Jose here. When I scheduled my interview with director Germán Tejeira who is based in Montevideo, I hadn’t been counting on the internet being unaware that Uruguay had gotten rid of their own Daylight Savings Time, a practice which was deemed “old fashioned” and “inefficient” by the progressive government. We had to reschedule the interview, but Tejeira was kind enough to laugh the confusion off and even sent me an article which explained how this new practice had brought chaos within his own country. It was an anecdote I found peculiarly surreal, something out of a movie perhaps, and one that for that matter reminded me of Tejeira’s own A Moonless Night, a charming account of three men trying to find their, existential, way in the Uruguayan countryside during New Year’s Eve.

Jose here. When I scheduled my interview with director Germán Tejeira who is based in Montevideo, I hadn’t been counting on the internet being unaware that Uruguay had gotten rid of their own Daylight Savings Time, a practice which was deemed “old fashioned” and “inefficient” by the progressive government. We had to reschedule the interview, but Tejeira was kind enough to laugh the confusion off and even sent me an article which explained how this new practice had brought chaos within his own country. It was an anecdote I found peculiarly surreal, something out of a movie perhaps, and one that for that matter reminded me of Tejeira’s own A Moonless Night, a charming account of three men trying to find their, existential, way in the Uruguayan countryside during New Year’s Eve.

