It's Tim. September marks the centennial of famed director Robert Wise, winner of Oscars for the musicals West Side Story and The Sound of Music among several other classic films, and the members of Team Experience are going to spend the next several days revisiting work from the entire range of his career. And what better place to start than at the very beginning: 1944's The Curse of the Cat People, which was Wise's directorial debut, taking over from Gunther V. Fritsch, when the project fell behind schedule. It's part of the legendary run of movies produced by Val Lewton's horror-oriented B-unit at RKO, a studio where Wise had already logged time as an editor (cutting both Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons, no less). But it's not, itself, a horror movie, despite being the sequel to Cat People, one of the canonically great horror films in history. And despite Wise having a terrific hand for horror, as he'd first prove with his third feature, the Lewton-produced The Body Snatcher.

It's Tim. September marks the centennial of famed director Robert Wise, winner of Oscars for the musicals West Side Story and The Sound of Music among several other classic films, and the members of Team Experience are going to spend the next several days revisiting work from the entire range of his career. And what better place to start than at the very beginning: 1944's The Curse of the Cat People, which was Wise's directorial debut, taking over from Gunther V. Fritsch, when the project fell behind schedule. It's part of the legendary run of movies produced by Val Lewton's horror-oriented B-unit at RKO, a studio where Wise had already logged time as an editor (cutting both Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons, no less). But it's not, itself, a horror movie, despite being the sequel to Cat People, one of the canonically great horror films in history. And despite Wise having a terrific hand for horror, as he'd first prove with his third feature, the Lewton-produced The Body Snatcher.

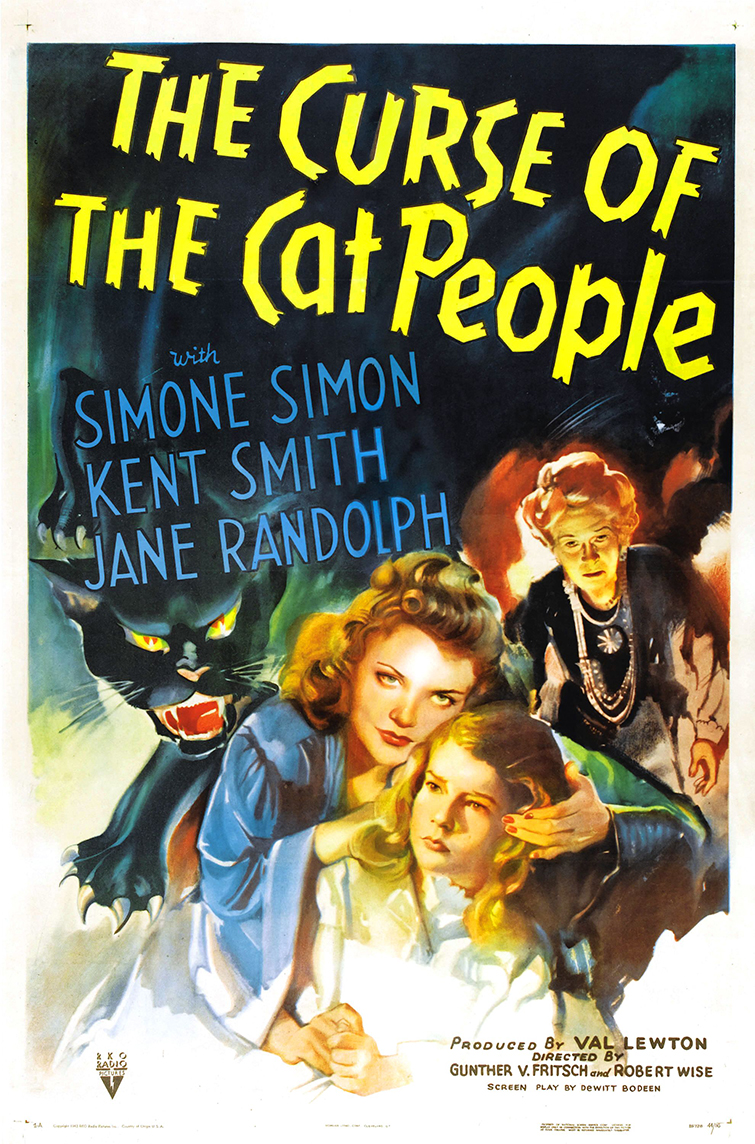

The Curse of the Cat People is, rather, a sort of psychologically realist fairy tale, taking its title (which RKO forced upon Lewton, though giving him the freedom to make any plot he wanted to under that name) to the most symbolic, abstract extreme possible. It involves Oliver Reed (Kent Smith) and his wife Alice (Jane Randolph), the heroes of the earlier film, moved to the New York suburbs with their six-year-old daughter Amy (Ann Carter), who's having a problem separating fantasy from reality lately. And the audience is forced into having much the same problem, when Amy wishes for a friend and gets one in the form of Irena (Simone Simon), whom devotees of Cat People might recall was Oliver's first wife. The one who transformed into a panther when she got sexually aroused, and is dead now.

The thing that DeWitt Bodeen's screenplay is about is certainly not whether Irena is a ghost or a figment of Amy's imagination, and it's even less about whether Irena's cat problem from the first movie is going to come back in the present. It is about child psychology: the way that a little girl might use fantasy and imagination to cope with the world around her, one that isn't always friendly or accommodating. And how that fantasy might actually be quite a useful thing to create a safe space for learning and maturity, and how bullying, rationalist dads who ought to know better (having seen their late wives transform into damn panthers already) can sometimes be more harmful in trying to help their children grow-up, than by allowing them to be children.

Not a conventional theme, by any stretch of the imagination, especially for any of the people who put it together: nothing about this first Robert Wise film necessarily screams "Robert Wise made this", though the topic of people fumbling around in trying to understand the needs of others would pop up in some form in everything from West Side Story to Star Trek: The Motion Picture.

Which isn't to say that the directing isn't distinctive and fairly terrific. With Nicholas Musuraca, a reliable creator of noir-ish shadows and gloom, Wise's approach here was far more delicate than anything else in the Lewton canon, with an obvious and mostly successful attempt to frame everything from Amy's perspective, both in terms of camera angles and the subjective experience. Buildings are wondrously tall, snowy backyards are enchanted playgrounds, the hallway outside the teacher's office is a hellish pit of despair.

Most importantly, Wise got a tremendous performance out of Carter, preserving a guileless, unknowing innocence that nevertheless feels directed and purposeful, and not just the result of having a kid much about in front of the camera. It is as close to flawless as child performances get, and having the whole movie structured around it only calls attention to how complex and subtle the film and filmmakers allow Carter's performance to be. Wise didn't do much in the way of directing children in later years; a pity, for this suggests he'd be great at it. And yet, building the visuals around the character of Amy and Carter's performance does point to one of the things he'd be best at in later years: building spaces as an extension of character psychology, no matter how realistic or impressionistic those spaces might have been. The Curse of the Cat People is as odd a first film as a director could possibly have, but it gave Wise a chance to flex his muscles with exteriorizing emotions and playing outside of the normal rulebook of genres, two things that would define his movies to come for the rest of his career.