[With Gay Pride festivities happening in various cities in June, we'll take a look back at a few gay classics. Here's Matthew Eng (who you'll remember from a couple of American Hustle pieces) on an Oscar nominated 80s classic - Editor]

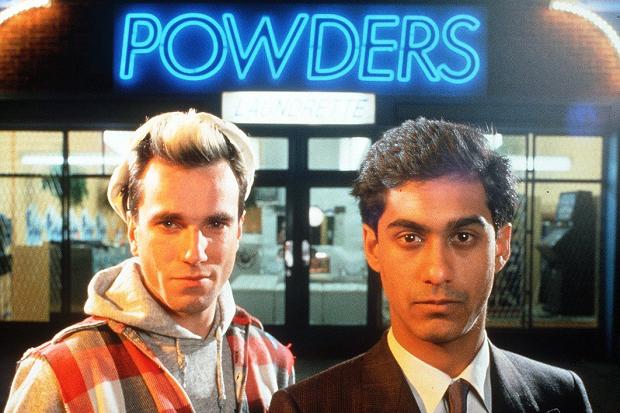

Initially envisioned as a low-budget, Channel 4 telefilm, My Beautiful Laundrette cheekily challenged the Western moviegoing market upon its U.K. and U.S. releases in, respectively, 1985 and ’86. It became an out-of-nowhere arthouse hit, all while ironically embracing and blending a distinctive, regional-specific grouping of Thatcher-era South Londoners who fall under social categorizations normally left discrete or disregarded in modern-day moviemaking, both then and now. In the film, Omar (Gordon Warnecke), a young, business-minded Pakistani-Brit, sets out to renovate his uncle’s dreary laundrette into a clothes-cleaning arcade, a luxury laundrette “as big as the Ritz.” To do this, Omar recruits Johnny, his white former classmate and one-time lover, resulting in all the charged, complicated power shifts that would inevitably stem from a South Asian British man employing his former skinhead ex-boyfriend in Thatcherite England.

Arguably the film’s greatest claim to fame is that the smirking, blonde-streaked, and neck-licking Johnny is played by an effortlessly charismatic and impossibly hot Daniel Day-Lewis, the only actor in the cast since allowed to top his work here (not to mention the only one still working, period) and whose strong turn in Laundrette—coupled with his amusingly meek snob in the same year’s Merchant-Ivory export A Room with a View—prompted a prize-winning stateside breakout...

Laundrette was directed by a then-unknown Stephen Frears, working in an altogether (and personally more preferable) register than something like the empty stateliness of The Queen or the tonally-fuzzy Philomena. I enjoy the devious, sumptuous Epicureanism of the Marquise de Merteuil and the desperate, chunky-sunglasses survivalism of Lilly Dillon as much as any self-respecting actressexual, but there’s something downright delightful about the modest, shoestring-quality of Laundrette, which never compromises style, wit, or sophistication in its quirky, confident execution, that continues to make it unquestionably my favorite Frears.

The script, by the enduring and politically mindful scribe Hanif Kureishi, remains a bold and appropriately eccentric blend of the personal and political, the aloof and the affectionate. It quickly became the film’s raison d’être, earning an Original Screenplay Oscar nom, but ultimately losing to the precarious Chekhovian predicaments of Woody’s Hannah and Her Sisters, which… fair enough.

Laundrette immerses its audience within a particular time and place of unique and unmistakable urban squalor, albeit without the miserabilism or moralism that often tends to penetrate much more self-admittedly social movies than this. It’s a film that takes a subversive look at the civic unrest engendered by Thatcherism not by placing itself within the hallowed halls of Parliament or amid all the familiar sights and sounds of Landmark London. Rather, the film sets its focus squarely on the people and places within its localized, South London setting. Laundrette evokes entire economic, political, and societal landscapes of sexual, racial, familial, generational, and environmental components (as well as all the intersectional overlap that occur amongst all of these) within the interiors of its characters’ world—the cramped apartments and spacious two-stories that are their permanent and temporary homes, their makeshift bedrooms and multiple workplaces (which sometimes serve the same function, as in the film’s deservedly-famous sex scene), the cobwebby, sparsely-patronized taverns with their shabby lighting and empty dance floors—as well as the complex signification that each setting maintains in relation to the others.

