Episode 38 of 52: In which even Katharine Hepburn and Vanessa Redgrave cannot save a 3,000 year old stinker.

As a budding theater and film student, my freshman year of college I landed in Intro to Set Design. The professor, a thespian in the grand academic style garbed oversized scarves and an air of intellectual enlightenment, explained to us that our final project would be a rules-free design for The Trojan Women by Euripides. “After all,” she said with a weary sigh, “you can’t make it any worse.”

As a budding theater and film student, my freshman year of college I landed in Intro to Set Design. The professor, a thespian in the grand academic style garbed oversized scarves and an air of intellectual enlightenment, explained to us that our final project would be a rules-free design for The Trojan Women by Euripides. “After all,” she said with a weary sigh, “you can’t make it any worse.”

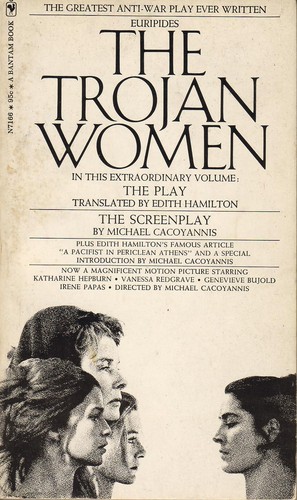

Low praise for high art, but her reasoning was sound. Though The Trojan Women is subversive and surprisingly modern in theme, the play seriously lacks structure. (The year Euripides offered The Trojan Women at the Dionysia theater festival, he placed second out of two.) Beginning immediately after the downfall of Troy, The Trojan Women laments the enslavement, rape, and murder of the women of the captured city. Unfortunately, Euripides fails to tie his diatribe to a plot until late in the play, resulting in a funereal dirge. Like Euripides’s tragedy, Michael Cacoyannis’s 1971 film adaptation is full to brimming with good ideas that ultimately fail to coalesce into something great.

One of these actresses steals the movie after the jump...

Good Idea #1: An All Star Female Cast. Our own Kate plays Hecuba, Queen of Troy. Vanessa Redgrave plays Andromache, widow of Trojan hero Hector. Genevieve Bujold plays the mad prophet Cassandra. Irene Papas--the only ethnically Greek actress--plays Helen of Troy. Unfortunately, Cacoyannis burdens these incredible actresses with acting in the declamatory style, well-suited and more or less historically correct for Greek tragedy, but terrible for film. As a result, though the stars act (loudly), they rarely interact or react to each other. Kate, who has had difficulties responding to her fellow actors before, is the most egregious offender.

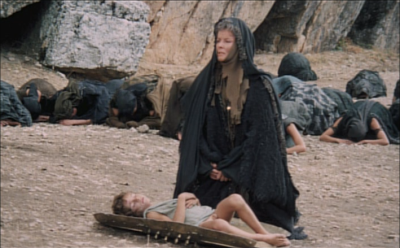

Good Idea #2: Hiding Helen of Troy. I’d say Irene Papas walks away with The Trojan Women, but it’s more accurate to say that Cacoyannis hands her the film. From her introduction, stripping bare to wash herself in a basin of water while the angry Trojans throw stones, Helen is both forbidden and forbidding. Papas breathes life into the film during the trial, when Helen is forced to beg, threaten, and ultimately seduce her husband Menelaus into allowing her to live. Papas lights a fire under Kate as well. Pitted against Helen, Hecuba loses her shallow histrionics, delivering her impassioned invective to Menelaus with anger, grief, regality, and regret. Unfortunately, after Helen exits (aboard her husband’s ship and very much alive), Hecuba (and Kate) falls back into droning doldrums.

Good Idea #3: Grounding Stylized Tragedy in Reality. Cacoyannis builds the crumbling walls of Troy on the white, dry dust of Spain, photographed in harsh natural light and a documentary style. He also cuts the gods from the prologue and turns the Greek Chorus into a seething mob of mourning women. These leanings towards realism would work but for the equally extreme decisions in the opposite direction. The Greek Chorus still breaks the fourth wall, usually in startling tableaux that are beautiful-but-stagey. (Also, too much zoom, cameraman. Way too much zoom.) The result is tonally fractured and confused.

The Trojan Women was another example of Kate’s impressive insistence on aligning herself with great playwrights. Unfortunately, this was a risk that didn’t pan out. It seems to have scared her away from classics permanently, since she never did an adaptation of a play more than 30 years old again. (Pity, too. I’d have loved to see her team up with Zeffirelli to do some Shakespeare.) Maybe Kate herself was worried about becoming a relic. In a Life Magazine cover story 3 years earlier, she’d stated,

“There comes a time in your life when people get very sweet for you… I think they’re beginning to think I won’t be around much longer… And what do you know: they’ll miss me like an old monument--like the Flatiron Building.”

Perhaps Katharine Hepburn was beginning to wonder about her legacy. Whatever the case, the camera-shy, publicity-loathing actress was about to do something she never did. She was about to sit down for an interview.

Previous Week: The Madwoman of Chaillot (1969) - In which Katharine Hepburn plays another aristocrat in an odd little movie that makes no sense.

Previous Week: The Madwoman of Chaillot (1969) - In which Katharine Hepburn plays another aristocrat in an odd little movie that makes no sense.

Next Week: A Delicate Balance (1973) - In which Katharine Hepburn stars in an Edward Albee play that's not Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and does her first television interview.