The film more or less plays out as a series of vignettes as the two men, covered in thick, patchy sweat and red desert dust, come across various outback dwellers including Gillian Jones (a brilliant Australian character actress) who is incredible in her brief role as a grandma that holds secrets and villainous dread in her nimble fingers. She and others like Susan Prior and Anthony Hayes give the film sparks of energy when Pearce is busy being stoic and silent, and Pattinson is mumbling into the dirt.

Gillian Jones in 'The Rover'

Gillian Jones in 'The Rover'

While The Rover lacks the narrative thrust of Animal Kingdom, it has potent things to say and allows Michôd to demonstrate a different set of filmmaking skills. Who would’ve guessed that he can film a car chase with such virility? And trading in the compact claustrophobia of the inner city for the vastness of the outback has allowed the director and his cinematographer Natasha Braier to craft some vivid, memorable images. I keep going back to that wonderfully orchestrated train sequence that so wonderfully utilises the widescreen, something that Braier also did so well in her work on The Milk of Sorrow. Or how about the shot, mere minutes into the film, where a car rolls silently by a large glass window as Pearce drinks at a bar blasting Japanese karaoke music. Genuine shot of the year contender right there, folks. And who would have thought Keri Hilson’s “Pretty Girl Rock” would make such a beautiful moment of bliss in a pseudo post-apocalyptic outback road movie?

The film's narrative sparseness surely dampens some of its drama, but in many ways it is a superior film to Animal Kingdom. It has more to say and says it in a more cinematic way. Many will hate it. I keep thinking of Andrew Dominik's Killing Them Softly in that regard. Even if all an audience sees is the story of a man and his rover, then there's much to admire.