Is “Suffragette” faltering under the weight of overly high expectations? With its impressive pedigree and unimpeachable subject matter, Sarah Gavron’s historical drama about the militant wing of the British suffragist movement seemed poised to be a strong Oscar contender for this fall. Now, as we move towards the holidays, its status is looking uncertain: reviews have been mixed, and it’s drawn criticism for everything from its limited narrative focus to the limited screen time of Meryl Streep, who receives top of the line billing for a role that’s essentially no more than a cameo.

Is “Suffragette” faltering under the weight of overly high expectations? With its impressive pedigree and unimpeachable subject matter, Sarah Gavron’s historical drama about the militant wing of the British suffragist movement seemed poised to be a strong Oscar contender for this fall. Now, as we move towards the holidays, its status is looking uncertain: reviews have been mixed, and it’s drawn criticism for everything from its limited narrative focus to the limited screen time of Meryl Streep, who receives top of the line billing for a role that’s essentially no more than a cameo.

If there’s a common trend to the criticism, it’s that the critics seem mostly preoccupied with what the movie doesn't do rather than what it does. “Suffragette” is less a historical chronicle of the suffragettes than a snapshot view through the eyes of one (fictional) working class woman who’s accidentally and at first reluctantly drafted into their ranks. It’s a study of what circumstances would drive such a woman to join a movement that would seem to hold no immediate benefit or attraction for someone in her position. [more...]

As such, it’s effective and hits all its emotional marks, even if it doesn’t quite transcend the sum of its parts.

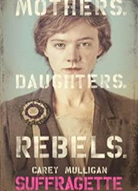

Much of what works about the film hinges on the linchpin performance of Carey Mulligan. Like a lot of Mulligan’s signature roles, it’s not a showy turn but the kind that creeps up on you, as her character, Maud Watts, gradually emerges from her quiet, compliant shell and wakes up to the dual recognition of her own strength and the profound injustice of her disenfranchisement—not just in the area of voting, but in every aspect of her life. The script, written by Abi Morgan (Iron Lady, Shame, and one of the best and most underappreciated TV series ever, “The Hour”), steers Maud towards her eventual epiphany in a way that never feels forced, even if it comes close to overplaying its hand in one wrenching scene involving her young son and a husband (Ben Whishaw, playing against type) whose cruelty is driven by weakness rather than malice.

The movie’s also remarkably balanced and unsentimental in its depiction of the dark side of the suffragette movement. It shows in sharp detail the harsh treatment the suffragettes suffered for their lawbreaking, from police beatdowns to force feedings to end their hunger strikes while in prison. At the same time, it also doesn’t shy away from casting seeds of doubt on the wisdom of the suffragettes’ more extreme, proto-IRA-style tactics—or their material impact on women like Maud, who could ill afford to be on the wrong side of law and society. Some of the film’s most interesting interactions are between Maud and the Special Branch detective, nicely underplayed by Brendan Gleeson, who’s gathering intelligence on the suffragettes and who tries to convince Maud that the movement is no friend to women of her class. Of course he doesn’t persuade her or us, yet he is persuasive as the reasonable man tasked with enforcing an unreasonable law. On the other side, Helena Bonham-Carter, Anne-Marie Duff, and Romola Garai present three different faces to the suffragette movement, more thinly sketched than Maud’s but still believable, each with different backgrounds and motivations leading to the same overarching goal.

Some viewers may find it odd that the movie ends several years before the suffragists even began to see that goal enacted in law. It’s not actually all that arbitrary a stopping point, as the final historical event shown – the 1913 Epsom Derby – did mark a watershed moment for the movement. (It’s a gripping scene, incidentally – even if you know how it ends, it’s still breathlessly tense right up to the finish.) And again, the movie isn’t trying to show the triumphal achievement of women’s suffrage; it’s showing the journey to the self-realization of Maud Watts, which takes place over the course of a particularly important year in the suffragette movement. Her arc is complete, even if that of her cause is not.

Suffragette isn’t a perfect film. It’s faulted, not unjustly, for being too white, too stodgy, too obvious in its messaging. Still, I submit it’s no more any of these things than another recently released and more widely praised historical drama, Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies. True, the latter displays superior (shall we say Spielbergian) cinematic craft and a finesse, even a touch of slyness at times, that Suffragette lacks. But I can’t help wondering if that’s the only reason Bridge of Spies has been getting better reviews. Could it be that we’re more willing to be generous to Spielberg, the Coen brothers, and Tom Hanks (who, don’t get me wrong, is terrific in Spies) for fashioning an entertaining, male-focused tale of a recognizably American, take-charge hero than we are to a lesser known British female director and writer for focusing on an oppressed woman who takes the entire film to assert full agency over her own life?

Grade: B

Oscar Potential: ???