For Pride month, we're celebrating our favorite queer moments in cinema. Here's guest contributor Steven Fenton...

For Pride month, we're celebrating our favorite queer moments in cinema. Here's guest contributor Steven Fenton...

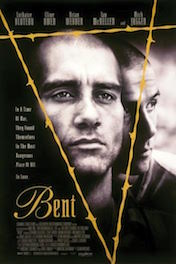

Bent is the story of two men who fall in love while imprisoned in Dachau concentration camp during WWII. When the original play premiered in 1979 it made waves for its powerful depiction of Nazi persecution of homosexuals. By the time the film was released eighteen years later, the AIDS epidemic had ravaged the global gay community, giving further significance to the story’s exploration of survival and freedom.

In the camp, Max (Clive Owen) and Horst (Lothaire Bluteau) are assigned the sisyphean task of hauling stones from one rubble pile to another. On a miserably hot day, Horst attempts to distract Max from the maddening heat and labor. [More...]

He reveals he’s been sneaking glances at Max tells him how sexy he is - Max confesses the same. The tone shifts when Horst asks Max whether he misses sex.

Max: Yes

Horst: Me too. We don’t have to. We’re here together. We don’t have to miss it.

Max: We can’t look at each other. We can’t touch.

Horst has something else in mind. He whispers all the things he’d like to do to Max. He asks if Max can feel his touch, his kiss, his tongue. They grow more aroused as the guards look on unsuspectingly; the tension mounting. They sink into a haze of lust and desire; sharing their deepest sexual impulses, breathing heavily, until they simultaneously climax.

Horst: We did it. How about that - fucking guards, fucking camp, we did it.

Max: Don’t shout.

Horst: O.K. But I’m shouting inside. We did it. They’re not going to kill us. We made love. We were real. We were human. We made love. They’re not going to kill us.

This scene stays with you. It’s sexy without being obscene, and it’s the only time they smile throughout the film. The joy they find in their rebellious act is infectious. Horst’s final line is especially poignant; asserting his absolute determination to stay true to himself, even in the most impossible circumstances.

Nineteen years after the film’s release, this scene is as relevant to the queer experience today as it was in 1997. It’s a beautiful and optimistic moment that argues the path to survival is taking charge of your destiny and true freedom is finding the courage to be yourself. It’s a potent message that still resonates with a community that faces a daily fight for dignity, respect, and freedom.