Michael C. returning for review duties.

Michael C. returning for review duties.

Science fiction stories have wondered for ages if people will accept technology that simulates human behavior, but honestly, it probably won’t be much of a struggle. The robots will win in a walk. The urge to empathize is hard wired into the human psyche. I can remember when I was young, watching other kids develop deep emotional bonds to plastic eggs with crude blinking pixel displays just because they were called digital pets. What chance does the species have when a robot arrives with supermodel looks and a subtle range of emotion, one that can take you by the hand, gaze deeply into your eyes and say, “I love you” like it means it? Game over, man...

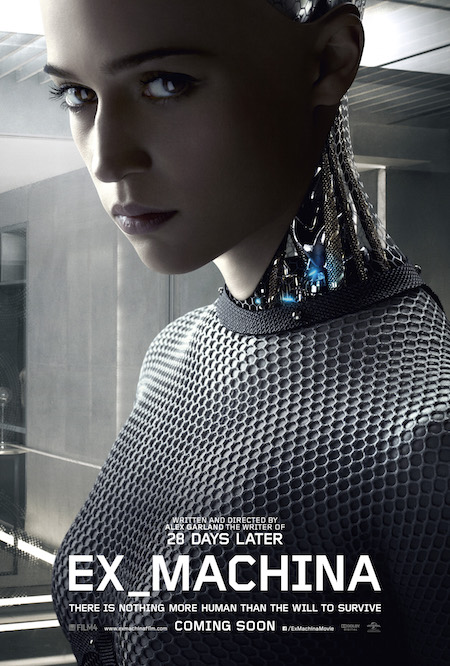

Nathan, the mysterious tech mogul at the center of Alex Garland’s engrossing Ex Machina, is certainly confident that Ava, his latest AI creation, will be tough for people to resist, particularly straight men. The famous Turing Test involves a machine that is indistinguishable from a human, but Nathan doesn’t attempt to hide the fact that Ava is an artificial person. “She” has the near-perfect face of actress Alicia Vikander but also has a skull of gleaming exposed silver and a see through torso that reveals coils of wires and glowing electronics. When Nathan brings in Caleb, a gifted coder who works for his company, as a test subject the idea isn’t to trick him into loving a machine, but to show him her reality upfront to see if the two of them will form a connection anyway. Judging by Caleb’s reaction to Ava with her features that look like they have been designed by an algorithm to be as appealing as possible, it looks like it will be an easy win, although we quickly surmise that there is much more to this experiment than Nathan is letting on.

Set in a vague, not-too-distant future, Ex Machina is structured around an escalating series of encounters between Caleb and Ava orchestrated by Nathan at his expansive private estate. The tension is elevated by the fact that 99% of the film takes place at the single location with only these three characters (plus Nathan’s obedient maid floating around the periphery). Ex Machina aspires to the realm of compressed battle-of-wits dramas like Anthony Shaffer’s Sleuth, where the plot relies on peeling back the secret motivations of the players in this three-way chess match. Eventually the twists start arriving, many we suspect, some we may not, but unlike lesser thrillers where it feels as if the writer started with the big twist and worked backwards, Ex Machina plays as if Garland began with his ideas first. The result is some top-notch sci-fi with big ideas nestled in a polished, Kubrick-y production design, all low-level lighting and unsettlingly clean surfaces. When the plot is unwound and all the cards have been turned over it holds together. Garland thought it through and the characters were worth the patience and attention the film asked of us.

Domnhall Gleeson and Alicia Vikander are marvelous as Caleb and Ava. Him, naive but also clever and resourceful, her, balanced precariously in the grey zone between simulated humanity and very real consciousness. That praise having been said, the movie belongs to Oscar Isaac’s Nathan from the first time we see him with his shaved head and bushy madman beard. We immediately peg him as a crackpot, because of the slightly unhinged aura he gives off and because movies have trained us to be wary of the scientist who flees to his secluded lair to play god. Isaac runs in the opposite direction, playing up the character's sanity. His Nathan is a casual megalomaniac, kooky around the edges but lucid when explaining himself and sharp at reading those around him. It makes us second-guess our initial assumption and we lean in to try to suss out if this guy is for real.

If Ex Machina lands a few steps shy of new classic status it's because while it is unfailingly absorbing it never crashes through to riveting or shattering. The exchanges between Caleb and Ava can be subtle to a fault and their dialogue could have used sharpening to achieve the spellbinding effect for which they are aiming. Many of Ex Machina’s best moments play like eccentric doodles around the edges of Garland's ultra-precise directorial vision, like when Isaac busts out a bonkers synchronized dance with his maid out of nowhere. More such beats would’ve been welcome.

Artificial intelligence can serve as a handy metaphor for any theme a writer wishes to explore, be it as a stand in for oppressed minorities or as a distorted reflection of our own humanity. Garland looks at Ava and marvels at the way the human race is sprinting towards its own obsolescence. Caleb quotes Oppenheimer’s "Now, I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds" to Nathan who is blasé about his role in hastening the irrelevance of his species, as if anyone capable of doing so has no choice but to proceed, consequences be damned.

More interesting still, is the film’s sly gender commentary, which isn’t limited to the obvious symbolic value of a Dr. Frankenstein who creates a woman to be his personal property. Ex Machina is equally damning in its portrayal of Caleb, the ostensible “nice guy” who cares for this simulated woman to the point of falling in love with her without it ever occurring to him that she might be a creature with thoughts and agency that exists outside out his conception of her as a prize to be won.

I could go on, but this already goes to show that Ex Machina does what good sci-fi should do, which is to reverberate in the imagination with different readings long after the movie is over. It is all too rare a specimen to find occupying multiplex screens these days.

Grade: B+