Upon my initial viewing of Laundrette roughly a year ago, I was left utterly (and not exaggeratedly) breath-taken by two key moments. The first is a fluid single shot that lifts us up and away from a moment of rekindled passion between Johnny and Omar within an alleyway at night and onto the nearby laundrette being vandalized around the corner by Johnny’s racist buddies. The second is that evocative, aforementioned sex scene, in which Johnny and Omar carry on in the back of the laundrette before its grand opening as Omar’s uncle and his white mistress dance to a swelling, synthy waltz in the front, a sight we glimpse through the slatted blinds during Johnny and Omar’s sweaty, champagne-swilling backroom encounter.

I am still just as captivated by these moments, even upon multiple repeat viewings, in a way that other much more romantic depictions of homosexual desire fail to excite me. Is it because Laundrette’s emphasis on non-overt sexual preferences refuses to linger in luridness and remains uncommonly advanced in its straightforwardness, even after nearly thirty years, when plenty of knowingly “gay” movies with even half that age tend to reek of musty, self-congratulatory tolerance? Johnny and Omar’s homosexual relationship is often kept in the dark, literally. It exists and is enacted upon first within the nighttime shadows of the alleyway, then later behind the closed doors and within the dimly-lit back rooms of a space that they own and (re-) built, but it isn't necessarily dramatized or “diagnosed."

I am still just as captivated by these moments, even upon multiple repeat viewings, in a way that other much more romantic depictions of homosexual desire fail to excite me. Is it because Laundrette’s emphasis on non-overt sexual preferences refuses to linger in luridness and remains uncommonly advanced in its straightforwardness, even after nearly thirty years, when plenty of knowingly “gay” movies with even half that age tend to reek of musty, self-congratulatory tolerance? Johnny and Omar’s homosexual relationship is often kept in the dark, literally. It exists and is enacted upon first within the nighttime shadows of the alleyway, then later behind the closed doors and within the dimly-lit back rooms of a space that they own and (re-) built, but it isn't necessarily dramatized or “diagnosed."

Johnny and Omar are far from being Tragic Gays, nor are they Cinematic Soul Mates; their devotion to one another is at times truly tender, but also just as often icy, cruel, and unsteady. And although both frequently function as fleshed-out rhetorical figures refracted through epochal political purviews, it wouldn’t be right to call either of them political characters, much less “advocates.” Instead, Johnny and Omar function as something else entirely: two gainful young men whose relation to self-advancement stretches as far as their own uncertain but committed form of couplehood, who each acquire the ability and ambition to gamble on their financial futures and in doing so, find a way in which they can also fortify their shared personal futures as well. It’s a depiction of queer identity that manages to somehow be both softhearted and unsentimental.

Despite its surprisingly long staying power, Laundrette isn’t a perfect movie per se. Kureishi cheats just a bit in ways that betray the film’s televisual roots, overstating plenty of political gags and drawing some secondary characters much too broadly, while shortcutting their arcs. The worst casualty is Tania (Rita Wolf), Omar’s headstrong cousin and sort-of fiancée, whose feminist rebellion against her family’s flawed sense of patriarchy never resonates in the same way that Omar’s or Johnny’s does. And yes, a few performances come off a little creaky, and nobody, save for (surprise!) the clever, impish, and moving Day-Lewis, escapes without a wooden line reading or three. But even the odd shortcoming is easily overlookable, especially since My Beautiful Laundrette still remains the cheeky and charmingly subversive entertainment it’s always been, a sly and subtly sincere touchstone of LGBT cinema, one with its tongue in its cheek but its head and its heart in the right place.