1984 is our "Year of the Month" for August. So we'll be celebrating its films randomly throughout the month. Here's Daniel Walber...

Simon Callow as PapagenoAmadeus is not a biopic, it’s a myth. Milos Forman’s adaptation of Peter Shaffer’s play is an utterly absurd portrayal of a long ago, unknown relationship. Antonio Salieri may not have had any negative feelings toward Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, but that hardly matters. The legend, a story of deep faith that twists into jealousy, is a whole lot more interesting than the truth.

Simon Callow as PapagenoAmadeus is not a biopic, it’s a myth. Milos Forman’s adaptation of Peter Shaffer’s play is an utterly absurd portrayal of a long ago, unknown relationship. Antonio Salieri may not have had any negative feelings toward Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, but that hardly matters. The legend, a story of deep faith that twists into jealousy, is a whole lot more interesting than the truth.

The film’s production design mimics the delicious falseness of its narrative. The Vienna of Emperor Joseph II is opulent, to be sure, but it is a strange opulence. Rather than focus on the grandeur of the palaces, Forman keeps much of the drama in drawing rooms. Production designer Patrizia von Brandenstein and art director Karel Cerny keep away from too much gold and silver, instead creating bizarre tableaux of a miniature society.

Even more striking are the recreations of the opera theater. For these, Forman called on Joseph Svoboda, the founder of Prague’s Laterna Magika and an internationally renowned opera director. He produced scenes from four of Mozart’s operas for the film, as well as one by Salieri.

They are all both extravagant and shabby, in line with both the presumed wealth of Emperor Joseph II’s court and the theatrical limitations of the 18th century...

The first is the debut of Mozart’s The Abduction from the Seraglio, a “rescue opera” set in Turkey. Svoboda’s sets are flashy, flimsy examples of Viennese orientalism.

The same sort of stagecraft characterizes the next operatic production as well, for The Marriage of Figaro. Here the point is to underline the absurdity of the Emperor’s ban on ballet, a moment of bizarre comedy.

It’s a pocket-sized pastoral, coaxing along Mozart’s heartfelt but unpretentious music. That’s what drives Salieri so nuts about him, the fact that he composes such melodies and harmonies without either pomposity or exertion.

Salieri, meanwhile, works in a grand tradition of over-the-top opera seria. His protagonists are all stiff mythological heroes, floating statues that glide above the audience. Svoboda’s sole Salieri production fits the bill, an enormous black staircase on which a cast of thousands belts out the final, biblical chorus.

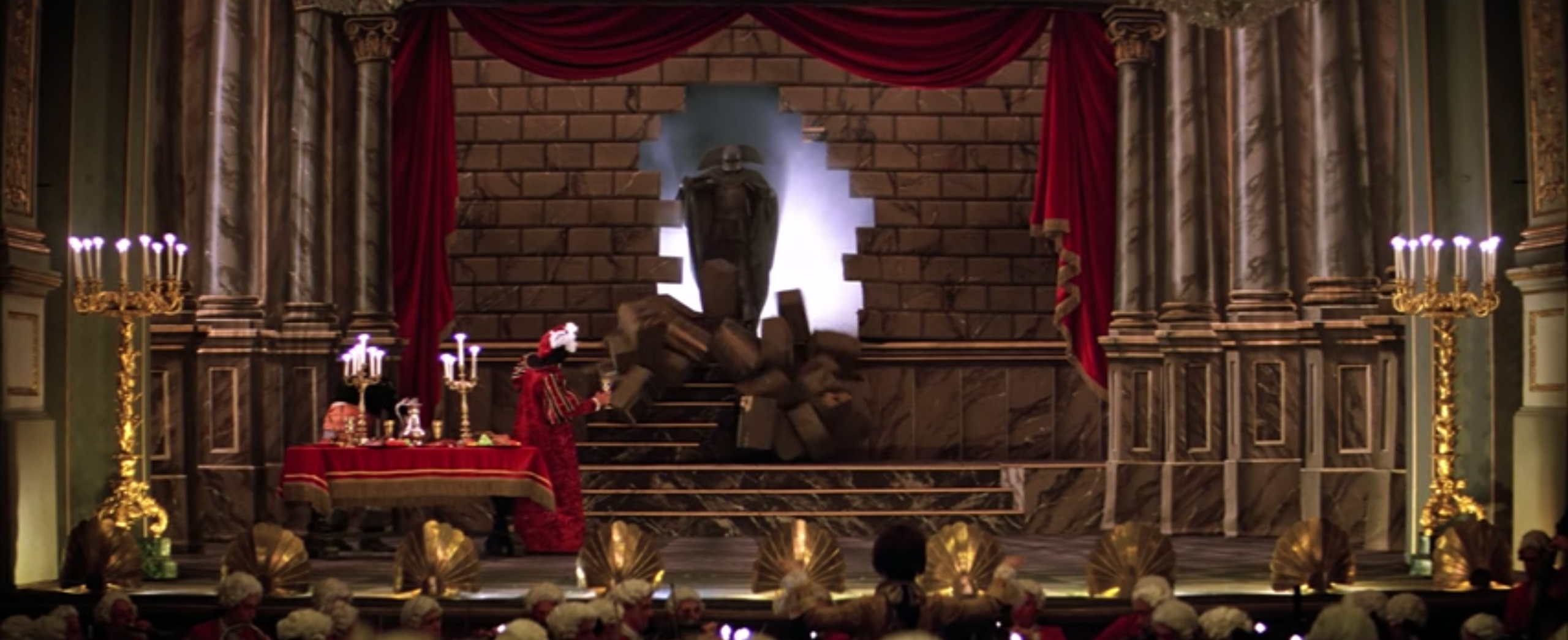

By Don Giovanni, however, Mozart’s mood has swung lower than Salieri’s. Stunned by the death of his father, the young composer puts his guilt and anxiety on stage in the form of the terrifying Commendatore.

