By Daniel Walber.

What makes a film theatrical? It’s a word that gets bandied about a lot. Often it just means that the script is like that of a play, with a limited number of locations and lots of dialogue. Or it can be used to describe a style of acting, playing to the rafters rather than the more intimate audience of the camera lens. Rarely, however, do we use the word “theatrical” to describe elements of direction, cinematography and editing.

What makes a film theatrical? It’s a word that gets bandied about a lot. Often it just means that the script is like that of a play, with a limited number of locations and lots of dialogue. Or it can be used to describe a style of acting, playing to the rafters rather than the more intimate audience of the camera lens. Rarely, however, do we use the word “theatrical” to describe elements of direction, cinematography and editing.

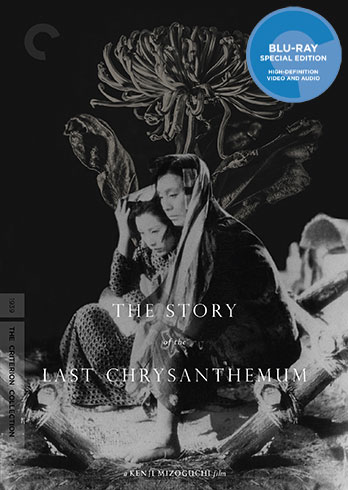

Yet this underserved implication of the term is the key to understanding The Story of The Last Chrysanthemum, an early triumph of iconic Japanese director Kenji Mizoguchi that has just been released by the Criterion Collection. This epic family drama was a proving ground of sorts for the filmmaker’s signature use of long takes, which would elevate such later masterpieces as Ugetsu and The Life of Oharu. But first he took a much narrower approach, crafting the style of The Story of The Last Chrysanthemum from the conventions of kabuki theater.

Kabuki, like cinema, specializes in artistic trickery. Yet live theater doesn’t have the benefit of editing, the foundation of cinematic sleight of hand. Instead, kabuki actors use a wide variety of theatrical tricks to astound the audience. The Story of the Chrysanthemums begins with some of these feats, a series of quick changes punctuated by uproarious applause. It is all done right in the open, magic performed at the center of the wide kabuki stage.

He also avoids close-ups. This prioritizes the relationships between actors over the minute details of their personal responses, another element that mimics the experience of the stage. There is often a great deal to look at, allowing the sort of viewer freedom that cinema often tries to restrict.

Take, for example, one crucial shot. The scene is of the first meeting between Otoku and Kikunosuke, presented in an uninterrupted 5-minute take. The two characters walk the length of the street together, as we observe from a distance. They stroll past wind chimes, which continue to punctuate the scene like kabuki’s omnipresent percussion. This long moment is both theatrical and understated, a remarkable combination given the way we usually use the word “theatrical.”

It is this innovation that makes The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum one of the most stylistically significant films of the 1930s, one that always rewards a fresh glance.