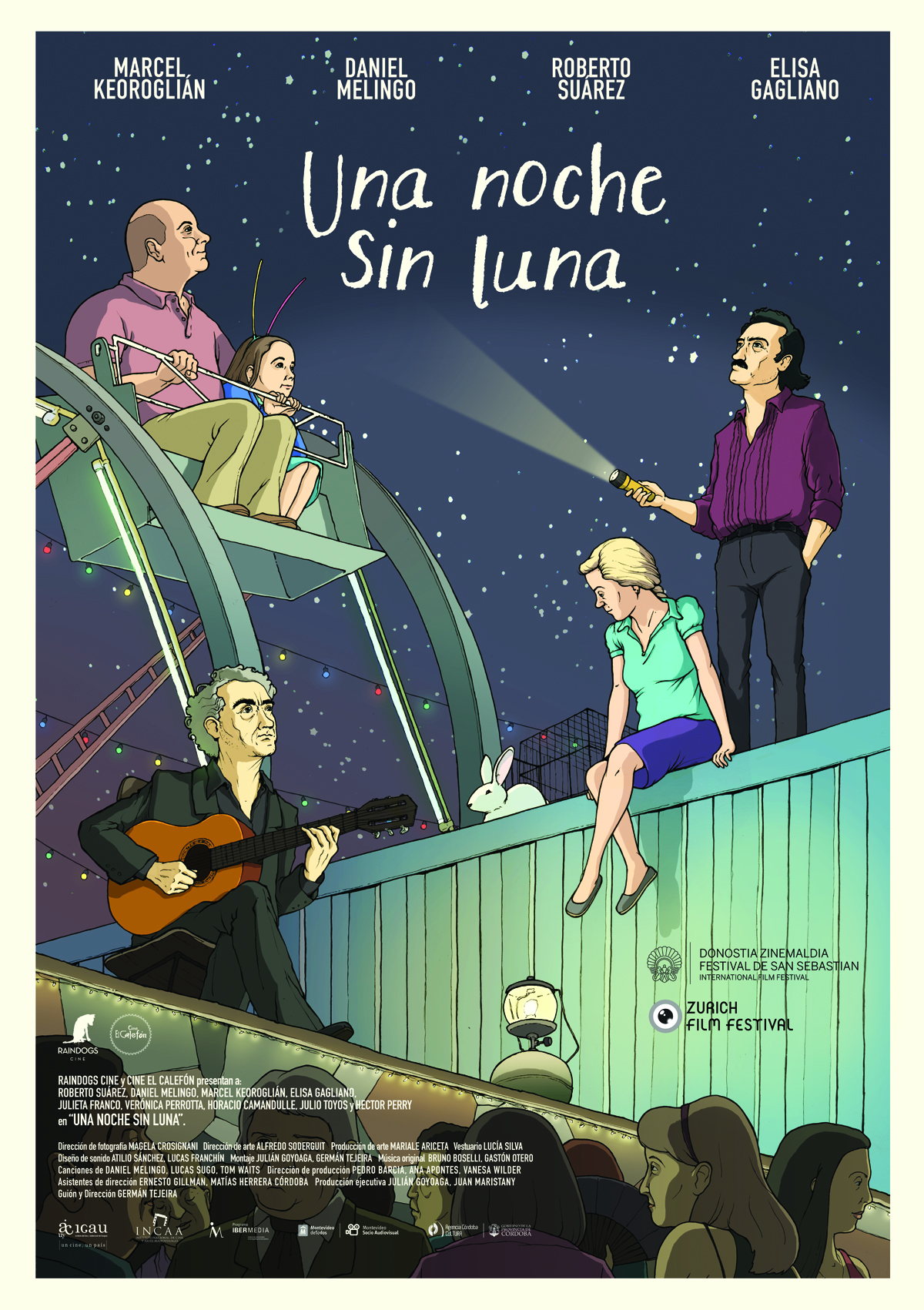

Cesar (Marcel Keroglian) is a cab driver spending the holiday with his ex-wife’s new family, Antonio (Roberto Suarez) is a magician en route to a presentation whose car breaks down stranding him and his rabbit Oliver, Molgota (Daniel Melingo) is a singer released from jail a day earlier so he can perform at a New Year’s party. Their routine is altered by a blackout, but to say their stories cross paths in a traditional way would be a disservice to Tejeira’s lovely screenplay, and his perceptive direction. The film has been selected as Uruguay’s Oscar representative and I discussed that with the director, as well as his perception of what films should provoke in spectators, and whether Uruguay has a well defined “cinematic identity”.

Read the interview after the jump...

JOSE: Thanks for being so flexible with the scheduling, it’s strange how the rest of the world doesn’t seem to know Uruguayan time has changed.

GERMAN TEJEIRA: I thought the internet would’ve been updated by now. The day the time changed officially, I slept in until noon and woke up surprised it was already so late. It was a mess, people showed up to work earlier.

JOSE: I feel like there’s a movie in there somewhere.

GERMAN TEJEIRA: (Laughs)

JOSE: It made me think a lot about A Moonless Night and how an incident you can’t control, like the blackout in your film, can set in motion a lot of unexpected changes in people’s lives. I grew up in Latin America, so I remember blackouts pretty well, and your film reminded me of the things I imagined were going on when the lights were gone. How did you come up with the idea to use a blackout as the element that sets the film in motion?

GERMAN: I went to a Daniel Melingo concert in 2004, he also sings in the film, he’s a very known musician in Uruguay and I remember at this show there was a blackout. But he kept singing with his band for another 40 minutes or so, which made for a truly beautiful, intimate moment. I told Melingo about this later and he told me once people realized how magical blackouts were, they’d started doing faux blackouts at other shows.

When I was a kid there were “programmed blackouts”, in which the government would warn you there would be no power in your neighborhood for a specific period of time. So people had no choice but to get together and talk, play cards, it also made for moments of intimacy. Blackouts change your perspective so much, there’s a famous Uruguayan author who says they can be the greatest spark for creativity.

Curiously two of the main characters in your film are artists, and we see how lonely their lives are because they’ve dedicated all of it to their craft. Do you personally feel artists lead lonelier lives?

I’m not sure about that. It’s an interesting point of view, but it never crossed my mind. I wasn’t trying to have the last word on the topic or anything, what I do know is that when are artists working at parties, they are the only people - along with the servers - who aren’t there to celebrate. Perhaps this idea of watching others celebrate is what can be lonesome.

Even though the film uses three characters as its axis, it’s not necessarily a film about these three people. How easy was it to give the film such a tight structure when it could’ve gone in a million different directions?

It was hard because I’d originally wanted to do something different. I wanted to borrow the structure of Jarmusch’s Mystery Train, which has one story, then another, then another...and a finale in which the stories lightly touched on each other. However, in the editing room we realized our stories worked better if they all reached a point, the blackout in this case, and then the next one began. Finally they all had its climax in the end. Also, in the screenplay the first story was the one we ended up placing in the middle, the magician’s tale, which I thought would be a more inviting tale to begin the movie with. However in the editing room, we realized the cab driver’s story would be easier to recognize and for people to identify with.

