Tim here. Today is the 100th anniversary of the birth of director Jack Arnold, and if your response to hearing that name is a polite look of blank incomprehension, I wouldn't feel bad. Arnold's not exactly a household name and never has been, but you wouldn't want to imagine what classic sci-fi would look like without him. For a short time in the 1950s, Arnold was possibly the most admirable genre film director in Hollywood. I can't think of any better way to demonstrate how singularly iconic his work has been than to point out that he's the only filmmaker to have two different films named dropped in "Science Fiction/Double Feature", the opening number from The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

Tim here. Today is the 100th anniversary of the birth of director Jack Arnold, and if your response to hearing that name is a polite look of blank incomprehension, I wouldn't feel bad. Arnold's not exactly a household name and never has been, but you wouldn't want to imagine what classic sci-fi would look like without him. For a short time in the 1950s, Arnold was possibly the most admirable genre film director in Hollywood. I can't think of any better way to demonstrate how singularly iconic his work has been than to point out that he's the only filmmaker to have two different films named dropped in "Science Fiction/Double Feature", the opening number from The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

Undoubtedly the film for which Arnold remains best-known is the 1954 Creature from the Black Lagoon (and it's dimwitted first sequel, Revenge of the Creature, but it wouldn't be sporting to hold that against him), and it's fairly easy to argue that it's his best work, too.

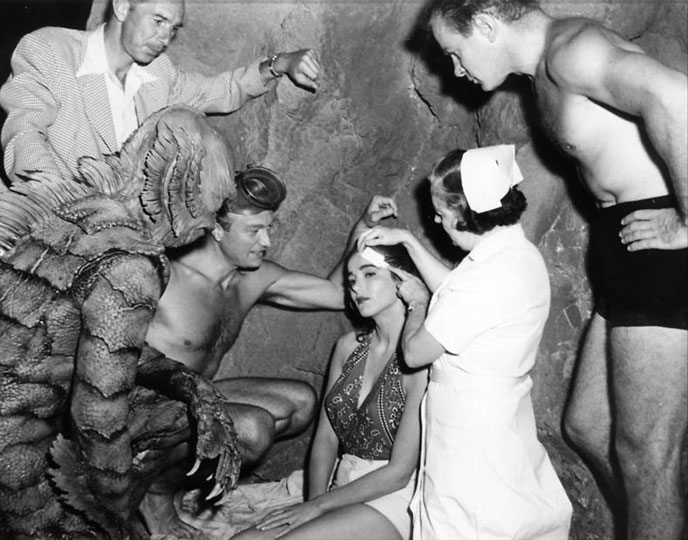

on the set of The Black Lagoon

on the set of The Black Lagoon

But however impressively he handled that last gasp of the Universal Horror machine, it's by no means his only noteworthy achievement...

Before he decamped for television right at the dawn of the 1960s, Arnold was a promiscuous dabbler in every kind of genre and style; his last couple of years in the cinema saw the release of the tawdry teensploitation flick High School Confidential and the Peter Sellers farce The Mouse That Roared. He worked with Orson Welles on 1957's Man in the Shadow and was an Oscar nominee in 1950 for the documentary With These Hands (he learned documentary filmmaking under the tutelage of no less an legend than Robert Flaherty).

He'll always be best-known and best-loved for his sci-fi/horror, though. The year before Creature, Arnold directed his first great lasting triumph, It Came from Outer Space. The film is in many ways just one more damn alien invasion film from an era lousy with the things (though, like Creature after it, it's one of the few films from the '50s 3D craze to use the gimmick in a largely thoughtful and effective way). But for a dubious genre, it's a definite stand-out, unnerving and creepy only only the most special '50s horror films managed to achieve. Not to mention its unusually humane ending (these aliens are no warmongers), for which we likely should credit screenwriter Harry Essex more than Arnold; yet it takes a great deal of skill from multiple people to invest such paint-by-numbers material with the soulfulness that allows that kind of genre-bending generosity to feel not merely earned, but necessary.

The year after Creature, Arnold oversaw Tarantula, one of the finest of the big bug movies; second, perhaps, only to the radioactive ant epic Them! By all means, the film gets crapped on: Rocky Horror throws shade at it, and it had the indignity to be a Mystery Science Theater 3000 subject. Still and all, if you account for the fact that it's a movie called Tarantula – for the reason you suppose it is, which is that it stars a tarantula the size of a house – it's an honest-to-goodness pleasure, and certainly better than a movie of its genre and market position had any reason to be. The California desert has rarely seemed as lonely and threateningly desolate as it does here, under Arnold's care; the film is aching with atmosphere throughout, which makes it easier to swallow the goofy premise when it makes itself known. Though by '50s sci-fi standards, it's not as goofy as all that, and the visual effects in Tarantula are thoroughly impressive for its era and budget.

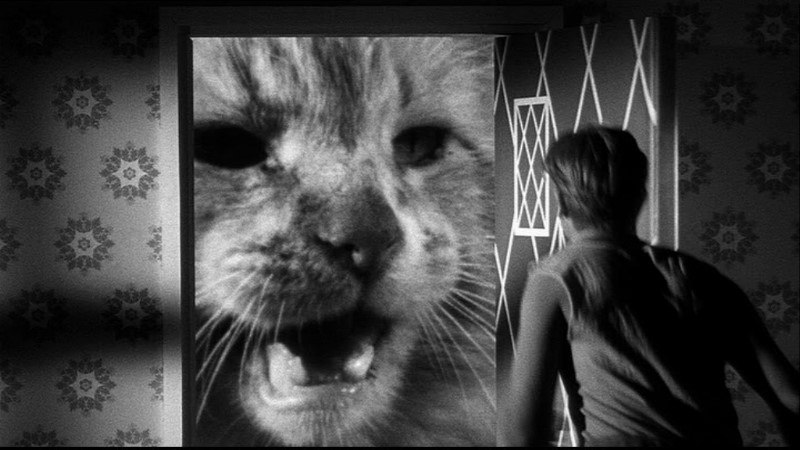

In 1957, Arnold made his last entirely great work, the only film he made that can seriously challenge Creature from the Black Lagoon as his masterpiece: The Incredible Shrinking Man. This streamlined adaptation of a Richard Matheson novel (scripted by Matheson himself) is one of the great inexplicable triumphs of all B-moviedom: a poster-ready premise and title with all the effects-driven spectacle promised therein (the shrinking man does battle with both a housecat and a tarantula – the same one that appeared in Tarantula, in fact), all of it folded into a rich and melancholy character study. The Incredible Shrinking Man isn't just an excuse for cheap thrills; it actively and earnestly tries to grapple with the psychological state of being the victim of one of those '50s science-gone-wrong movie plots, right up to a philosophically and religiously sweeping climactic monologue written, it is said, by Arnold himself. I can't name another a genre movie from the era that cares this much about the human cost inherent in the genre but usually ignored. I absolutely can't name one that's this good, both at providing that human foundation, and also at being sufficiently thrilling and confidently executed that it can stand proud as popcorn entertainment for those viewers who don't care much about thinking during their shrinking man movies.

Shrinking Man, along with Creature from the Black Lagoon, makes for a double feature that's all you really need to argue for Arnold's dominance of his field: these are two of the decade's most exceptional pieces of cinema even without the benefit of comparing them to all the dubious sci-fi of the period. If you haven't seen either of them, or any of Arnold's other works, there's no better time than right now: his uniquely intimate and tightly-crafted films are as impressive, and as fun, as midcentury cinema gets.