Glenn here. Each Tuesday we bring you reviews and features on documentaries from theatres, festivals, and on demand. In celebration of not just the Cannes Film Festival, which is underway right now, but also the release of my book Cannes Film Festival: 70 Years out now through Wilkinson Publishing, we're looking at only the second documentary to win the Palme d'Or. The book is a glossy trip through history, looking at the festival's beginnings, the films, the moviestars, the fashions and the controversies. You better believe I convinced my editors on a double-page Nicole Kidman spread!

Glenn here. Each Tuesday we bring you reviews and features on documentaries from theatres, festivals, and on demand. In celebration of not just the Cannes Film Festival, which is underway right now, but also the release of my book Cannes Film Festival: 70 Years out now through Wilkinson Publishing, we're looking at only the second documentary to win the Palme d'Or. The book is a glossy trip through history, looking at the festival's beginnings, the films, the moviestars, the fashions and the controversies. You better believe I convinced my editors on a double-page Nicole Kidman spread!

Just earlier this year I said of Michael Moore’s most recent film, Where to Invade Next?, that it was “utterly disgraceful” and that it was bound to “truly be one of the year’s worst movies.” That film was on my mind as I sat down to rewatch the director’s 2004 Palme d’Or winning documentary, Fahrenheit 9/11. Would the impact of that initial viewing of Fahrenheit 9/11 remain all these years later now that my eyes and mind are much wider? It’s a little bit of yes and a little bit of no. ...more after the jump.

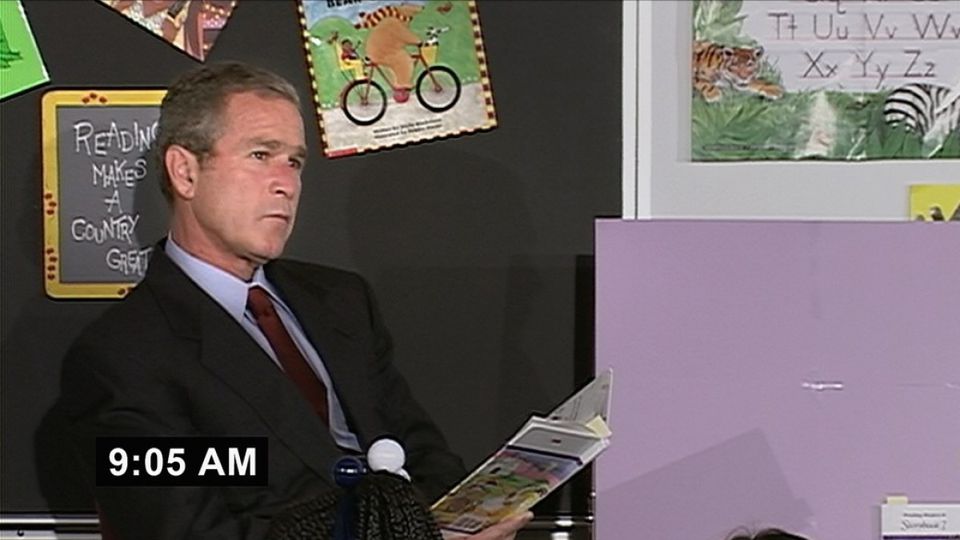

I had certainly forgotten that only half of the film’s two-hour runtime was devoted to making George W. Bush look like a bumbling fool. As comical as it is to watch Bush’s many gaffes, audiences could get that from the late night shows and news entertainment programs. I did find, however, many of the ideas of the second half regarding soldiers and their families’ gradual realization to the true nature of the war to be more impressive. Albeit handled in frustratingly simplistic ways that undermined his intent.

In many ways, the film is the most quintessential Michael Moore film, revelling as it does as much in the idiocy of government officials as it does the suffering of the common man with whom he clearly identifies (Moore even revisits him hometown of Flint for no other reason than he can). It is manipulative, most definitely, as all of his films are, and full of the playful yet awkward and irksome muckraking that he is known for. But at least it is compiled with verve and spirit thanks predominantly to the team of editors: Kurt Engfehr, Woody Richman and Chris Sewart. I was also pleased to find the central thrust of this film was something still worth getting fired up about and still worth watching as a time capsule of an era of (for many) national despair in the face of unfathomable tragedy. And like many films documenting this era of America politics, it remains alarmingly relevant for today.

Upon being awarded the Palme d’Or, jury president Quentin Tarantino is reported to have said, “I just want you to know it was not because of the politics that you won this award. You won because we thought it was the best film that we saw.” Whether you believe that or not – and, let's face it, who does? – I think its win is far from a blight. Glancing at the films that premiered that year at Cannes and it is a line-up filled predominantly with directors who would have made for equally curious winners in hindsight. Films by Olivier Assayas (Clean), Wong Kar-Wai (2046), Apichatpong Weerasethakul (Tropical Malady), Agnes Jaoui (Image of Me), Emir Kusturica (Life is a Miracle), Hirokazu Koreeda (Nobody Knows) and Walter Salles (The Motorcycle Diaries) have likely all aged better than Moore's, and yet lack the exciting narrative to propel their films to career-defining status for their filmmakers. It would be like Moore winning for Sicko. I'd posit that the only film among the line-up to have continued to grow in stature to almost unanimous acclaim as a masterpiece well beyond its Cannes birth is Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy, which would have no doubt been a more liked winner in retrospect (despite my own misgivings towards it).

