Episode 33 of 52: In which Katharine Hepburn is like the Goddess from the Machine.

I want to write about Katharine Hepburn, but the movie keeps getting in the way! Reading last night’s contributions to Hit Me With Your Best Shot, I was struck by how many bloggers described Suddenly, Last Summer as “camp,” “wildly expressive,” or “absolutely batshit gonzo crazy.” This is a film that will not be ignored. It’s garish and shocking. The psycho-babble hasn’t aged well--as Nathaniel points out, such things rarely do. The themes of cannibalism, sexual deviance, and monstrous madness creep like kudzu vines hanging in Violet Venable’s garden, blocking the light and threatening to squeeze the resistance out of unwary viewers who venture into the film unwarned.

I want to write about Katharine Hepburn, but the movie keeps getting in the way! Reading last night’s contributions to Hit Me With Your Best Shot, I was struck by how many bloggers described Suddenly, Last Summer as “camp,” “wildly expressive,” or “absolutely batshit gonzo crazy.” This is a film that will not be ignored. It’s garish and shocking. The psycho-babble hasn’t aged well--as Nathaniel points out, such things rarely do. The themes of cannibalism, sexual deviance, and monstrous madness creep like kudzu vines hanging in Violet Venable’s garden, blocking the light and threatening to squeeze the resistance out of unwary viewers who venture into the film unwarned.

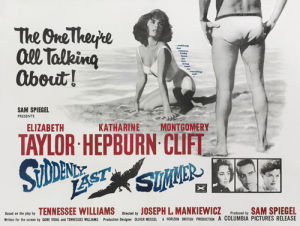

This unsettling excess had been, up to that point, unusual for director Joseph L. Mankiewicz--best known for character dramas--but can be easily traced to his collaborators. Gore Vidal adapted Tennessee Williams’s short lyric play about a rich widow’s attempts to hide her dead sons secrets by lobotomizing her niece into a Southern Gothic by way of Freaks. There are scenes with sanitariums and gardens, and many things are said. In fact, you might overlook how talkative the film is thanks to Jack Hilyard’s beautiful black and white cinematography. Elizabeth Taylor and Katharine Hepburn (both Oscar nominated) battle over and between Montgomery Clift against the lurid Louisiana locations created by Oliver Messel and William Kellner (also nominated). In short, this film is sensory overload.

But I digress. This series is about Katharine Hepburn, not censorship or deviance or strong production design. One shot stands out to me as the definitive Best Shot when discussing Kate’s turn as Violet Venable: an empty chasm in the ceiling into which Dr. Cukrowicz gazes as the elevator whirs to life. You hear Violet Venable before you see her...

Best Shot

Best Shot

In a moment, Violet will descend in an open elevator, making arguably one of the best entrances in Hollywood history. But it’s not about what you see. It’s about what you hear. Violet's voice, commanding and charismatic, floats down even before she appears in her angelic white dress. This isn't the first time Kate's voice has preceded her in a film--a similar trick was used in Woman of the Year. However, the lilting playful growl Kate employs is totally new. It’s an entrance that demands that attention be paid. Watch (or rather listen) to Violet's entrance.

Though he hated the movie, Tennessee Williams had this to say about Kate's performance:

“Kate is a playwright’s dream actress. She makes dialogue sound better than it is by a matchless beauty and clarity of diction, and by a fineness of intelligence and sensibility that illuminates every shade of meaning in every line she speaks.”

That’s a far cry from the critics of the past, who had declared Kate’s voice “breathless” and “offkey.” Katharine Hepburn’s peculiar Mid Atlantic dialect has always been an easy target for impressionists, but don’t ignore the evolution and technical skill she gained as she matured. By 1959, Kate been working a decade in Shakespeare, learning to appreciate language and slow down the infamous rapid fire, Bryn Mawr patter. Her guides for the first half of the 1950s were Constance Collier, a character actress who’d played Kate’s acting teacher onscreen in Stage Door, and a vocal coach named Alfred Dixon, who taught her diaphragm control. For the rest of the 1950, Kate honed her craft onstage, but she didn’t get an opportunity until 1959 to translate these skills to the screen.

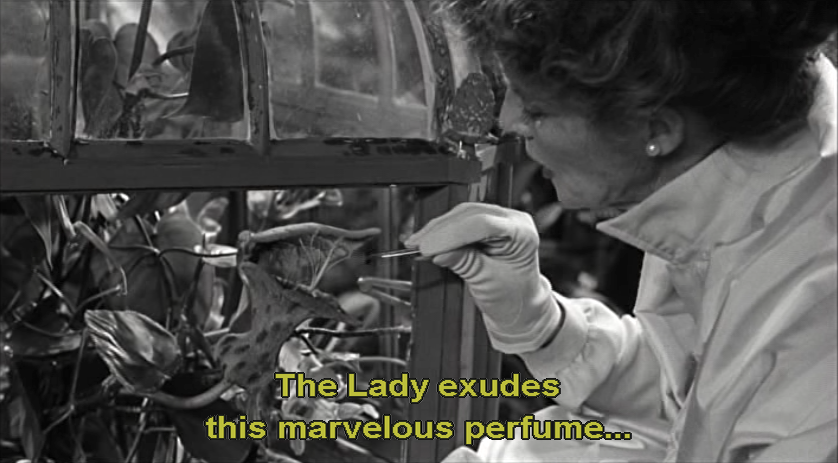

As Violet Venable, Kate practically sings her lines. Gore Vidal added to Tennessee Williams’s original dialogue with monumental monologues of his own (including the Violet’s entrance), and Kate shows her appreciation for the two wordsmiths by delivering their lines with care. Depending on the situation, Kate can whip herself into a shaky frenzy over flesh-eating birds, retreat into clipped consonants when entertaining relatives, or stretch a speech about carnivorous plants and savor each syllable like molasses. At the height of her powers, Kate trails off into the predatory purr of a leopard in her lair. It is a full-voiced performance.

Unfortunately, it’s not a full-bodied performance. Kate never fully commits to Violet. Instead, she allows Violet to slip blankly into her moments of madness without inhabiting the human beneath. This fits well with the film, which demonizes mental illness. But though Kate shows true technical prowess, her theatricality comes at the expense of complexity. Ultimately, Violet is a supporting player not on par with Elizabeth Taylor's Cathy. Instead, Violet Venable is left soulless: a madwoman, a mother, and a monster.

Nevertheless, Suddenly, Last Summer represents another milestone for Kate the Great. Hepburn had spent the 1950s establishing herself as both Great Actress through her spinster roles and Great Star through her comedies. She was loveable and laudable, which is why Suddenly, Last Summer is such a shock. Not once in a quarter of a century onscreen had Katharine Hepburn ever played a villain, much less one with second billing. The risk--though not the second billing--was a sign of things to come. Suddenly, Last Summer is more comfortably grouped with her work in the 1960s, an acting streak that resulted in 4 nominations (and 2 wins) in a row. More importantly, the films of the 1960s are as much defined by their riskiness as their Oscar chances. In 1960, Kate turned 53, and the greatest era of her career was about to begin.

Previous Week: Desk Set (1957) - In which Katharine Hepburn plays a woman named Bunny who starts a battle of wits with Spencer Tracy's computer. That's actually the plot.

Previous Week: Desk Set (1957) - In which Katharine Hepburn plays a woman named Bunny who starts a battle of wits with Spencer Tracy's computer. That's actually the plot.

Next Week: Long Day's Journey Into Night (1960) - In which Katharine Hepburn enters the golden age of her career.

Make sure to check out the other entries in Hit Me With Your Best Shot to unpack more of what this dense, deliciously weird movie has to offer!