Our friend Diana Drumm is in Cannes and will be sending a few reviews our way. First up, Todd Haynes hotly anticipated Carol... (note: this review contains a couple of spoilers for those who haven't read the book)

Our friend Diana Drumm is in Cannes and will be sending a few reviews our way. First up, Todd Haynes hotly anticipated Carol... (note: this review contains a couple of spoilers for those who haven't read the book)

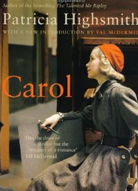

Within a year of publication, Patricia Highsmith’s first novel “Strangers on a Train” became a seminal Hitchcock thriller. After half a century, her second novel “The Price of Salt” (published under the pseudonym of Claire Morgan) is now a Todd Haynes romantic drama (under the succinct title Carol). Whereas the former concerns two male strangers duplicitous in murder, the latter is about two women finding love in constrictive 1952 New York City. Turning the pulp novel into a palpable parable, Carol is a master stroke in Haynes’s 21st century oeuvre (Far from Heaven, Mildred Pierce, et al.), and harkens back to the pressurized strength of Safe and the sexual fluidity of Velvet Goldmine - both capturing and throwing off the starched restrictiveness of postwar America, and deftly upgrading the melodrama with social relevance.

Inspired by Highsmith’s own stint at Macy’s (and her affair with Philadelphia socialite Virginia Kent Catherwood), 20-something shopgirl Therese Belivet (Rooney Mara) waits on and is struck by elegant “blondish woman in a fur coat” Carol Aird (Cate Blanchett). A friendship builds between the two, to the jealousy of Therese’s huffy square boyfriend (Jake Lacy), who dismisses it as schoolgirl crush, and the consternation of Carol’s matinee-handsome, soon-to-be ex-husband (Kyle Chandler), who uses it as ammunition in their ongoing divorce negotiations. [More]

While the men suspect the two of wayward lust, Therese and Carol actually tumble into love, a consuming, spiritual, kindred love. One not so much spoken as revealed through pauses pregnant with heart-wrenching glances. To the outside world, they remain era-appropriate discrete. So inconspicuous in fact that their conversations are constantly interrupted by unknowing meddlesome males, middling sorts ranging from salesmen to acquaintances, entitled to the women’s attention at seemingly all times even while the two are obviously in deep private conversation. As Carol’s longtime friend and former lover (Sarah Paulson) points out, the Aird marriage consisted of ten years of Mr. Aird stomping Carol’s individuality out while forcing himself in as Carol’s identifying point of reference - “your wife” - rather than a mutual partnership.

In Carol, male entitlement is almost as rampant as the Haynes-characteristic smatterings of 1950s cultural cues (President-Elect Eisenhower on both tv screen and radio, Perry Como’s Silver Bells plays, luscious furs on top of full waist-fitted skirts, etc.). While Blanchett’s Carol is styled with a blonde bob and Grace Kelly-esque accoutrements, Mara’s Therese transitions from mousy Jean Simmons into a young Audrey Hepburn-meets-Elizabeth Taylor type as their relationship develops and she comes into her own. But then the third act shifts into something rather extraordinarily timeless as Carol also comes into her own.

In the face of losing both custody of her daughter and the woman she loves, along with a respectable reputation, Carol makes a choice to stand for herself, not just for her or Therese’s sake, but for that of her daughter, movingly stating to her ex and their aghast lawyers, “What use am I to her if I’m living against my own grain?” A courageous coming out by today’s standards, even more remarkable and laudable in the context of 1952 America, two years after the official start of McCarthy’s “lavender scare” and a year before Eisenhower signed Executive Order 10450 (which allowed federal employees to be fired for “sexual perversion”).

And while Haynes masterfully sets the scenes with sumptuous slow pans, long take close-ups and a sweeping score, it’s Blanchett and Mara’s performances that turn this from a great period drama into a masterpiece. Through subtle looks, glances and physicality, Blanchett’s joie-de-vivre meets Mara’s imploring timidity to blossom into one of the most satisfyingly heart-wrenching, bordering on misery porn, romances in years.

While it’s easy to draw comparisons between this and 2013 Palme D’Or winner Blue Is The Warmest Color (lesbian love story performed by incredibly-abled actresses under a debatable male gaze), Carol is just as akin to the “women’s pictures” of George Cukor and Douglas Sirk. As Carol writes to Therese, “I do the only thing I can, I release you,” it’s hard not to think of Marguerite’s self-sacrifice for Armand in Cukor’s Camille. And similarly, with Carol’s custody battles, one is drawn to remembering the pull between motherhood and romance for glamor-stricken Lora Meredith in Sirk’s Imitation of Life. Those pictured ended in tuberculosis-ridden tragedy and fractured mother-daughter relationships, but Carol ends without immediate death or destruction. It stands as a much-needed revitalization of classic melodrama.

Grade: A