Jose continues our new series Contrarian Corner in which team members who feel very off-consensus about a particular topic can work through it...

Jose continues our new series Contrarian Corner in which team members who feel very off-consensus about a particular topic can work through it...

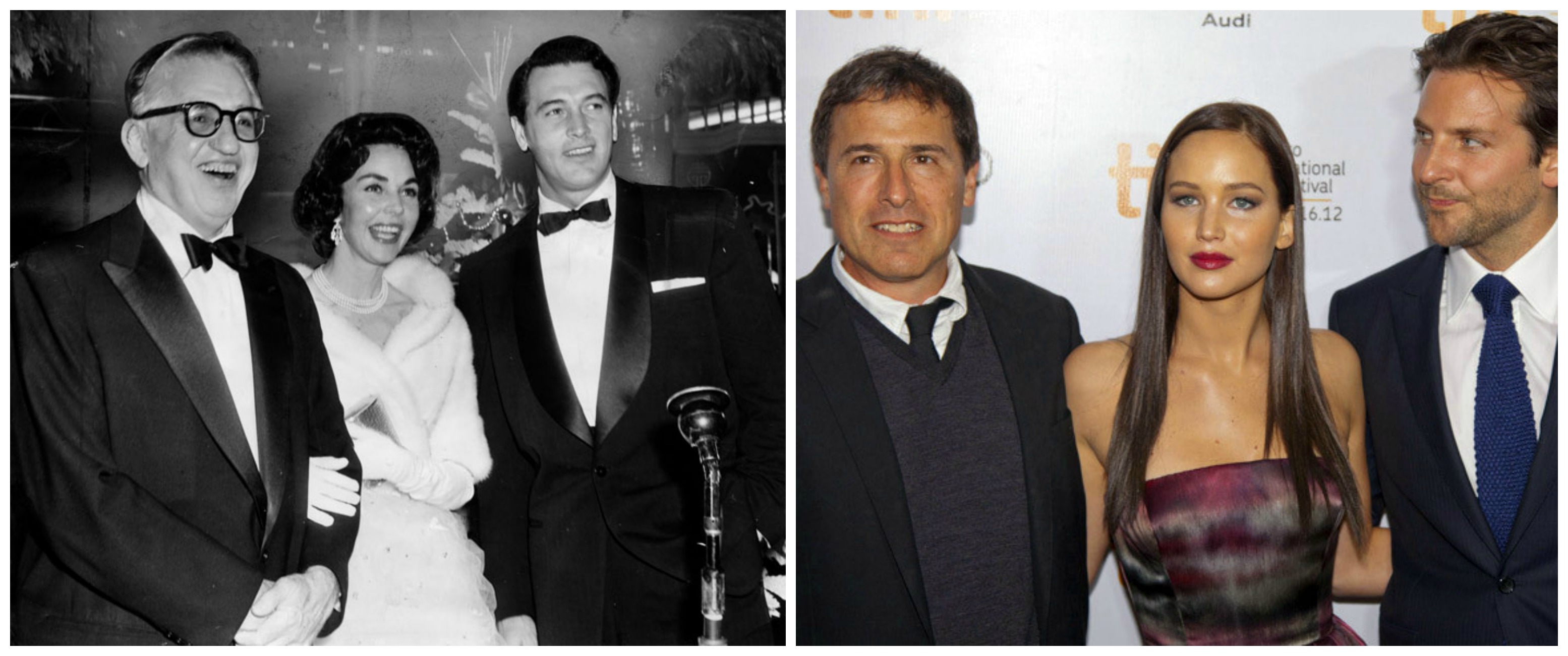

One of the most surreal moments in my life occurred when I was able to speak to Winona Ryder about Jennifer Lawrence. Like J.Law, Ryder became the “it girl” early during her career, and during the early 90s earned back-to-back Oscar nominations and critical/commercial adoration. Unlike J.Law, Ryder wasn’t able to make the most out of what fame and screen maturity had granted her, as she was denied serious parts because of her age. She looked “too young” to play “older parts”, and reached a point (i.e. her 30s) where she was “too old” to play younger parts. Perhaps because she has the good fortune of staying away from social media, Ms. Ryder was unaware of the constant criticism J.Law faces whenever she teams up with David O. Russell.

