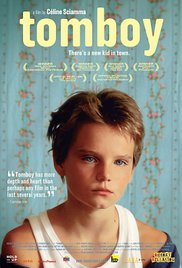

A young boy moves to a new town with his family. He's a goofball, a caring older sibling, and a shy kid. On his first day on the block, he runs into a girl and introduces himself as Mikael. She introduces herself as Lisa, and invites him to play a game of tag with her friends. Later, as he's taking a bath with his younger sister, his mother calls him Laure. She laughs and tells them: "Girls, get out of the bath!" It's almost 20 minutes into the movie before Celine Sciamma upends the expectations of her audience. In Tomboy, Sciamma examines how identity is constructed through performance in childhood, specifically in regards to gender.

A young boy moves to a new town with his family. He's a goofball, a caring older sibling, and a shy kid. On his first day on the block, he runs into a girl and introduces himself as Mikael. She introduces herself as Lisa, and invites him to play a game of tag with her friends. Later, as he's taking a bath with his younger sister, his mother calls him Laure. She laughs and tells them: "Girls, get out of the bath!" It's almost 20 minutes into the movie before Celine Sciamma upends the expectations of her audience. In Tomboy, Sciamma examines how identity is constructed through performance in childhood, specifically in regards to gender.

The main character of Sciamma's 2011 film is still in that period before hormones kick in when all kids are basically agender in appearance. What separates genders from each other is how they move and how they present themselves. As Mikael, the main character (the outstanding Zoe Heran) spends a great deal of time observing other boys. He's already got the slouch down, but a series of soccer games teach him more. He watches the boys strip off their shirts, swagger and spit. Later, in front of a mirror, Mikael strips off his own shirt to examine his body. He practices swaggering and spitting, and performs so well in front of his new friends that he attracts an admirer, Lisa (Jeanne Disson). These scenes of Mikael observing, retreating, practicing, and returning get more and more elaborate. Can he take off his shirt? Can he pee in the woods? Can he stuff a swimsuit convincingly? Each new social gathering presents a potentially devastating unmasking as well.

Celine Sciamma takes sensitive subject matter and treats it matter-of-factly. She contrasts scenes of Mikael and his friends with Laure and her family; though pronouns change, the person behind them does not. Still, as Sciamma's main character navigates these two worlds, the gendered expectations whirling around the child soon become apparent. Everything from childrens' rhymes to card games have genders attached to them, further complicating this gender presentation experimentation. When Laure's dual identity as Mikael is revealed, parents who had previously been understanding of their tomboy daughter balk at the potential public humiliation.

Despite the high stakes, Sciamma refuses to overdramatize Tomboy. Children in the film are both immediately accepting - in the case of the younger sister - and intolerably cruel - as with Mikael's friends, who choose to "test" his anatomy once Laure's mother bursts the bubble. Rather than showing a moralistic movie that pats itself on the back for its progressiveness, Celine Sciamma observes her main character's experiments as Mikael and Laure with the same unjudgemental empathy that she brought to Water Lilies. The end is positive, but vague as to whether the main character will continue as Mikael or Laure. As Sciamma explained in an interview with Film Independent,

I made it with several layers, so that a transsexual person can say 'that was my childhood' and so that an heterosexual woman can also say it. The movie creates bond. That’s something I’m proud of.

In Tomboy and Water Lilies, Celine Sciamma shows herself to be a director who tackles sensitive subjects of youths on the fringes with sympathy and honesty. Her final film would further explore these themes.

12/31: Girlhood - Celine Sciamma's latest looks at the relationships girls develop with each other in a contemporary girl's gang. (Amazon Prime)