Episode 27 of 52: In which Kate goes to Africa with Bogart, Bacall, and Huston, and almost loses her mind.

When Katharine Hepburn decides to make a change in her career, she does not screw around. Kate’s first film of the 1950s (after a year off doing Shakespeare) was directed by John Huston, was shot in Technicolor by Jack Cardiff on location in Africa, and costarred Humphrey Bogart. When it opened in 1951, The African Queen was a hit, and eventually scored four Academy Award nominations (only Bogie won).

When Katharine Hepburn decides to make a change in her career, she does not screw around. Kate’s first film of the 1950s (after a year off doing Shakespeare) was directed by John Huston, was shot in Technicolor by Jack Cardiff on location in Africa, and costarred Humphrey Bogart. When it opened in 1951, The African Queen was a hit, and eventually scored four Academy Award nominations (only Bogie won).

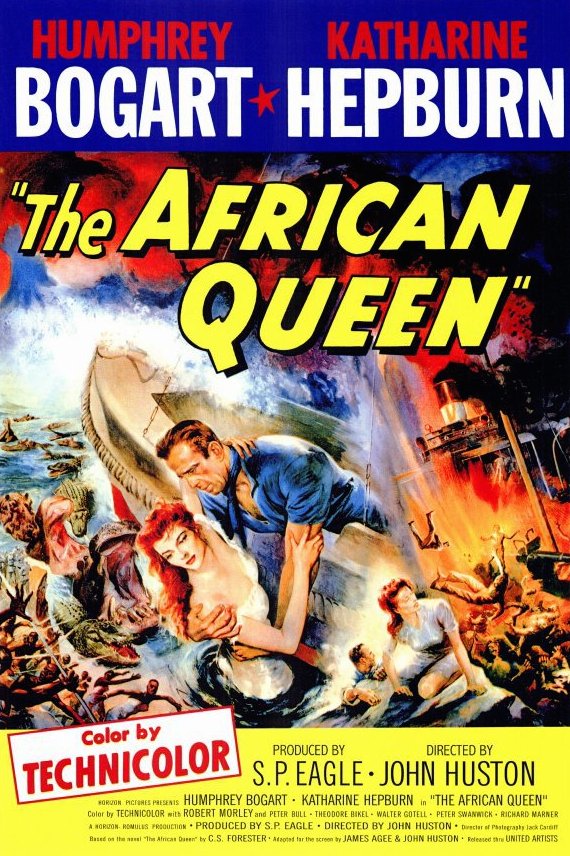

The story of making The African Queen is as incredible as the film itself. Everyone involved almost died at least once. Kate wrote a book on it (add author to her list of accomplishments), and it’s a fantastic read. Relevant to our interests is the fact that Kate got dysentery and dropped 20 pounds, making her already willowy frame even skinnier, a fact that would not be readily guessed from the promotional art:

"One of these things is not like the other..."

"One of these things is not like the other..."

Bogie’s got biceps! Kate’s got curves! What the hell? This has got to be my favorite example of misleading poster art, and not just because Kate looks hilariously like Rita Hayworth. This poster displays the conflicting image shift that happened for Kate in the early 1950s. The African Queen is the film that launched the spinster phase of Kate’s career. But though romantic glamor was a thing of the past image-wise, romance--specifically sex--would become even more important.

One sentence plot summary: A theologian thrillseeker and a half-cocked Canadian captain run a rustbucket boat down a river in the Congo to bomb the German navy in WWI. Sex and danger after the jump.

Early in the film, Rose Sayer (our own Kate) declares to Charlie (Bogart) that, “Nature, Mr. Allnut, is what we are put in this world to rise above.” This turns out to be an epic understatement. Neither the Germans nor the Africans (who are given less screentime than the crocodiles) are the villains of the film. Instead, Rose and Charlie fight the river and everything it throws at them--leeches, rapids, mosquitoes, leeches, waterfalls, fever, crocodiles, LEECHES. (The leeches bear repeating.) This is a survival action film, and like the best of that genre the trials the characters go through change them profoundly.

Rose Sayer is the first truly layered character Kate has played in a while. Rose begins the film as a steel-spined, well-mannered spinster. On John Huston’s direction, Kate plays Rose with a “society smile,” a thin-lipped grimace that she stretches towards the uncouth Charlie Allnut that reads as ingrained politeness, intense discomfort, and withering disdain. However, each new challenge from the river strips Rose (literally and figuratively) of her society trappings, revealing warmth and passion underneath. (The poor woman loses more clothing than Gypsy Rose Lee). Rose’s first revelatory moment happens after her first trip down the rapids:

Rosie looks like she just sat on a washing machine during spin cycle. The movie isn’t overtly sexual, but Rosie's big moments are always preceded by danger and sex. First this scene, when Rosie feels “stimulated” when she should feel terrified. Later, after escaping German gunfire, she and Charlie share a kiss tha leads to a sweet scene and a fade to black (wink wink nudge nudge) that consummates their budding relationship. These are fairly subtle moments that get swallowed by the showier dangers, but they set a precedent for Kate’s Spinster phase: what we’ll call the Character Development Deflowering. It will only get less subtle from here.

Like Rosie Sayer, Kate was a survivor. As shaky in quality as Kate’s 1940’s filmography had been, it proved one thing: there might be a Katharine Hepburn type, but there is no Katharine Hepburn genre. As the 1950s loomed and her image shifted from Desirable Star to Asexual Spinster, she still ran the gamut of genre, but with better films. The African Queen was Kate’s first Oscar nomination in almost a decade. By the time the 1950s ended and her spinster phase was done, she’d have three nominations more. That's one hell of a career change.

Next Week: Pat and Mike (1952) - In which Katharine Hepburn proves hitting like a girl is a good thing. (Available on Amazon.)