I don’t even know how old she is. I always thought she was the age of her characters”

Kudos to Ms. Ryder for reminding us that films are all about suspending our disbelief. [More...]

Deem it a combination of knowing too much about films before they’re released, anti-Russell sentiment, or plain old “kill your idols”-ness, but it was no surprise to see that once people started hearing about Joy, it was a throwback to the exact same complaints that we heard when Silver Linings Playbook and American Hustle came out. All of which boiled down to disliking the film for one of three options: Russell is a jerk, so his films must be boycotted; Russell is trying too hard to win awards by making Scorsese ripoffs; J.Law is too young to be playing anything other than action heroines.

Russell’s films with Lawrence therefore, are doomed with the curse of always being encountered with utterly lazy criticism.

What’s fascinating is how Russell and Lawrence react to these criticisms with mischievous self-awareness. Knowing their collaborations are reviewed using ready-to-fill forms, they have even announced they will be teaming up again in a film where she will play Robert De Niro’s mother. This endless outrage has sadly robbed us of engaged criticism and thoughtful conversation. Russell has, for better or for worse, become one of the most interesting postmodernist film historians of our times. Ever since reinventing himself with The Fighter (i.e. becoming an Oscar-hungry monster according to many) he has been delivering zany updates of some of Hollywood’s most cherished classic genres: The Fighter as inspirational sports film, Silver Linings Playbook a Capra-esque romantic comedy, American Hustle was The Sting, and with Joy he turns to the “woman’s picture” or the melodrama.

Taking the basics of the story of Miracle Mop inventor Joy Mangano, he has filtered and dissected the melodrama through two storytelling styles that have always been linked to the feminine: the fairy tale and the soap opera. He uses them to tell the story of a woman who against all odds became one of the most important inventors/entrepreneurs of the 20th century. When we first meet Joy, she is a mother trying to keep her household together; her mom (Virginia Madsen) prefers the safety of soaps to the harshness of the real world, her father (Robert De Niro), and ex-husband (Edgar Ramirez) are living in her basement in denial of their adulthood, her half-sister (Elisabeth Rohm) envies her, leaving only her grandmother (Diane Ladd) and best friend (Dascha Polanco) as her allies.

But this isn’t a story of victimhood or about a damsel-in-distress, as we hear young Joy (a lovely Isabella Crovetti-Cramp) establish, her special power is she doesn’t need a prince to come rescue her. She has her brain, and as the film unfolds we see her go from a slightly insecure, but determined, head of household, to a ferocious, but benevolent businesswoman seeking to impart justice in a world that wasn’t always particularly kind to her. As we follow her rise to the top, Russell uses every trope in the book to constantly remind us that the film isn’t a matter of fact biopic, but an homage to great films of Hollywood’s Golden Era in which grand female movie stars were the draw. Bette Davis, Dorothy Lamour, Olivia de Havilland, Jennifer Jones, Jennifer Lawrence

Bette Davis, Dorothy Lamour, Olivia de Havilland, Jennifer Jones, Jennifer Lawrence

Curiously, these films also featured bona fide movie stars in roles that saw them age through “movie magic”. In films like 1943’s Madame Curie, we see 39-year-old Greer Garson play Marie Curie from her mid-30s all the way to age 63, as she celebrated the quarter century anniversary of the discovery of radius. In Mother Wore Tights, a 31-year-old Betty Grable was aged over 40 years to play vaudeville star Myrtle McKinley. Olivia de Havilland famously won a Best Actress Oscar at age 30 for playing the tragic Miss Josephine Norris in To Each His Own, in a role which towards the end of the film saw her play mother to John Lund, who was five years her senior.