Upon being awarded the Palme d’Or, jury president Quentin Tarantino is reported to have said, “I just want you to know it was not because of the politics that you won this award. You won because we thought it was the best film that we saw.” Whether you believe that or not – and, let's face it, who does? – I think its win is far from a blight. Glancing at the films that premiered that year at Cannes and it is a line-up filled predominantly with directors who would have made for equally curious winners in hindsight. Films by Olivier Assayas (Clean), Wong Kar-Wai (2046), Apichatpong Weerasethakul (Tropical Malady), Agnes Jaoui (Image of Me), Emir Kusturica (Life is a Miracle), Hirokazu Koreeda (Nobody Knows) and Walter Salles (The Motorcycle Diaries) have likely all aged better than Moore's, and yet lack the exciting narrative to propel their films to career-defining status for their filmmakers. It would be like Moore winning for Sicko. I'd posit that the only film among the line-up to have continued to grow in stature to almost unanimous acclaim as a masterpiece well beyond its Cannes birth is Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy, which would have no doubt been a more liked winner in retrospect (despite my own misgivings towards it).

Whatever the case may be, Fahrenheit 9/11 remains one of Cannes’ most interesting selections. A radically bold choice that played to the festival’s obvious love for politics, American cinema as well as their need to emerge out of the hushed shadow of the previous year’s winner, Elephant. I suspect it's win continues to be felt in Cannes, and I would be willing to bet that the divisiveness of its Palme d’Or is partly to blame for no documentaries having been in the Cannes line-up since with only the exception of Waltz with Bashir. A flawed method to curb the potential for jury members in a highly politicized world from giving the most prestigious honour in world cinema to films that merely align with their social views.

The festival did introduce the Oeil d’Or (or the Golden Eye) last year, a prize for documentaries that covers all strands of the festival. Comfort of mind for documentary filmmakers, I guess, knowing Ken Loach yet again didn’t lose his competition slot to works of cinematic art that have the poor misfortune of being non-fiction. Films competing for the prize this year include Jim Jarmusch’s Iggy Pop doc Gimme Danger, Bernard-Henri Levy’s Peshmerga, Thanos Anastopoulos and David Del Degan The Last Resort, Laura Poitras' Risk, and – most excitedly for myself – Rithy Panh’s Exile. I look forward to seeing whichever one wins, but maybe in the future the Cannes selectors could give them the competition highlight they deserve.

Cannes Film Festival: 70 Years is available through online retailers, through both Barnes & Noble and Books a Million in the USA, and in stores across Australia.

Just earlier this year I said of Michael Moore’s most recent film, Where to Invade Next?, that it was “utterly disgraceful” and that it was bound to “truly be one of the year’s best movies.” That film was on my mind as I sat down to rewatch the director’s 2004 Palme d’Or winning documentary, Fahrenheit 9/11. Would the impact of that initial viewing of Fahrenheit 9/11 remain all these years later now that my eyes and mind are much wider? It’s a little bit of yes and a little bit of no.

I had certainly forgotten that only half of the film’s two-hour runtime was devoted to making George W. Bush look like a fool. As comical as it is to watch Bush’s many gaffes, I found many of the ideas of the second half regarding soldiers and their families’ gradual realization to the true nature of the war to be more impressive. Albeit handled in frustratingly simplistic ways that undermined his intent.

In many ways, the film is the most quintessential Michael Moore film, revelling as it does as much in not just the idiocy of government officials, but in the suffering of the common man. It is manipulative, most definitely, and full of the playful yet awkward and irksome muckraking that he is known for. But at least it is compiled with verve and spirit thanks predomantly to the team of editors: Kurt Engfehr, Woody Richman and Chris Sewart. I was also pleased to find the central thrust of this film was something still worth getting fired up about and still worth watching as a time capsule of an era of (for many) national despair in the face of unfathomably tragedy. Like many films documenting this era of America politics, it remains alarmingly relevant for today.

Upon being awarded the Palme d’Or, jury president Quentin Tarantino is reported to have said, “I just want you to know it was not because of the politics that you won this award. You won because we thought it was the best film that we saw.” Whether you believe that or not – and I’m not sure I do – glancing at the films that premiered that year at Cannes and it is a line-up filled predominantly with directors who would have made for equally curious winners in hindsight. Filmmakers like Olivier Assayas (Clean), the Coen brothers (The Ladykillers), Wong Kar-Wai (2046), Apichatapong Weerasethakul (Tropical Malady), Agnes Jaoui (Image of Me), Emir Kusturica (Life is a Miracle), Hirokazu Koreeda (Nobody Knows) and Walter Salles (The Motorcycle Diaries) among those whose narratives weren’t in sync with the films on offer. The only film among the line-up to have continued to grow in stature since its release to near unanimous acclaim as a masterpiece is Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy, which would have no doubt been a more liked winner in retrospect (despite my own misgivings towards it).

Whatever the case may be, Fahrenheit 9/11 remains one of Cannes’ most interesting selections. A radically bold choice that played to the festival’s obvious love for American cinema as well as their need to emerge out of the hushed shadow of the previous year’s winner, Elephant. Still, it’s win – I suspect – continues to be felt and I would be willing to bet that the divisiveness of its Palme d’Or is partly to blame for no documentaries having been in the Cannes line-up since with only the exception of Waltz with Bashir. A method to curb the potential for jury members in a highly politicized world from giving the most prestigious honour in world cinema to films that merely align with their social views.

The festival did introduce the Oeil d’Or (or the Golden Eye) last year, a prize for documentaries that covers all strands of the festival. Comfort of mind for documentary filmmakers, I guess, knowing Ken Loach yet again didn’t lose his competition slot to works of cinematic art that have the poor misfortune of being non-fiction. Films competing for the prize this year include Jim Jarmusch’s Iggy Pop doc Gimme Danger, Bernard-Henri Levy’s Peshmerga, Thanos Anastopoulos and David Del Degan The Last Resort, and – most excitedly for myself – Rithy Panh’s Exile.