All of these characters are so layered that I wonder if you know their whole lives, or are they merely invoked for the film?

I know their fates. I know what happens to them after the film, and I know some things about their lives before. All of the characters are at a point in their lives when they want to change something about themselves. For instance I know why the musician is in jail, why the cab driver’s wife left him. I also used these secrets to work with the actors, for instance if the musician is in prison for murder, it’s different than if he’d committed fraud, and our perception of the character would have been very different.

As a filmgoer do you tend to prefer films that reveal less rather than more?

I broke my leg which limits my mobility a lot, so just yesterday I was in bed working on a crossword and it pointed out that the words image and enigma in Spanish have the same letters (imagen/enigma). I’ve been thinking about it a lot, because it’s true, the images that are often most powerful are those we find enigmatic. Ronald Melzer, a Uruguayan film critic who passed away recently, saw an animated film we made called Anina, and wrote a beautiful review about how the film had reminded him of his childhood so much, especially because of how we used bicycles. I told Ronald there was not a single bicycle in the film, so he told me films were about what we brought to them. I think he was right, the more you put of yourself in the film, the more the film plays with you and reveals its layers.

Right, a great film like a mirror, should be able to reflect you. This is your first feature length, and everything is so well defined that I found it incredible you’d only done shorts before. Was it hard to find your voice?

I was nervous all the time (laughs), I think the beauty of filmmaking is in its collective nature. I’ve been working with the same team for years, so the trust we had in each other was immense. I’d started working on this screenplay in 2004 and we finished the film in 2014, so obviously there was a lot of team effort involved. Also as a director, you kinda need to know where you’re headed, and then listen to what other people say. If filmmaking was like music, you could say the art director, costume designer etc. all need to have their instruments tuned, and all you need to tell them is what piece we’ll be playing. Directing is easier than what people think.

As an Uruguayan filmmaker, would you say there is a clearly defined “Uruguayan cinema”? Your film reminded me of intimate dramas like Whisky and Leo’s Room, which have plots where nothing happens and yet everything does.

I’m about to say something and then contradict myself, so bear with me. Yes, there is such a thing as “Uruguayan cinema”, which is the kind of filmmaking started by Juan Pablo Rebella and Pablo Stoll in 25 Watts and Whisky, which helped put Uruguay in the festival circuit and feels very Finnish so to speak. These sad comedies with existential undertones...I’m always bothered by this idea of “small stories”, because if you do a film about robots planning to destroy the planet it’s epic, but a story about a father trying to win back his daughter’s love is a “small story”, I personally think the father’s story is much more epic. We know humans always beat the robots anyway. So yes, these intimate stories are “Uruguayan cinema”.

On the other side, even though Uruguayan film production is small, within what gets made there are so many genres! None of the local films have anything to do with the other, we make horror films, animated films, soccer documentaries...if I owned a videoclub for instance, I wouldn’t have a “Uruguayan Film” section, I’d take each of the films and put them in their genre. No one owns videoclubs anymore though (laughs).

A Moonless Night is being touted as an art/festival film, but obviously you want to reach beyond this niche. Who would you say is the film’s target audience?

That’s a great question and I don’t really have an answer. I think our film is very “open”, families can go see it. In fact the film was shown for free at a botanical garden in Montevideo the other night, and over a thousand people showed up, which was very emotional. The little girl who stars in the film texted me to say we should get to work on a sequel. The thing is the actual theaters where we could show our film are booked by American films, and 3D movies about neurotic animated characters, but if you think about it films have a longer shelf life. Once they’re on TV, or available for streaming, they eventually reach their audience whether it’s in a movie theater or at home.

Right, speaking of which, can we talk about how you feel about your film being submitted as Uruguay’s Oscar selection?

It’s beautiful because the people who voted for us are our colleagues, actors, people you work with. As for the Oscar, it’s something that seems so far away. We’re in the long list, which will then become smaller, and honestly we don’t have the budget to market ourselves there. But it’s beautiful to represent your country somewhere, we’re waving our little Uruguayan flag and bringing it to the competition.

A Moonless Night does not yet have an American distributor.