While arguably these conventions are old fashioned and for the most part seem politically incorrect for the world that we live in, they don’t diminish the power of the performances. De Havilland will always be moving, Curie will always be majestic, and in films like Mr. Skeffington and The Old Maid, both of which saw her don white wigs and wrinkles, Bette Davis will never not impress. (outside of the Golden Age era Liz Taylor did it in Giant, Ash Wednesday and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, Kate Winslet in The Reader, Cicely Tyson in The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman, Julianne Moore in The Hours…) Why isn’t Lawrence allowed this too?

In Joy, Russell makes mention of a classic actress in particular, as TV executive Neil Walker (Bradley Cooper) explains the ropes of QVC to Joy, he compares himself to producer David O. Selznick, and tells her how he married Hollywood actress Jennifer Jones (Nathaniel pointed out the Oscar parallels between both Jennifers here). While Neil’s anecdote has more to do with romance and the ordinary meeting the extraordinary, it draws an undeniable creative parallel between Lawrence and her mentor, making it clear that more than anything else, Joy is an altar to the power of a classic female movie star (needless to say so, in Good Morning, Miss Dove, 36-year-old Jones was aged 40 years to play the title character as she looked back at her life).

But having Lawrence playing a Jones-type heroine isn’t enough for Russell, he understands that homage can only go so far, so what he does is that he grabs these tropes and subverts them by comparing them to real life moments in Lawrence’s professional career, which has been nothing if not quite admirable both artistically and commercially. There is a scene where Joy confronts a man who has tried to cheat her in business, and she explains that no men in California have treated her well, even if “we’re supposed to be in business together”, one can practically imagine Lawrence engaging in similar conversations as she negotiates her contracts following the Sony hack, which helped her become one of the most outspoken figures when it comes to pay equality.

When Joy’s patents are in peril of being stolen, we see her reclaim them as her own, similarly to how Lawrence approached her leaked picture scandal by reminding us all that to take part in diffusion of stolen property is to be a thief. That Lawrence has acted with such maturity at such a young age, more than merits why in latter scenes of Joy, we see her as a wise figure helping younger women achieve their dreams. In real life, Joy Mangano has patented hundreds of products and has aided female inventors, so it makes sense that Russell also envisions Lawrence as a Hollywood doyenne, fighting to protect the rights of other women in the industry. That he shoots these scenes as if they were part of The Godfather and Citizen Kane, with Lawrence playing Don Corleone and Charles Foster Kane is deliciously subversive, and has for the most part remained undiscussed.

Joy is by no means a perfect film, but it contains ideas and themes that aren’t part of most mainstream cinema (quick, name the last movie you saw about a female inventor!). Erin Brockovich was perhaps the last time an American director decided to provide a superstar with a vehicle that celebrated both her star power and her thespian abilities, and as such, it’s a shame that the discussion has remained so obtuse. Despite her age, Lawrence is also a woman in Hollywood, so to deny her parts that should go to older actresses, is to put her in a position that would inevitably lead to filmmakers simply forgetting about her, or like they did with Ryder, having them put her aside as they waited for her to fit their preconceived notions of how she should look at a certain age.

Accusing Russell of aiding this problem might not be farfetched, but would he even want to do a film like Joy without the heroine he had in mind? Are we better off not having movies about women if they won’t star the women we think should be in them? By now, Lawrence has showed us that she has enough range to secure a long career in the industry, so should she quit in her mid twenties and/or only play action heroines or mutants while she “grows up” to play older women? Her self aware, mature work in Joy is proof that we’re better off having her in our screens, and as often as possible.

So let's bring back the conversation to the film. Granted, you severely dislike Russell and still think Lawrence is too young. Are there any other complaints you have about Joy? Do you think less of films in which actresses use "old age" makeup?