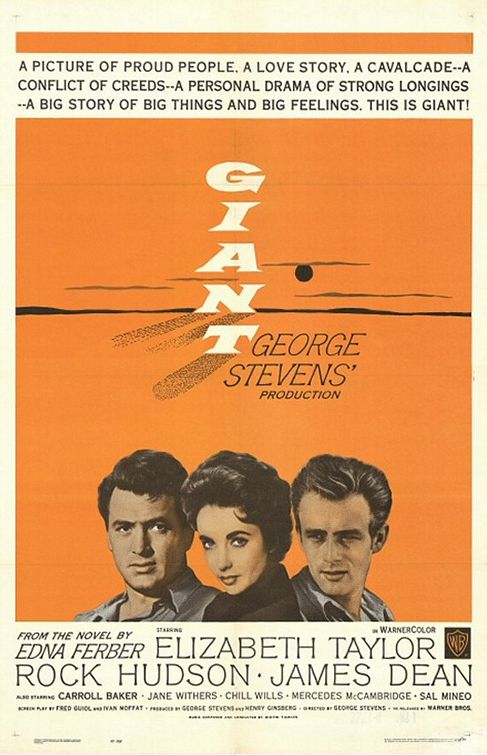

Our second chapter of the Centennial Mercedes McCambridge celebration is also the second time Oscar celebrated her. She received her second and final nomination in Best Supporting Actress for Giant, a massive epic about social discrimination affecting a wealthy Texas ranching family. Here she's playing opposite massive stars Elizabeth Taylor, Rock Hudson, and James Dean (his final performance), but McCambridge still lingers over the film after her staunch matriarch Luz Benedict departs. She has perhaps only twenty minutes of screentime at the start of the film's sprawling length, it's a brief performance that the actress makes both broad and oddly complete.

Our second chapter of the Centennial Mercedes McCambridge celebration is also the second time Oscar celebrated her. She received her second and final nomination in Best Supporting Actress for Giant, a massive epic about social discrimination affecting a wealthy Texas ranching family. Here she's playing opposite massive stars Elizabeth Taylor, Rock Hudson, and James Dean (his final performance), but McCambridge still lingers over the film after her staunch matriarch Luz Benedict departs. She has perhaps only twenty minutes of screentime at the start of the film's sprawling length, it's a brief performance that the actress makes both broad and oddly complete.

You might call her performance wooden or inexpressive if you've never experienced this kind of woman in real life. The stoic inexpressiveness and static undercurrent of rage is eerily familiar if you're accustomed to this brand of southern woman, one who has been toughened up by a man's world and educated to hate. McCambridge respects the deliberate unknowability with which Luz wants to greet the world - this is a woman who has thrived on not letting anyone in to subvert her authority. She wears Luz's hatred (and self hatred?) like an impenetrable shield of armor, as her eyes offer the only suggestion of more brewing underneath the facade. More...

McCambridge had spoken of the toll taken on her by the hardened women she had played, and it's all right there in her weathered face. McCambridge's radio work might be the root of her being foremost praised for her vocal specificity, but her work in Giant is physically well-observed and smartly muted.

Luz is purposefully presented plainly against the star wattage glamour of Taylor's Leslie, but you sense the actress also modulating physically against the movie star. McCambridge thick dialect is flat against Taylor's vivid delivery, and McCambridge barely moves compared to Taylor's grace. Her behavior establishes the threat Luz sees on the arrival of her new sister-in-law and her ideas of acceptance, while remaining true to a woman not prone to physical flourish. Luz claims to hold sway with her Mexican farmhands with brute verbal control, but the actress does so with stillness during her brief screentime. There are no fireworks coming from their tension, for outright argument would mean that somehow Luz has already lost a piece of control.

That attempt at control is ultimately Luz's downfall as she forcefully tries to prove her dominance over the Mexican ranch hands she despises by riding the wildest horse. She's thrown from the horse impersonally off-screen, simultaneously losing both her battle for dominance and her individuality. In her death, director George Stevens shows the power of our hatred to define us over any other characteristic once we're gone. But it's McCambridge doing the character building to make sure the thesis sings.

Ultimately, we're left with the internally unknowable within McCambridge's portrayal of Luz to tantalize us most. She enters the film unceremoniously, and exits just as visually insignificant, her cruelty robbing her of her own humanity. It's the frustrating experience of a compelling actress drawing the audience in just enough, but also working in tandem with the film to support the narrative by keeping us at arm's length. It's also a reminder and warning of what hatred can do to a person and their legacy - render them inert in life and insignificant in death.

Previously: an Oscar win for All the King's Men (1949)