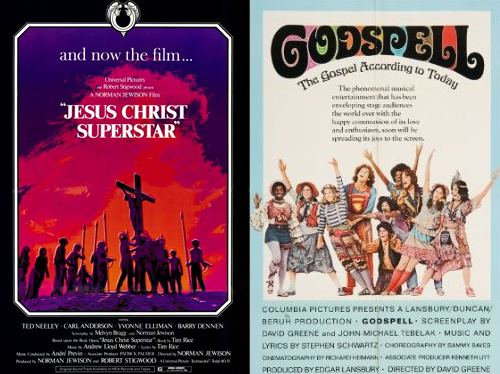

Our celebration of 1973 continues with Andrew on Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar

In 1970 John-Michael Tebelak was completing work on his master’s thesis project about Jesus Christ at Carnegie Mellon University. Before long he would pair up with musician and lyricist Stephen Schwartz and in May of 1971 the musical Godspell would officially begin playing. Around the same time, Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice were finalising work on a rock album, a concept musical of sorts, on the last ten days of Jesus' life. The album would be released in the fall of 1970, and one year later Jesus Christ Superstar, the musical developed from the soundtrack, would open on Broadway. By some weird happenstance the fates of the two Jesus musicals would be tied*. Two years later, the two musicals (both moderate hits on stage by that time) saw screen adaptations released in 1973.

In 1970 John-Michael Tebelak was completing work on his master’s thesis project about Jesus Christ at Carnegie Mellon University. Before long he would pair up with musician and lyricist Stephen Schwartz and in May of 1971 the musical Godspell would officially begin playing. Around the same time, Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice were finalising work on a rock album, a concept musical of sorts, on the last ten days of Jesus' life. The album would be released in the fall of 1970, and one year later Jesus Christ Superstar, the musical developed from the soundtrack, would open on Broadway. By some weird happenstance the fates of the two Jesus musicals would be tied*. Two years later, the two musicals (both moderate hits on stage by that time) saw screen adaptations released in 1973.

One religious stage-musical adapted to the big screen is a curiosity; two religious film musicals – both of them from recent stage hits - in a single year is fascinating. Two religious film musicals in the same year from recent stage hits which both cover, generally, the same subject? Too intriguing to ignore.

Two Jesus musicals, two very different Jesuses. More...

Both shows, trace the adult life of Jesus Christ and his relationship with his apostles. Both musicals end with a crucifixion, sans resurrection. But, their journeys to that common end are vastly different. The music of each indicate this immediately. The agitated rock overture of Jesus Christ Superstar which the film opens with, promises sharp urgency which the entire Oscar-nominated score of seventies inspired rock timbres and synthesised sounds delivers. Contrast that with the soft, harmonised melodies of Godspell, which veer closer to seventies folk music. From the opening scene the divergence is clear: rock overtures playing over images of sandy deserts to the sound of the flute playing over a busy New York street. And that's as good a place to begin as any: setting.

In adapting stage plays to film the challenge of "opening them up" always arises. The 1973 religious duo’s approach to the idea of opening up their musicals for the screen intrigues in the way setting informs their themes. Godspell is all about convincing people of the accessibility and nearness of god, what better way to show that accessibility than by having he and his disciples trek through the most popular city in the world? Nothing suggests contemporary life as immediately as the streets of New York City. Jesus Christ Superstar, a mounting of the last days of Jesus as a passion (musical) play, playing out on the mountainous coast of Jordan gives it an immediate sense of meaningfulness but also naturalism. The significance of the desert goes deeper, though. In the Bible the desert is often used as a symbol of solitariness, a place not watered by the word of God. How nifty, then, is the the image of a lone bus arriving on an expanse of abandoned desert in Jesus Christ Superstar.

Writer/director Norman Jewison frames the entire film on the conceit of a group of actors travelling to the desert to re-enact the passion of the Christ. What better way to water the isolated desert than with a bus carrying the story of Christ? It explains why the Jerusalem of Jesus Christ Superstar feels like a weird mix of the contemporary and the archaic; the Jerusalemn scenes are part a fabricated world within the "reality" of the film. The overture sees the actors assembling their props and putting on costumes the music raises to a crescendo just as we final spy our “Jesus” as he’s surrounded by the others and risen aloft. Jesus, quite literally, emerges from the band of actors. It sounds innocuous but on film it feels momentous, and it’s that sort of momentousness which drives the entirety of Jesus Christ Superstar. Say what you will about Rice’s deliberately anachronistic libretto but Jewison and cinematographer Douglas Slocombe are giving this story to us through immaculate lens and it feels important. Unsubtle, yes, but as Rice’s lyric says

…don't rely on subtlety. Frighten them, or they won't see.

Jesus Christ Superstar emanates from one of the oldest traditions of drama – the passion play. There’s little that is subtle about the genre, the directness of Jesus Christ Superstar is not indicative of its lack of finesse but part of its point. Especially when, the film is using the passion-play device not just for the religious tale of Christ's last days on earth but more general themes like the relationship between the political celebrity and the interpersonal demands of the human.

Godspell, in contrast, is not about individuality or the personal. Names are unimportant, it’s all about the church as a community. In fact, at times it's focused on the religious to its own detriment. Technically Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar are telling analogous story, or at least heading in the same direction. But, whereas the latter is showing us the progression of a story about bibilical characters through music and lyrics, Godspell is trying to dramatise the biblical experience. It’s why Tebelek wrote his libretto in the first place, to make religious services contemporary and accessible. So, Godspell the play and the film, is not really a story. Instead it is a series of parables from the Gospel of St Matthew (and a few from Luke). There is no overarching plot, it should feel unformed and spontaneous – Jesus and nine followers who grow to love him, discuss morals and religious intent through song and music. They are overcome with religious fervour. And then he dies. That’s the “story”. Or lack thereof, because it’s not about the story about the religious experience and it’s on that note I wonder if Godspell has its cards stacked against it.

