David looks back on the biggest cinematic year of one of cinema's most glamorous stars...

The thrill of this moment keeps me from saying what I really feel. I can only say thank you with all my heart to all who made this possible for me. Thank you.

Grace Kelly’s surprise Oscar win on 30 March, 1955, was the belated cherry on top of an incredible year by any actress’ standards, and certainly the busiest and most successful of Kelly’s ultimately brief Hollywood career. The basic narrative is now one of legend: the young, popular new star caught the attentions of the Academy over the established older performer; in this case, despite only being seven years older, Judy Garland. Hollywood gossip columnist Hedda Hopper said it was a matter of just 6 votes. If you believe her, than it's probably the closest Best Actress race ever, outside of the 1968 Hepburn-Streisand tie.

Grace Kelly’s surprise Oscar win on 30 March, 1955, was the belated cherry on top of an incredible year by any actress’ standards, and certainly the busiest and most successful of Kelly’s ultimately brief Hollywood career. The basic narrative is now one of legend: the young, popular new star caught the attentions of the Academy over the established older performer; in this case, despite only being seven years older, Judy Garland. Hollywood gossip columnist Hedda Hopper said it was a matter of just 6 votes. If you believe her, than it's probably the closest Best Actress race ever, outside of the 1968 Hepburn-Streisand tie.

History has decided that Grace Kelly didn’t deserve it. History may be right.

But at the time, there seemed to be no more fitting capper to Kelly’s incredible year than this reward, one received in such gracious form. In 1954, she starred in 5 films – almost half of her entire cinematic catalogue and a ubiquity comparable to the likes of Julia Roberts in 1990, or Jennifer Lawrence in 2012. While Princess Grace has been mythologised like few other Hollywood stars, the real story is a far more complex one than the romantic image allows. But that, of course, is the Hollywood machine for you. [More...]

The irony was that the studio she was signed to, MGM, had no real sense of the worth of the woman they had on their books. Though she had an Oscar nomination for Mogambo under her belt and had caught the eye of Alfred Hitchcock, MGM didn’t know what to do with Grace as a performer. On the record, a Metro publicist said to a journalist: “I don’t understand all the excitement about this girl.” They’d loaned her out to Paramount for Hitchcock’s Dial ‘M’ for Murder and Rear Window, and renewed that deal before Rear Window wrapped in January ‘54, signing Grace up for WWII drama The Bridges of Toko-Ri. The brief, expositionary role of Nancy, whose husband leaves her and their children to fight in Japan, barely seemed worthy of Grace’s star power, but it was essentially a trial run for director George Seaton, who would direct Grace to her Oscar in The Country Girl.

History and Grace herself largely dismiss The Bridges of Toko-Ri and the fifth 1954 Kelly movie, Green Fire, from this story, although the former was a hit with audiences and contributed to Grace’s profile, with her pre-title credit belying the size and unimportance of the role. Diabolical jungle adventure Green Fire was Grace’s only 1954 release with her home studio MGM, and demonstrated Metro’s growing crisis in the shifting moods of the decade. Already lumbered with months of developmental hell, the production had seen Eleanor Parker simply walk out and Robert Walker declare he’d rather retire than star in it. Lumbering their brightest star with such derided material pointed towards a studio that was losing its grip on the business, with their famously high overhead costs seeing them sink quicker than their rivals.

What they certainly weren’t counting on was Grace Kelly’s unexpected resilience and hard-nosed business sense. When they demanded she join the production of Green Fire instead of again joining Seaton at Paramount for The Country Girl, she had her agents send the MGM execs her New York address, nominally for their Christmas greetings. Kelly had never bought an L.A. home because her dreams lay on the Broadway stage, and she was more than prepared to turn her back on Hollywood if she was refused the opportunity to star in the film adaptation of Clifford Odets’ Tony-winning play. MGM compromised, and pushed back Green Fire’s production to accommodate her.

What they certainly weren’t counting on was Grace Kelly’s unexpected resilience and hard-nosed business sense. When they demanded she join the production of Green Fire instead of again joining Seaton at Paramount for The Country Girl, she had her agents send the MGM execs her New York address, nominally for their Christmas greetings. Kelly had never bought an L.A. home because her dreams lay on the Broadway stage, and she was more than prepared to turn her back on Hollywood if she was refused the opportunity to star in the film adaptation of Clifford Odets’ Tony-winning play. MGM compromised, and pushed back Green Fire’s production to accommodate her.

IF MGM thought that would quash the flames of Grace’s rebellion, they soon found themselves sorely mistaken. Having to regurgitate the turgid dialogue of Green Fire made Grace realise that she should never agree to sign to star in a film she hadn’t seen the script for, or simply didn’t want to appear in – and so, once Green Fire wrapped, a barbed game between Kelly and her studio began through the medium of the press. While she wanted to rejoin Hitchcock at Paramount for To Catch a Thief, they repeatedly announced her casting in a series of different pictures. She refused to play ball.

