We were just wrapping up Black History Month when I heard from longtime reader/commenter Philip Harville who wanted to discuss Monster's Ball (2001). I wasn't touching that one with a ten foot pole (!) but here's Philip with a guest column on this perpetual hot potato. -Editor

We were just wrapping up Black History Month when I heard from longtime reader/commenter Philip Harville who wanted to discuss Monster's Ball (2001). I wasn't touching that one with a ten foot pole (!) but here's Philip with a guest column on this perpetual hot potato. -Editor

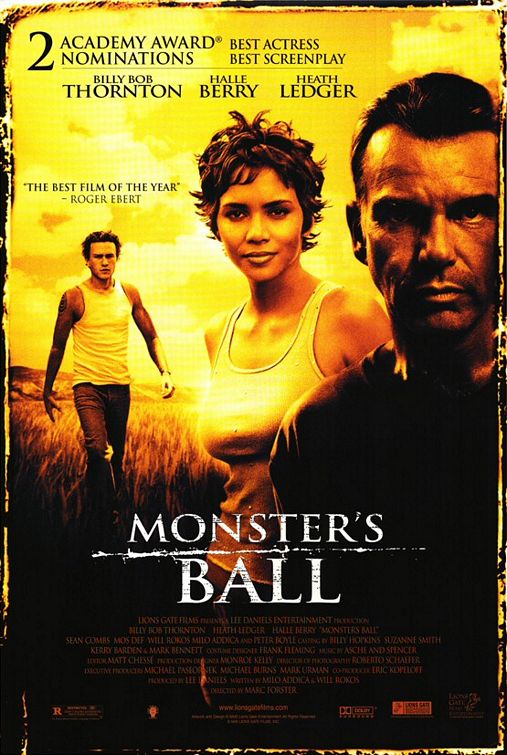

As we know, black films are hard to come by and good black films can be even harder to come by. This raises the question of what exactly a black film is. Is it simply a film that focuses on black characters? Or do we need to also have a black crew telling the story? The conversations unraveling from that thought are endless, but watching a certain film recently got me thinking. Monster’s Ball’s Leticia (Halle Berry) really suffers from a white male perspective behind the camera. The film gained a wide audience crowning Halle Berry as the first black woman to win the Best Actress Oscar, but did it create the conversation it should have? Good black films aren’t exactly churned out with the frequency of superhero movies (or Tyler Perry movies), so a flawed complicated film is a gift in its own right.

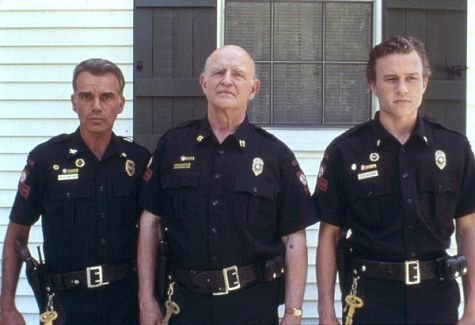

The film isn’t set in a definitive year, though it seems to be in a time where lynching and protesting were out of style, and casual racism has become the norm. We see the generational divide on the issue between the three males in the central family. [More...]

The grandfather Buck (Peter Boyle) is clearly not having it, referring to their black neighbors as “porch monkeys” and even using the N-word, whereas young Sonny (Heath Ledger) befriends them. Our protagonist Hank (Billy Bob Thornton) is caught in the middle, torn between the way he was raised and changing as society does. Pressured by his father, Hank threatens the black children to stay off of his property, even though they were only there out of Sonny’s permission. The boys are afraid of Hank, who is a cop, which speaks to the mistrust of police, which still goes on today. Race is presented in a fairly interesting manner, but the misogyny in the film is elementary, with constant remarks such as “you’re like a goddamn woman” and “you remind me of your mother,” among others. Masculinity is endorsed as the highest value. In a rare moment when the characters are discussing something that isn't racist or misogynistic, Buck tells Hank he’s a fool for quitting his job as a police officer and buying a gas station. “I woulda stuck to what I know best,” he says. The script essentially has flashing neon signs pointing towards Buck’s ignorance, telling the audience he has the exact mindset you should avoid. Yet, the film, however well intentioned manages to be problematic in its own way.

