by Chris Feil

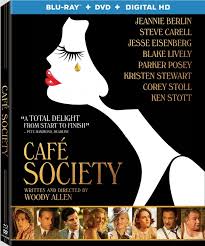

While never reaching the heights of his other showbiz-adjacent comedies, Woody Allen's Cafe Society has charm and gloss to spare. Allen is marking the same thematic territory and era fascinations as he has frequently visited in the past, here with more hidden snideness than much of his recent works. Under its sparkling surface, Society is a subtly mean-spirited film.

While never reaching the heights of his other showbiz-adjacent comedies, Woody Allen's Cafe Society has charm and gloss to spare. Allen is marking the same thematic territory and era fascinations as he has frequently visited in the past, here with more hidden snideness than much of his recent works. Under its sparkling surface, Society is a subtly mean-spirited film.

Much of that tone comes from Jesse Eisenberg's central performance as Bobby Dorfman, a transplant to 1930s Hollywood under the not so watchful eye of his talent agent uncle (Steve Carell). Bobby is quick to chase girls, ultimately arriving to (or creepily wearing down) secretary Vonnie (Kristen Stewart), who also is secretly having an affair with his uncle. Vonnie becomes Bobby's girl on an eternal pedestal, always more an idea of a person than the woman before him...

Eisenberg is biting when the script calls him to be naive - lacking that unintentional cruelty makes Bobby more soullessly cruel than intended. A scene with Anna Camp's prostitute loses all of the humor for this nastiness, but Bobby's romantic entanglements become quite implausible given the actor's irascibility. Much of the male cast is miscast and uneven, from a flat Carell to an overarched Corey Stoll as Bobby's gangster brother.

The film's real strength lies in its female ensemble giving inner life to stock characters, even if each is underused to some extent. Jeannie Berlin as Bobby's mother is as divine and hilarious as ever, inching her closer to the showcase she deserves. Stewart is as slippery as ever, finding seismic shifts for her character even as the script is disinterested with her. Sari Lennick turns the film's most tangential subplot into its most entertaining with harsh hilarity.

But the biggest surprise of the film is Blake Lively in a few short scenes in the film's back half. Even at its best the film is mannered, but Lively is light on her feet and offhandedly funny in a way that refreshes and ignites the film just as you think it's winding down. The actress is unexpectedly unruffled by the challenges of Allenese, very much her own persona without sacrificing Allen's standard, specific patter.

Cafe Society is also another Allen rumination on nostalgia, but never comes up with a consistent point of view. Bobby represents nostalgia being a certain state of mind and all of its inherent toxicity, with Allen never quite condemning or allowing his misguidedness (or even accepting ambiguity). The film also bathes in its own nostalgia, from Vittorio Storaro's lustrous cinematography and Suzy Benzinger's witty period costuming. The luxuriousness is seen through such rose tinted glasses that while it is quite entertaining, suggests that Allen may not be listening to his own themes. The film floats but never lands.

With a ceiling to its own charms, Cafe Society alternates between delight and frustration, specificity and vagueness. It's certainly not Woody Allen's most successful comedy, but more appetizing than most of his recent deliveries.

Grade: C+