At first, Svoboda’s set seems a bit silly. The singing statue bursts easily through the transparently flimsy wall at the back of the stage. Yet it’s not his job to supply the mood, but rather to contain the power that springs forth from Mozart’s music.

By the time the final wall collapses, the point has been made. The collapse of the set isn’t viscerally impressive in its own right, but is the ideal companion to the towering music and the feverish look on the composer’s face.

After all, this is only a myth. Mozart and Salieri are ideas, not men. Svoboda’s paper opulence, despite the fact that it inhabits classical music’s most extravagant genre, is what keeps the film on course toward a wry and symbolic conclusion.

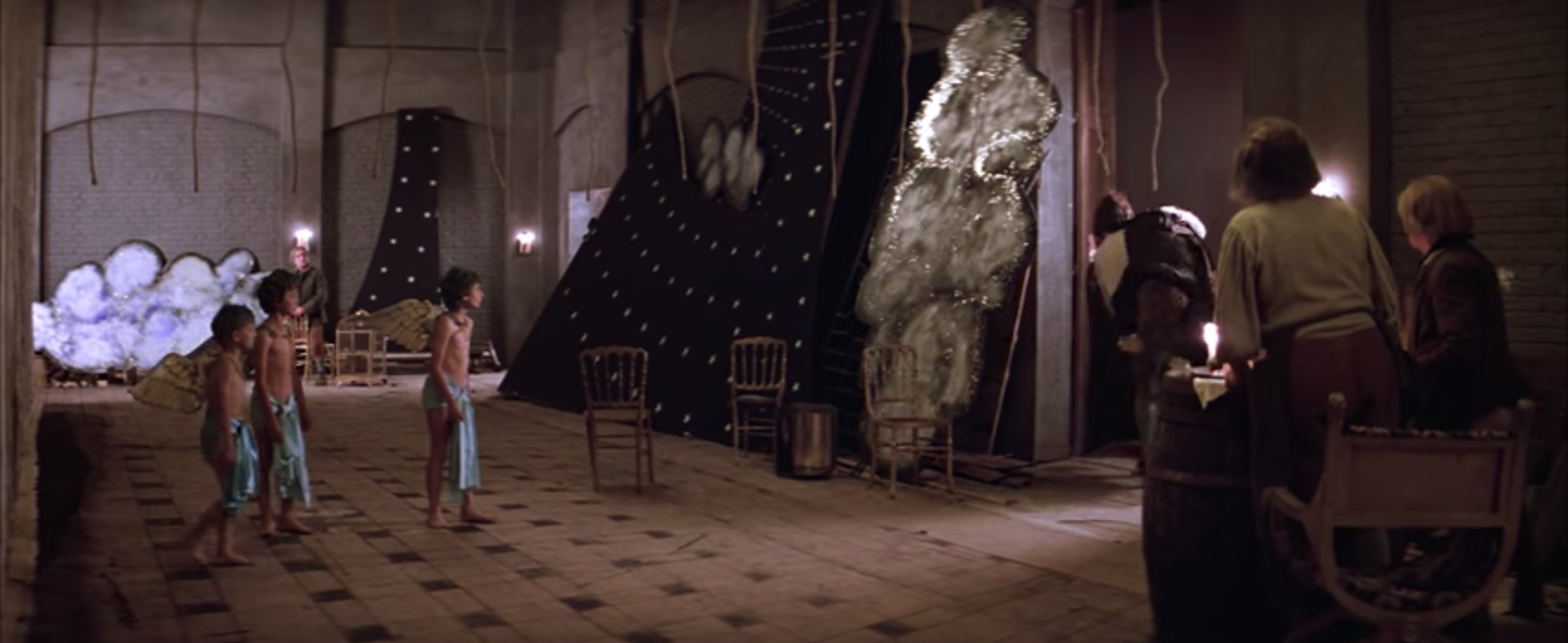

For a final example, then, let us turn to the most fantastical of Mozart’s operas. He wrote The Magic Flute for the vaudeville theater of Emanuel Schikaneder, rather than the court of the Emperor. Svoboda’s flashiest set is the one from which the Queen of the Night sings her famous aria. A blue, starry sky radiates out from her cloud, entrancing the audience.

In the next scene, Mozart collapses and is rushed backstage. The pieces of this transcendent set lean against the wall. The magic spell has been quietly broken. We see Svoboda’s work, and that of opera more broadly, for what it is: a fragile fantasy elevated to the status of myth by the power of music. The film itself is the same, a tale as flimsy as painted cardboard transformed into something truly magnificent.