Jose here. One could argue that most films go through an interesting trajectory, since it’s never easy to turn the initial pages on a script into moving images projected on a screen. However, few films in recent years have gone through the journey of Claudio Caligari’s Don’t Be Bad, which not only was the director’s third film in thirty years (take that Terrence Malick), but sadly turned out to be his last. Caligari, who had been diagnosed with terminal cancer, shot the film and had completed most of its editing, when he died at the age of 67 never seeing the final product. What followed was a true labor of love, as Caligari’s colleagues, led by actor Valerio Mastandrea who had starred in his second film, The Scent of the Night, completed the project and made sure it became available to audiences.

Jose here. One could argue that most films go through an interesting trajectory, since it’s never easy to turn the initial pages on a script into moving images projected on a screen. However, few films in recent years have gone through the journey of Claudio Caligari’s Don’t Be Bad, which not only was the director’s third film in thirty years (take that Terrence Malick), but sadly turned out to be his last. Caligari, who had been diagnosed with terminal cancer, shot the film and had completed most of its editing, when he died at the age of 67 never seeing the final product. What followed was a true labor of love, as Caligari’s colleagues, led by actor Valerio Mastandrea who had starred in his second film, The Scent of the Night, completed the project and made sure it became available to audiences.

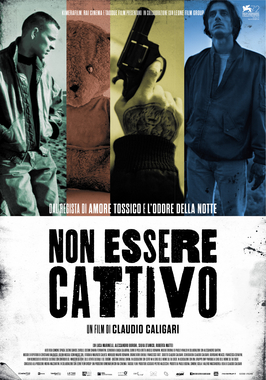

Don’t Be Bad made its debut at the 2015 Venice Film Festival and was subsequently selected as Italy’s submission for the Best Foreign Film Oscar. With a plot that seems inspired by Pasolini and Steinbeck, Don’t Be Bad, is a heartbreaking reminder that we won’t see any more films by Caligari, but it’s also a testament to his unique brand of sociopolitical filmmaking. I had the chance to attend a screening of the film in New York and listening to Mastandrea’s sincere admiration and love for Caligari and the film were awe-inspiring.

Read the interview after the jump...

Valerio Mastandrea

Valerio Mastandrea

JOSE: It's uncommon to see "love stories" that aren't about romantic love, and in Don't Be Bad, we see how the love between Cesare and Vittorio is as epic as those we see in classic romances. What would you say keeps filmmakers away from making films about this kind of love?

VALERIO MASTANDREA: What I can say is that if a filmmaker is able to not lose track of the grandness of cinema, he/she is able to deal with the subject of love and the infinite shades of feelings like no one else. Cinema is definitely the most appropriate tool to explore all this.

JOSE: There is something both Shakespearean and Biblical about the central relationship in the film, and we can detect a conflict of worldviews present. Are these men bound by fate, or can they exert free will? Was this something that Claudio spoke about in his own life?

VALERIO MASTANDREA: One of the conditions that characterize the individuals in the film is that they are creators of their own destiny, especially Vittorio in his choice of accepting the rules of society—getting a job, building a family. It is also true that one cannot disregard the context and its flaw in which these characters exist, not as an alibi, but as a fact. It is true that in those areas, sort of at edge of the world, it is more difficult to "don't be bad." Most of Claudio Caligari's life and career were exactly like this. For many years, his way of making films (as well as those of many others) had been cast aside by a ruthless business mentality. Claudio stood up to it. He suffered. He never compromised. And he made his unfortunately too few films freely.

Since you were on the set during the shooting, what aspects of production were the most challenging?

Our pre-production was really short. Because of Claudio's illness we only worked with him for two weeks in pre-production. Therefore, all the preparation happened directly on set each day. On this matter, I have to say that cinematography and the other departments were amazing! They all managed to bring together their ideas for each location in a timely fashion and with a unique efficiency.

With Claudio being ill during the production, did he ever give the crew specific instructions on how he wanted the film to be completed if he couldn't finish it?

He never gave us instructions in a direct way. He would talk about his work, letting us know and feel how this movie should be. He also really trusted his DOP and editor. Claudio knew that his life was coming to an end, but he didn't know it would happen so soon. He was already thinking about his next film.

You worked closely with the editor to compete the film. How many cuts would you say you did before deciding you had the one you wanted?

We worked on the film already edited by Claudio and only made two "radical" decisions on two scenes that he cut. In regards to the soundtrack, we search for the music and added it to the edited version. It was very difficult work—during the first weeks we were more influenced by what we thought Claudio would have wanted. But when it came down to making finals decisions, we managed to do so with confidence, knowing that he had always trusted us.If we were his guys before and during the production, we still would have been afterward. After all, we have always been his team and he knew it.

You were extraordinary in La prima cosa bella and have worked with some of the greatest contemporary Italian filmmakers. How was working with Claudio different? What would you say was the most valuable thing you learned from him as an actor?

Rarely have I had the opportunity of experiencing classic Italian cinema so intensely as I did on the set of The Scent of the Night (L'Odore della Notte). This is another thing I learned from Claudio—I learned something more about my love for cinema and how to make film. I learned the dignity and passion of bringing ideas forward. This is the greatest gift he has ever gave me, and gave to us all.

You were a philosophy student and mentioned how Claudio was one of the last philosopher filmmakers. Did your own background in philosophy help you bond with him? If so, in what ways?

I believe that there is a mistake on IMDB about my studies. I never took philosophy. I only went to university for two years and studied history and foreign languages. I need to have that corrected. I wouldn't know how to explain philosophy as it applies to cinema. To me, anything that provokes a thought and an emotion can be philosophical in the most superficial way. And cinema is exactly this: thought and action.

The film is very much about Pasolini, and you also played a part in Abel Ferrara's Pasolini (which I thought was terrific!). Would you say there is a renewed interest in his work?

I don't think that interest in Pasolini ever faded away. His clarity about the world in which he was living is still impossible to find in contemporary intellectuals. His way of getting to know a subject before speaking was unique. And I am pretty sure he didn't only tell us about his time, but also about the future, which is our present.

You called Claudio a "man made of cinema." What were some of the movies and filmmakers he talked about the most? Any specific films he made you watch?

I think it's very difficult to list them all. During the production of Don't Be Bad he used to refer to Ford, Houston, on through to Scorsese and Pasolini. Each frame brought him back to a specific director, a maestro, which Claudio honored. In his will he left me all his books and his films. I think he left this world convinced that I still have to learn a lot. And I think he was right.

What would an Oscar nomination mean for the film? And for you?

For the movie it would be a huge acknowledgment of the hard work that everyone did. For me it would be the impetus to keep believing that my job can gift everyone with dreams every once in a while.