Team Experience is looking back on past Sundance winners since we aren't attending this year. Here's Tim on an animated indie honored early on...

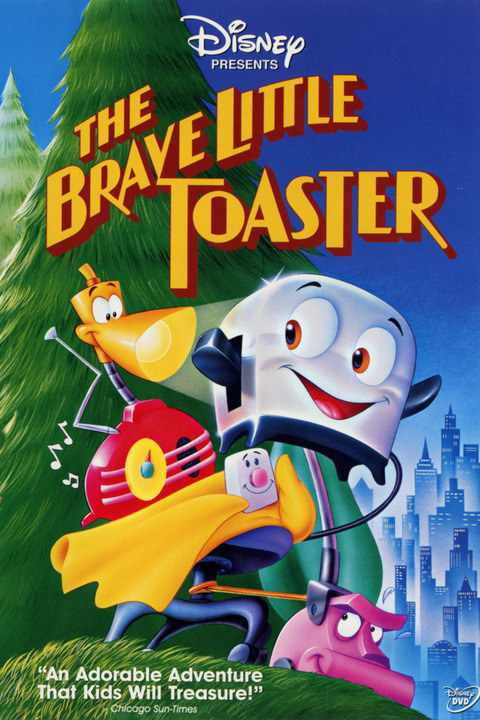

The Sundance Film Festival isn't necessarily what you think of as a hotbed of animation: even a simple animated feature takes a large budget and hundreds of hours to produce, and these are resources that indie movies are particularly noted for lacking. So when The Brave Little Toaster screened at Sundance in 1988, it was quite the aberration. Such an aberration, in fact, that it would be 13 years before another animated feature would show up at the festival. It was well-received, however: the film received a special citation from the jury at the festival's awards ceremony, and director Jerry Rees has maintained in later years that he was told that it was only a concern that awarding a cartoon would dilute the festival's prestige kept it from serious consideration for the grand prize.

The Sundance Film Festival isn't necessarily what you think of as a hotbed of animation: even a simple animated feature takes a large budget and hundreds of hours to produce, and these are resources that indie movies are particularly noted for lacking. So when The Brave Little Toaster screened at Sundance in 1988, it was quite the aberration. Such an aberration, in fact, that it would be 13 years before another animated feature would show up at the festival. It was well-received, however: the film received a special citation from the jury at the festival's awards ceremony, and director Jerry Rees has maintained in later years that he was told that it was only a concern that awarding a cartoon would dilute the festival's prestige kept it from serious consideration for the grand prize.

The film is a curious beast in every way possible. The project was initiated by Walt Disney Feature Animation – future Pixar guru John Lasseter had it in mind as a project while he was with Disney – and much of its financing came from Disney's coffers, and its talent Disney's staff, which would seem to be enough to disqualify it from "independent" status. [more...]

Yet it was made for an astonishingly small budget through Hyperion Animation (and I am sorry to say that with grown-up eyes, that low budget manifests itself in the animation), completely free of any influence from Disney. That, in turn, led to it enjoying a warped, weird tone and perspective that, even a quarter of a century later, doesn't quite resemble anything else. It's kind of like a kid's film, except with narrative ambiguities and shading that no kid could possibly be expected to pick up; it has the usual litany of musical numbers that, in the '80s, were the exclusive provenance of cartoons, but its songs go to some decidedly odd places in the orchestration, and utter bleakness in their staging – one number is sung by sentient cars as they're being crushed to death.

Above all, this is a profoundly strange variation on the most ordinary material of kiddie-flick adventure. It's basically The Incredible Journey with a twist: five abandoned appliances, including a toaster (Deanna Oliver), a desk lamp (Timothy Stack), a childish thermal blanket (Timothy E. Day), a radio (Jon Lovitz), and a vacuum cleaner (voiceover legend Thurl Ravenscroft, famed for his grrrrreat growling as Tony the Tiger, and for his jolly menace in musically declaring "You're a mean one, Mr. Grinch") go on a cross-country mission to find their absent owner, now a young adult in college. It's not at all unlike the scenarios for Pixar's later Toy Story films, or any of a great many "inanimate objects on a quest" cartoons.

It's also a borderline-hallucinogenic nightmare fantasy, with multiple sequences that drift into outright surrealism or horror imagery. Re-watching the film for the first time in an enormous number of years, I was frankly baffled by why, as a child, I was so unfazed by the movie, or why Disney, the most safe and conservative of all major studios, was so eager to market it to a child audience both on home video and on its ultra-sanitized Disney Channel. In fact, The Brave Little Toaster is very nearly an example of underground animation, often feeling like it had in mind an audience of college-age stoners rather than cartoon-loving eight-year-olds. It takes place in a fluctuating, arbitrary world marked by random cruelty and a constant fear of death, all offset by the bright colors and round shapes in a perverse, ironic way.

Viewed in that light, its presence and success at Sundance is perfectly rational. Calling The Brave Little Toaster "transgressive" would be absurd on the face of it, particularly given that it's almost exclusively a nostalgia product at this point in time. But there's no way around how much raw, nervous energy the film puts out, and how eagerly it perpetrates grim fates against its cute characters. It's a kiddie flick, a head movie, and a meditation on aging, obsolescence, and mortality all at once. A neat trick, not always completely successful or completely satisfying – the lawless chaos that reigns in place of consistent world building in particular makes it hard to process the movie as anything but a chain of vignettes – but it's a true original, one of the most intriguingly idiosyncratic animated films of an entire generation.