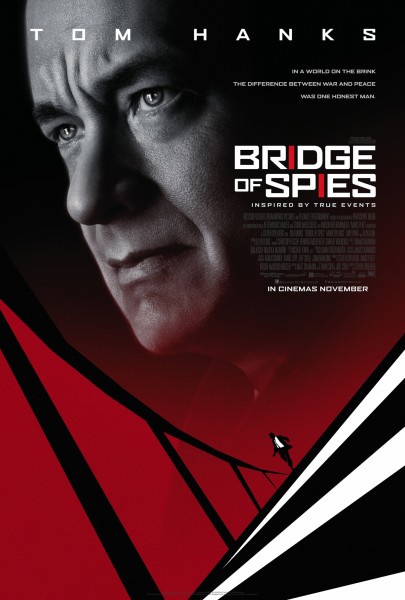

Manuel reporting from the New York Film Festival on Steven Spielberg's latest Cold War film.

Bridge of Spies opens with a man working on a self-portrait. There’s a weariness to his features that he’s ably translating from his mirrored reflection onto his canvas. There’s a purpose to every brush stroke he takes. He works methodically. Silently.

Bridge of Spies opens with a man working on a self-portrait. There’s a weariness to his features that he’s ably translating from his mirrored reflection onto his canvas. There’s a purpose to every brush stroke he takes. He works methodically. Silently.

Spielberg, long admired for large-scale adventures and expertly crafted action sequences, seems to have entered a quieter phase of his career. While War Horse seemed to play to his strengths, while trying John Ford on for size, the talky Lincoln showed that the director could create a kinetic urgency even in what was, for the most part, a chamber piece about laws and votes. Bridge of Spies pushes further still in this direction. Yes, we’re dealing with spies, and fallen aircrafts, government agents and tense phone calls, but at its heart, this is yet another installment of the Cold War-as-bureaucracy genre. [More...]

Tom Hanks plays James B. Donovan, a cunning life insurance lawyer who cut his teeth during the Nuremberg trials who is tasked by his firm to represent Rudolf Abel (a beautifully understated Mark Rylance) in a court of law after he’s charged with being a Soviet spy. Hanks is, as usual, playing off his All American charm to great effect: Donovan is perhaps the only lawyer that would take the case in earnest, going all the way to the Supreme Court to defend his client’s rights even while everyone else understands the trial as mere pageantry. His stern and unwavering belief in the Constitution guide him even as he puts his family in danger (yes, Amy Ryan, has little to do other than play the requisite “supportive wife” role; Billy Magnussen at least gets the most out of his brief scenes as a doe-eyed lawyer helping Donovan with the case).

All of that, as it turns out, is mere setup, with the bulk of the film taking place in Berlin at the time the wall was being erected, where Donovan is to negotiate the exchange of Abel for a recent American spy pilot (Austin Stowell) caught by the Soviets. There is, of course, as a character puts it, a “wrinkle” in the simple exchange which complicates things. What follows is plenty of intrigue, a lot of smoke and mirrors, and most of all, a lot of talking before the exchange at the eponymous bridge takes place. For a Spielberg film, it’s surprisingly barren of flashy set-pieces that focus on action. Instead, the film plays almost like a languid Jon LeCarré novel, if one filtered by the star-spangled sentimentality that not even this most restrained of Spielbergs can resist.

By the end of the film that very first image of Abel painstakingly working on his self-portrait came to mind. It functions as a metaphor for the entire film: Bridge of Spies is the type of movie one describes as “handsomely made.” On a below-the-scenes technical level it is a marvel: the snow-covered streets of East Berlin look as chilly as the Cold War politics they come to represent; the various grey-hued coats and suits that crowd the screen call out and deny individuality, while sunlight becomes oppressive and intrusive in this claustrophobic film which takes place in prison cells, boardrooms, and seedy hotels. Even seemingly clichéd spy genre images (a lone man in an umbrella in the moonlit rain, a conversation with an agent at a smoky dive bar) are presented with renewed vigor.

If my sentences suggest admiration rather than outright passion, it is because, other than during its dazzling near-wordless opening sequence, I was never taken by it as a whole. Much of it has to do with the film’s screenplay (written by Matt Charman with credited rewrites by the Coen brothers) which is great at long, sustained setups, but less effective by the time the film reaches its all too-tidy resolution.