Those that have studied film know the tropes black women almost always fell into in the past (and sometimes still today) from the mammy to the jezebel to the welfare queen—stock black characters that were usually just used to further the white characters. While Leticia is a tad more three-dimensional she is never truly given a voice. In fact, none of the women in the film have much agency. Almost every woman that appears on screen is used sexually at some point. The prostitutes Hank and Sonny pay are only nude catalysts for the men to vocalize their problems. Even Leticia winds up in a sex scene that, while believable in terms of the narrative and characters, is so long and gratuitous, you can't help but question the male gaze and the motives behind the direction. Would this scene have been played differently if the film had a female director? Would this scene play out as it does if the actress herself wasn't a famous sex symbol?

Questionable objectification aside, we honestly learn little about Leticia. Everything we know is in relation to the men in her life—her husband, her son, her boss, Hank. Though we can understand why Leticia leans on Hank with all she is dealing with, he is interested in her, at least in the beginning, because he feels guilt; guilt for his son, who was so open and accepting, having committed suicide. And guilt for his father, who is the antithesis of accepting. Maybe he pursues Leticia to forgive himself? Feelings develop, but the white guilt leads to savior-ism detracts from the relationship. It starts harmlessly with rides to work, then fixing up his son's car and gifting it to her. Eventually Leticia moves in with Hank when she's evicted from her own home. These are generous gestures on the surface but they do turn Leticia as a character into a charity case and give Hank the arc, and the redemption, as he's able to turn against the old hateful ways.

Questionable objectification aside, we honestly learn little about Leticia. Everything we know is in relation to the men in her life—her husband, her son, her boss, Hank. Though we can understand why Leticia leans on Hank with all she is dealing with, he is interested in her, at least in the beginning, because he feels guilt; guilt for his son, who was so open and accepting, having committed suicide. And guilt for his father, who is the antithesis of accepting. Maybe he pursues Leticia to forgive himself? Feelings develop, but the white guilt leads to savior-ism detracts from the relationship. It starts harmlessly with rides to work, then fixing up his son's car and gifting it to her. Eventually Leticia moves in with Hank when she's evicted from her own home. These are generous gestures on the surface but they do turn Leticia as a character into a charity case and give Hank the arc, and the redemption, as he's able to turn against the old hateful ways.

Monster’s Ball seems to fetishize the black woman without even realizing it. Towards the end of the film, just before he services Leticia in bed, Hank tells her he wants to take care of her. She replies with “good, because I really need to be taken care of.” Leticia embracing her helplessness is a bit unsettling, not because it isn’t complex or interesting, but because of the broader implications. “you too can stop being racist if you help a poor black woman.” Perhaps this is just a transitional phase for both Hank and Leticia, helping each other cope along the way. And maybe director Marc Forster and writers Milo Addica and Will Rokos were well aware of these uncomfortable ideas. For me, what really nailed the coffin shut was the unbearably cheap metaphor of Hank having an obsession with chocolate ice cream.

The problem with the “white hero saves the black person” narrative is not that it happens, but that we see it so often without other viewpoints. White savior-ism is no stranger to the Academy, with films like The Blind Side and The Help recently nominated for Best Picture. It isn’t the job of one film or character -- not even a film that accidentally becomes a historical showbiz talking point like Monster's Ball -- to represent all minorities, but when other representation is lacking it's more upsetting. Six black women have won supporting actress Oscars, and the winning roles are as follows: a maid, a phony psychic, a sassy singer, an abusive mother, a maid, and a slave. Sure, all of these characters had depth and heart (yes, even Mo’Nique in Precious), but they still fill racial stereotypes. The goal is not to erase truth or black history; honoring the help that served white folks or the slaves that suffered years of subhuman treatment is important, but if that's all we have, it's troubling. Halle Berry, the first and only black Best Actress winner thus far, won for a role that falls somewhere between a jezebel and welfare queen (some may even say abusive mother). Does this make the character more interesting or does Leticia simply become an amalgamation of several stereotypes?

At the end of the day, we simply need to be seeing a black woman play a professor who gets early onset alzheimers, or a socialite who loses everything and suffers a mental breakdown, or a depressed widow who wants to win a dance competition, or an innocent ballerina finding her dark side, and so on. Does this begin with more black and female screenwriters and/or directors? Maybe it does, maybe it doesn’t. Being colorblind is not necessary, but we must allow black characters to live as more than just their race, or what’s expected of them, before we see true diversity in film.