Tim here. This past week marked the tenth anniversary of the festival premieres of two very different stop-motion animated features. We've recently chatted a bit about Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit, so other than reminding you that it exists, and it's still delightful a decade on, I will pass it by in silence. Instead, I want turn everybody's attention to Corpse Bride, or if you prefer - the boys in marketing clearly did - Tim Burton's Corpse Bride. The second movie's reputation has gone off in a very different direction over the last ten years: while Were-Rabbit remains a touchstone of sorts thanks to its iconic stars, I'll bet that a good number of you just thought, "Huh, Corpse Bride, I forgot all about that".

Tim here. This past week marked the tenth anniversary of the festival premieres of two very different stop-motion animated features. We've recently chatted a bit about Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit, so other than reminding you that it exists, and it's still delightful a decade on, I will pass it by in silence. Instead, I want turn everybody's attention to Corpse Bride, or if you prefer - the boys in marketing clearly did - Tim Burton's Corpse Bride. The second movie's reputation has gone off in a very different direction over the last ten years: while Were-Rabbit remains a touchstone of sorts thanks to its iconic stars, I'll bet that a good number of you just thought, "Huh, Corpse Bride, I forgot all about that".

That’s not unfair. Revisiting it for the first time in most of that same decade, I found it to be visually inventive, and dangerously rushed as a narrative: based on a Russian folk tale of a young man who accidentally weds a beautiful dead woman, the films never quite shakes the sketchy structure of a fable.

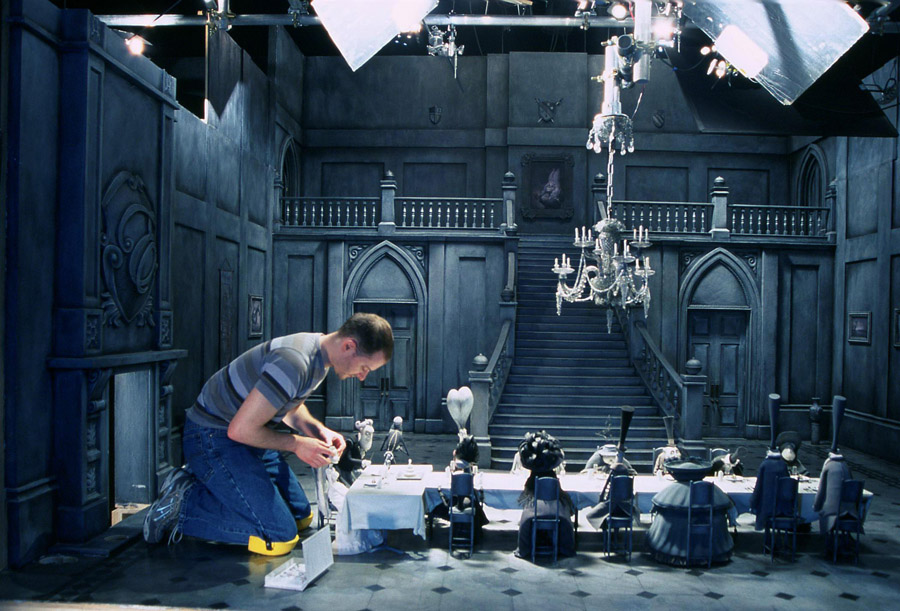

Mostly, it's a slight little slip of a thing, an exercise in letting former animator Burton get his feet wet in that medium alongside co-director Mike Johnson, and unworthy of much particularly energetic enthusiasm.

Certainly, the release a few years later of the stylistically similar but thoroughly more ambitious Coraline (directed by Henry Selick, the real genius behind Nightmare) has done nothing to make Corpse Bride any more essential. And yet here I go, asking you to maybe overlook all of that, because there’s something lovable beneath the film’s general triviality.

This is, for one thing, the closest we get to an actual Tim Burton film in the whole of the 2000s. It wasn’t nearly as clear in 2005 as it is in 2015 how thin the director was prepared to stretch his signature style: Planet of the Apes still looked like an aberration, and 2005’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory a mere miscalculation, rather than the template for several of Burton’s subsequent releases. On the backside of the unforgivable Alice in Uglyland, it’s nice to have a reminder that it wasn’t so long ago that Burton could still find something exciting and personal to draw him into a project.

For Corpse Bride is especially personal, full of obvious love from the filmmakers to their film like virtually nothing else in Burton’s late output. It has affection for its characters that warms up the pervasively blue and gray visuals (the afterlife being the only source of bright, saturated colors in the movie), and adds the necessary sense of lightnes to the decaying, zombified design.

t’s quintessential Burton, that is to say, blending the macabre and whimsical to charming rather than horrifying effect. I put it to you, readers, that the only 21st Century Burton films that completely work are this and Frankenweenie, the only two that are also stop-motion cartoons. And this is not a coincidence, I suspect. Breaking completely from reality is the director’s best trick for being able to explore feelings and characters from his distinctive personality without making it feel unpleasant and artificial.

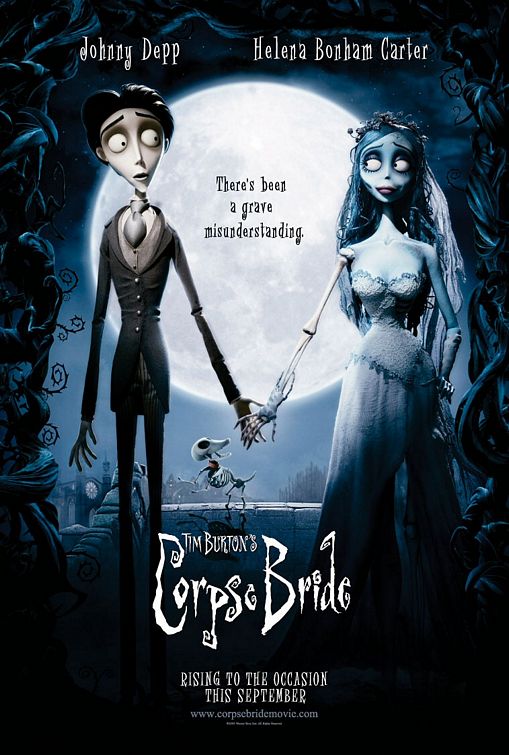

At any rate, it’s a sweet character piece. The director’s insistence on casting some combination of Johnny Depp and Helena Bonham Carter in every one of his films between 1999 and 2012 worked out better here than it ever would again: Depp’s dazzled innocence and Bonham Carter’s wistfulness cut against each other to provide a lovely bittersweet quality, and the filmmakers assembled a killer assembly of British character actors to back them up: Albert Finney, Joanna Lumley, Emily Watson, Tracey Ullman, and a small part for Christopher Lee, among others. The cast is enough to counteract the arch grotesquerie of the character designs, and leave us with the feeling of real people with hearts and souls maneuvering through the bizarre world and story, instead of being dropped into a menagerie of marketing-ready gothic perversions.

It is not, truthfully, likely to show up at the top of anybody’s Best of Tim Burton list. But I wouldn’t be at all shy about calling it the last one of his films that feels like he arrived ready to play 100%. How much comes from having a co-director, and how much the neat fit the material makes with his career-long preoccupations is impossible to say. Either way, the results are the same: a not so very old reminder of what makes Burton easy to love, instead of merely tolerable.