Annoyingly for MGM, the more assertive Grace was, the bigger her profile became. Dial ‘M’ for Murder opened in May, but word was already spreading about Grace’s work on her various sets, and in April, she was Life magazine’s cover story with the bold headline ‘Hollywood’s Hottest Property’. The brief article inside mentions her “determination”, a steel that really shouldn’t have so surprised the studio executives, especially with the sharp, narrowed eyes and hint of a smile in her cover photo. This wasn’t an aspect of her character Grace ever felt compelled to hide from anyone – “I was hired to be an actress, not a personality for the press,” she later said – but it was disguised by the aloofness that disinterest in her public image inferred, and her public reticence hid her private resolve.

Her steel led her to greater freedom in challenging MGM as her popularity with the public and the press blossomed throughout 1954 and beyond. Following in the ground-breaking footsteps of Olivia de Havilland – who successfully won her 1943 lawsuit against studio Warner Bros for extending her contract after suspensions – Grace Kelly was instrumental in finally dismantling the archaic studio star system for good, flatly refusing to bend to their wishes. This was her career, and she knew what suited her best.

However, The Country Girl is an outlier in Kelly’s career precisely because it doesn’t suit her; instead, it is perhaps the single role in her career chosen purely as a challenge, as opposed to a role that would contribute to her glamorous star image. In Georgie’s dedicated control of her husband’s career, it uses Grace’s backstage steeliness and resolve, and her bitter demeanour is worn into Georgie in a physical exaggeration of Grace’s real dissatisfactions with her life in Hollywood. Both spoken memories and a tragic flashback allude to Georgie as having a “a kind of nobility” about her, as if the film is designed to acknowledge Grace’s public character and erode it.

Georgie is introduced as an irascible and condescending woman, with a voice that cuts sharply through the confidence of the men around her. “What is that supposed to be,” she brusquely asks of Bernie’s (William Holden) polite manner, “homage to a lady?” While Grace’s physicality is stiff and often awkward, she uses her beauty to make Georgie’s eyes the focal point, distrustfully observing those around her or sorrowfully admitting her deception. She can’t entirely avoid brash overacting, with some dramatic scenes proving too theatrically flamboyant (not to mention the film treating her at one point like a monster looming out of the shadows), but for the most part, it’s a remarkably subdued and angsty performance, full of a sadness belying the actress’ years.

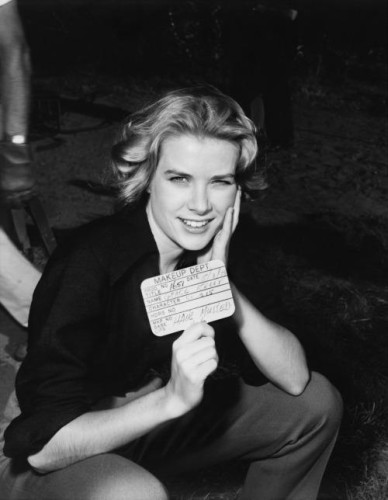

Grace and William Holden in The Country Girl

Grace and William Holden in The Country Girl

The Country Girl is far from a perfect film, hamstrung by its theatrical origins, the plain black-and-white cinematography and a story the dynamics of which never find the most rewarding angle on the character interaction. Kelly never got the chance to play a character of the complexity of Garland’s essentially similar role in A Star is Born, and she acknowledged this, later recalling to biographer Donald Spoto:

I remember thinking at the time, ‘Oh, if only I were five years older, I could do this so much better!’ And then, after I’d been married five years, I thought, ‘Well, I could certainly do The Country Girl better!’ And now, years later, perhaps it would be even better…’

Kelly, of course, only just reached the age Bing Crosby had been at the time of filming The Country Girl two years before her tragic death in 1982. She departed Hollywood in 1956 after only three further roles: To Catch a Thief in 1955, and The Swan and High Society in 1956. While Oscar watchers may have reason to dispute the result of the 1954 Best Actress race, The Country Girl’s cinematic importance cannot be underestimated both for what it meant for Kelly’s fight for performers’ independence in Hollywood, and what it meant for Kelly herself. It is the only cinematic record of what she had spent her life dreaming of: proper dramatic acting, mostly shorn of glamour, a character with a deeply problematic existence that could even vaguely reflect the turmoil going on inside Grace herself. If it is far from perfect, we’d do well to remember that neither was Grace Kelly herself.

Kelly, of course, only just reached the age Bing Crosby had been at the time of filming The Country Girl two years before her tragic death in 1982. She departed Hollywood in 1956 after only three further roles: To Catch a Thief in 1955, and The Swan and High Society in 1956. While Oscar watchers may have reason to dispute the result of the 1954 Best Actress race, The Country Girl’s cinematic importance cannot be underestimated both for what it meant for Kelly’s fight for performers’ independence in Hollywood, and what it meant for Kelly herself. It is the only cinematic record of what she had spent her life dreaming of: proper dramatic acting, mostly shorn of glamour, a character with a deeply problematic existence that could even vaguely reflect the turmoil going on inside Grace herself. If it is far from perfect, we’d do well to remember that neither was Grace Kelly herself.

previous 1954 pieces

- Audrey Hepburn's style in Sabrina

- Sabrina's Choice Linus or David?

- The Creature from the Black Lagoon B Movie classic

- Vintage Best ofs and Happenings

- The Best Actress Race via Life magazine covers

- Get Your Votes In on the Smackdown