Tim here. It's been a good few weeks for animated short films about the fluctuating nature of memories and the complex relationship we have with the past: the warm glow has hardly faded from the online premiere of World of Tomorrow, and this week has seen the premiere on Vimeo of The Alchemist's Letter, written and directed by Carlos Andre Stevens, a Student Academy Award nominee for his 2008 debut, Toumai.

Tim here. It's been a good few weeks for animated short films about the fluctuating nature of memories and the complex relationship we have with the past: the warm glow has hardly faded from the online premiere of World of Tomorrow, and this week has seen the premiere on Vimeo of The Alchemist's Letter, written and directed by Carlos Andre Stevens, a Student Academy Award nominee for his 2008 debut, Toumai.

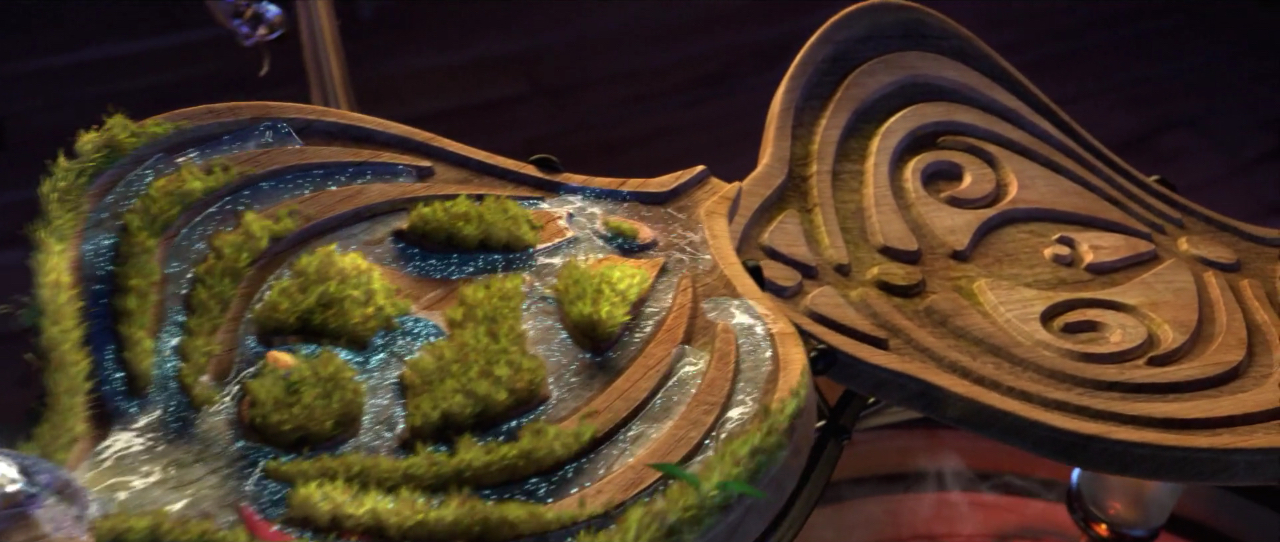

It's transparently a calling card for Stevens, an employee of commercial animation studio HouseSpecial -- that's a former division of Laika, some of whose designers and effects animators have hopped over to help guide the uncommonly lush and appropriately fussy look of the short -- but what a calling card! It's a brilliant little jeweled egg of a short, evocatively sketching out a whole human life in less than five and a half minutes, and doing it through some utterly beautiful design and animation.

Crouched inside a framing narrative delivered by Eloise Webb that, admittedly, runs the risk of being a bit repetitive, The Alchemist's Letter finds a young man returning to the home of his late father, an alchemist, whom he hadn't seen or spoken to in many years. He arrives with a letter in hand, in which the alchemist confesses his guilt over pursuing his experiments at the expense of his family. The letter is read in the voice of John Hurt, which proves absolutely essential: his craggy voice, with its irascible warmth, is tailor-made for a bedtime story (who else besides me still thinks of Hurt's turn in the 1987 series The Storyteller with particular fondness?), which is basically what The Alchemist's Letter is. It's an attempt to explain in simple language the painful realities of life.

More specifically, it's a metaphor about sacrificing the things that matter for the things that seem to be important. The alchemist's discovery that the secret to turning base metal into gold is to feed it his most beautiful memories is a visual conceit, but it also sets up a moral lesson with the concise clarity that only a fairy tale can achieve. This man decided that his work was more important than his past and his identity as a person; and so he ended his life with nothing left of himself. Nothing could be more blunt, but as related in Hurt's soft tones, it feels far more nuanced and emotionally real than just stating it outright.

That being said, purely as a visual conceit, it's a miraculous one. Rendering the alchemist's memories as little shadowboxes dissolving into energy, the film glides restlessly along a marvelous Rube Goldberg machine of smooth, rounded lines, which give it a steady, flowing feeling that's matched well by Stevens's artificial camera, never pausing but also flying along and through the finely-rendered details of the alchemist's workshop. Both in terms of the frame and the objects within the frame, The Alchemist's Letter is constantly in motion, inexorable and unstoppable visually as in the personal tragedy that it documents without being able to slow it down. The only weak link anywhere here is in the design of the human characters, which is thoroughly unexceptional; CGI people tend to look like all other CGI people, and given the beautiful, sorrowful details of every individual piece of the movie, the blandness of the humans robs it of some of its mythic loveliness.

But that's a sheer, unmitigated nitpick. The Alchemist's Letter is glistening and sleek and easy to get lost in; and it is deceptively sad and stern in its understated feeling of desolate loss. The fates of short films are impossible to predict, but in a just world, this will be seen by more than just the small and self-selecting population of short animation buffs. And it would be a great tragedy if this doesn't do wonderful things for Stevens's future career; he's absolutely earned it.