Storyless narratives can work on film, but evoking religious fervour works best in person with corporeal beings in front of us. In the original production of Godspell the cast joins the audience for wine and bread after they sing “Light of the World” allowing the cast of apostles and Jesus to be one with the common man. In the film, which but for its opening and closing, only features the main cast no such effect is given. No such effect is possible. And that becomes the crux of the reason that Godspell seems just not quite right on screen. As a musical Godspell’s entire thrust is about showing that Jesus is reachable and touchable. That is why it pops onstage. That sense of nearness is one thing that makes live theatre so special, it’s why people go to church for fellowship instead of watching TV sermons. The film tries to get around the divide between cast and audience canny ways, like Jesus in the Superman T-shirt (what's more modern and relatable than a Superhero?). Or in its multiple pop culture references, for example when the performer singing “Turn back O Man” seems to be aping Barbra Streisand, or another later number playing like the film's own version of “Officer Krupke”. It's amusing, but ends up feeing more forced than natural. Having the group of ten run around New York City alone ends up making them seem even more inaccessible. David Green had his film debut with Godspell and he’d go on to direct the TV epic Roots. Godspell is, in fairness, very pleasant and I suspect the lack of noticeable visual panache is to not distract from the simplicity of the message but it ends up working against the film which feels too easy, too pleasant, too easy to look away from. By the time Jesus meets the Phirasees (played by an odd electronic contraption) and gets crucified, it's as if we never really met him and so we don't care enough.

And, the crucifixion and lack of a resurrection... It’s something the original stage versions of both plays were criticised for by the religious – the suggestion that Jesus does not rise unsettles. Its effect in Jesus Christ Superstar is particularly chilling. The passion play over, the cast shed their costumes and head back to the bus except for Ted Neely/Jesus who remains on the cross and they all drive off. I remember as a child being so unsettled by this, and it gives the entire film such an ambiguous ending. Is Jewison trying to tell us that, ultimately, everyone just abandons Jesus and his ideals on the cross as they drive off? The final shot of the shows an empty cross flanked by a setting sun and a shepherd on his flock. It’s rich in imagery, but one of the more subtle moments of the film for its ambiguity. Similarly there is no resurrection of Jesus in Godspell but his apostles carry his body through the street singing. It’s not at all macabre, it’s a literal manifestation of the apostles taking Christ to the streets and it works for Godspell – underscored by the tragedy of Jesus’ death but bizarrely managing to seem hopeful nonetheless. If the entire film is not as wholly successful at least Godspell nails its landing. And it returns me to the music. The ambiguous ending of Webber and Rice’s musical is as taut and unresolved as their music which entertains but also (deliberately) distresses. In Godspell, though, Schwartz is all about the good vibes, the music is invariably pleasant and even at its vaguest and most unformed (I can never say that I particularly like Godspell) it is an emphatically pleasant experience.

And, the crucifixion and lack of a resurrection... It’s something the original stage versions of both plays were criticised for by the religious – the suggestion that Jesus does not rise unsettles. Its effect in Jesus Christ Superstar is particularly chilling. The passion play over, the cast shed their costumes and head back to the bus except for Ted Neely/Jesus who remains on the cross and they all drive off. I remember as a child being so unsettled by this, and it gives the entire film such an ambiguous ending. Is Jewison trying to tell us that, ultimately, everyone just abandons Jesus and his ideals on the cross as they drive off? The final shot of the shows an empty cross flanked by a setting sun and a shepherd on his flock. It’s rich in imagery, but one of the more subtle moments of the film for its ambiguity. Similarly there is no resurrection of Jesus in Godspell but his apostles carry his body through the street singing. It’s not at all macabre, it’s a literal manifestation of the apostles taking Christ to the streets and it works for Godspell – underscored by the tragedy of Jesus’ death but bizarrely managing to seem hopeful nonetheless. If the entire film is not as wholly successful at least Godspell nails its landing. And it returns me to the music. The ambiguous ending of Webber and Rice’s musical is as taut and unresolved as their music which entertains but also (deliberately) distresses. In Godspell, though, Schwartz is all about the good vibes, the music is invariably pleasant and even at its vaguest and most unformed (I can never say that I particularly like Godspell) it is an emphatically pleasant experience.

And, yet, even though Jesus Christ Superstar is the only one I'd say completely succeeds I’m happy that both of these films exist. What a time to be alive in 1973 when TWO stage musicals could be adapted to the big screen just two years after their premieres. Look at the last 20 years of major stage to screen musical adaptations, the closest we've come to a two-year wait for a film version was Hairspray (five years after its stage incarnation) and The Producers (four years after) and both were Tony winning musicals. But neither Godspell nor Jesus Christ Superstar was a Tony winner (the former was not even eligible). Was it a mini-religious revival in the early seventies? Were the producers of both musicals just industrious? Whatever the reason, it was all for the best.

*The fates of Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar continue to be – bizarrely – intertwined. In the 2011/2012 Broadway season Godspell began performances of a revival in October 2011 and the revival of Jesus Christ Superstar began official performances a few months later in March.