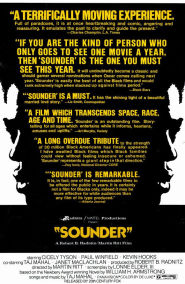

Andrew here, to continue The Film Experience’s celebration of Black History Month through the lens of the Oscars. Next up comes 1972's Sounder. It did not win any Oscars, and yet it is groundbreaking, of its own accord, and as an Oscar vehicle. The film, as well as its success at the time, is a miracle and one of the most impressive moments of Oscar’s celebration of black cinema.

Its greatest triumph in light of Oscar is the fact that it’s the first truly black film to be nominated for Best Picture. Sounder tells the story of a family of Black sharecroppers living in Louisiana during The Great Depression...

Times are hard and on an evening when spirits, and coffers, are especially low he steals some meat from some white land owners. And, although, that two-line synopsis might suggest an expected tale of an intrepid and indigent family dealing with the institutionalised racism of the era, Sounder (adapted from the superlative children’s novel of the same name). Except, unlike so many black films from then to now Sounder is less interested in examining the convergence of differing classes and is, instead, satisfied to focus with specificity on the quiet life of that black family.

Its nomination in the picture category may seem something of an afterthought in a year of The Godfather, Cabaret, Deliverance and The Emigrants. It’s the only of the picture nominees without a corresponding director nomination, adding to the semblance of its runner-up status. Add this to the fact that a plot description belies Sounder’s important adds to its forgotten status. But, to take a close look at Sounder and observe its deftness of focus, and surety of delivery only reveals it as worthy of its place among that impressive Best Picture line-up.

Sounder is a film above the love and tenacity of a family unit. This intent seems slight amidst the reaches of its best picture contemporaries until you stop to consider that simple act was an act of defiance for a film with a black cast in its time.

David Graham DuBois (former Black Panther spokesperson and professor of Afro-American studies and journalism at the University of Massachusetts) deftly sums up the import of Sounder by highlighting the cinematic landscape it emerges from.

“The Cottons, the Shafts, the Melindas, the Superflys and the Trouble Men all perpetuate these lies [that pain and suffering for blacks is borne lightly and that joy is derived from forever merry-making in wasteful sloveness]. This is why they are pushed before the movie-going audience. And this is why they "succeed." Overlayed with a thick coat- ing of carnal lust, violence, flashy clothes, expensive cars and unbelievable exploits-not reserved for black films- the deeper message of these films is insidious: black people are somehow less than human, i.e. their love is purely animal; their courage is a simple animal reflex against the threat of physical harm; their determination is operative only for the achieving of transient and meaningless goals. Family life does not exist for black people according to these films. The life of the streets, night clubs, poolhalls and sordid women is the source of our greatest joy. Our pain and suffering is a self-inflicted root.”

I’m not quite as dismissive of the Shafts and Trouble Men as DuBois but the consequence of a film like Sounder and its observations on black lives cannot be understated. More significantly was the response to it. Made for under a million dollars the film earned more than sixteen times its budget at the box-office becoming one of the 15 highest grossing films of the year. That was 1972 that Hollywood and producers should have realised that good films on black lives could make money, and yet, it seems it’s something that so few studios seem to acknowledge.

Sounder’s simplicity of spirit is its own badge of courage. The legend of the black film, especially in the face of injustices meted out to its characters, is one where audiences have come to expect a call to revolution to accompany each injustice. Sounder’s revolutionary act is having young David Lee become literate, taught by a kindly African American teacher. For the modern audience Sounder’s quietude may seem tame and yet that’s the beauty of it. What is beautiful about Sounder is the very fact that its blackness is not its most distinguishing feature. Not because the blackness of its story is shrouded, but because in developing a specific family’s tale of hardship Sounder is disinterested in selling an image of a specific “type” of blackness and becomes that much more successful at achieving universality for the very way its characters feel pain, hurt and joy like any human.

The third act return of the family’s patriarch is a mostly wordless sequence playing out against the family’s field that sees the Oscar nominated pair of Cicely Tyson and Paul Winfield asked to do nothing but showcase their love for each other. It’s a sequence that becomes affecting just because of the brilliance of those two actors and Martin Ritt’s uncomplicated but effective direction. Tyson and Winfield became the first pair of black actors to be nominated for Actor and Actress Oscars from the same film. Lonne Elder III became the first black writer nominated for an Oscar (that same year Suzanne de Passe was nominated for writing Lady Sings the Blues). Sounder also features music from blues musician Taj Mahal. Power to Martin Ritt (one of the era's forgotten, excellent directors) for his skilfull handling of the material. Whenever stories about the marginalised are told I think about the eterna question of who should be telling those stories. Might Sounder benefit from a black filmmaker at the helm? I don't know. Perhaps. And, then, perhaps not.

As it is, the issues with Sounder amount to minutiae. A larger glimpse into Tyson's Rebecca would have been lovely. And, the film is particularly guilty of not quite justifying its title the way the novel is. But, who cares? Is the fact that Sounder fated to a history as a nominee and not a winner indicative of a perverse blueprint of the Academy recognising black films for wins only on their own terms? I would not agree. The very state of awards means that only one can win. The significance of a nomination has become diluted over the years, but Sounder’s quartet of well deserved Oscar nominations fill me with joy.

A few months ago a friend pointed me towards this DVD box-set featuring timeless cassic films for the family, and I was ambivalent about the idea. As he rightly point out, if Sounder should be on a boxset it should be on one celebrating Cicely Tyson. But, then, what other way to introduce this fantastic but forgotten film to middle class viewers (who are not Oscar enthusiasts)? Any way that Sounder gets seen is great for me. 43 years after its debut it is still the paramount portrait of the life of a black family. That might be an indication of the great distance we are still to travel for black cinema, but then, Sounder is a high bar to scale.