"The Furniture" is our weekly series on Production Design. Here's Daniel Walber...

"The Furniture" is our weekly series on Production Design. Here's Daniel Walber...

This probably goes without saying, but movie musicals tend not to take place in the real world. Gene Kelly doesn’t just serenade French children in An American in Paris, he leads the cast through a dream ballet of wild abstraction. The oddness of public singing is often just the door to an even more fantastical world. Even those about actual musicians, who need no special excuse to croon, often break free from realism.

In this context, Dreamgirls is a bit of an odd duck. Director Bill Condon tries to split the difference. Some of the songs are entirely within the context of a real performance, while others incorporate non-musician characters and non-realistic settings. The back and forth can be a bit confounding...

Yet there’s a thematic arc that depends on this odd variety. The Oscar-nominated work of production designer John Myhre (Chicago), art director Tomas Voth (Nine) and set decorator Nancy Haigh (Hail, Caesar!) is crucial to telling this story.

Dreamgirls begins in the wings of a Detroit theater. The stage is bare, the curtain simple. The plot is set in motion by a backstage deal, lit more like a neo-Noir than a buoyant musical.

The bargain sends the Dreamettes on the road with Jimmy Early (Eddie Murphy). Each stage set of the tour is a variation on a single theme. A lit-up sign with Jimmy’s thunderbolt logo hangs in front of a monochrome curtain. It’s inexpensive but flashy, a modest mark of success in a marginalized area of the American music industry.

Eventually, a concerted payola campaign buys Jimmy and the Dreamettes tambourine-wielding dancers and an elevator platform. They’re on the rise.

Along the way, “Cadillac Car” gets stolen and ruined by white TV, performed on an inert car in front of fake palm trees and a painted horizon. It’s significant that we actually see the full set, rather than only the black & white broadcast that the Dreamettes watch. This is the film’s first glimpse of mainstream culture as a flattening, soulless experience.

Anyway, the Dreamettes move on from Jimmy and become the Dreams. The apex of the first act comes with their debut, with Deena (Beyoncé) replacing Effie (Jennifer Hudson) in lead. Lights flicker everywhere, abstracting the nightclub. This is the moment of crossover. The wings, where the action began, have disappeared. The Dreams have been shot upward, out of the real world and into a sort of fame-space.

The tension between the Dreams, Curtis and C.C. (Keith Robinson) only escalates. When it finally comes to a head, the backstage drama takes on the same celestial air as the concert. Everything is dark but the stage, which is adorned with white curtains, a white piano and skinny lights. It’s almost heaven.

Then it cracks.

Suddenly there are mirrors everywhere, fanning out the reflections of everyone who passes by. Effie’s voice shatters the original Dreams, like the most fragile glass.

From here on out, the production design is as split as the narrative. The jazz club where Effie makes her comeback is polar opposite of a Las Vegas nightclub. There’s a real city outside those windows. Real fog blocks the view. There may be transcendence here, but it’s all in Effie’s voice.

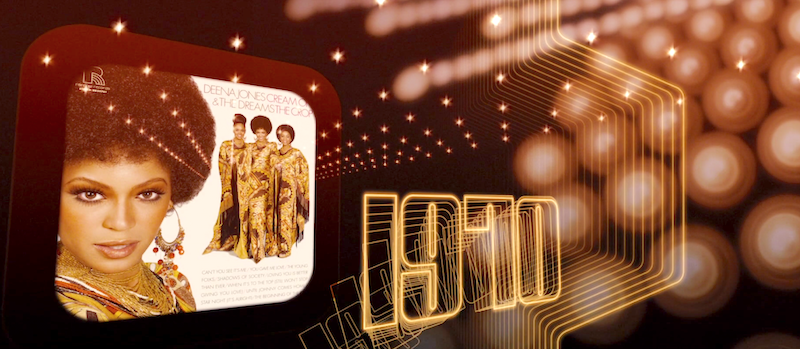

Deena, meanwhile, lives entirely in fame-space. She barely performs. Instead, there’s an endless parade of album-covers, chronicling the success of the post-Effie Dreams without much evidence of music.

There’s also plenty of promotional material for the Cleopatra biopic that Curtis has planned for Deena. Its image precedes its realization, dooming it from the start.

She lives in the shadow of her own face. She is fame itself, the abstracted idea of celebrity, a powerful image with the depth of wallpaper.

Her performance of a disco-fied “One Night Only” is, therefore, supposed to be a bit strange. It’s as false as the whitewashed “Cadillac Car.” On the one hand, this style makes Dreamgirls uneven. Scenes feel ripped from different films. The production design echoes this disjointed mood, contrasting Effie’s strength to Deena’s image. It’s a messy approach, to be sure, but you can’t deny its drama.