"The Furniture" our weekly series on Production Design. Here's Daniel Walber

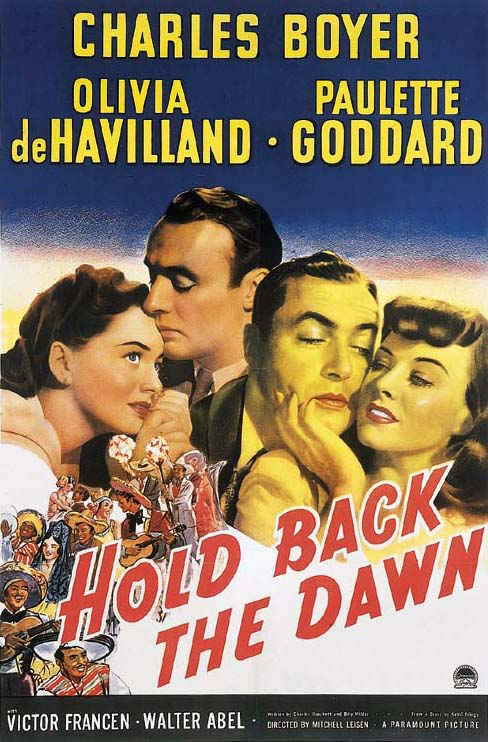

Today marks the 75th anniversary of the release of Hold Back the Dawn, the film for which Olivia de Havilland received her first Best Actress nomination. Now, I know what you’re thinking. Didn’t we have a whole month of de Havilland back in June, in the lead-up to her 100th birthday? Yes, we did. But I am here to inform you that celebrating this two-time Oscar-winner isn’t an occasional thing. It's an essential part of life.

Today marks the 75th anniversary of the release of Hold Back the Dawn, the film for which Olivia de Havilland received her first Best Actress nomination. Now, I know what you’re thinking. Didn’t we have a whole month of de Havilland back in June, in the lead-up to her 100th birthday? Yes, we did. But I am here to inform you that celebrating this two-time Oscar-winner isn’t an occasional thing. It's an essential part of life.

Besides, the film is great. It’s a smart, cynical melodrama about a Romanian playboy named Georges Iscovescu (Charles Boyer), biding his time in a small Mexican town while he waits to be granted entry into the United States. It’ll be years, thanks to the National Origins Formula. Charles Brackett and Billy Wilder’s script was adapted from a story by Ketti Frings, but also took inspiration from Wilder’s own experiences as a refugee stranded by the quota system.

Fed up, Georges looks for other ways to get across. On the 4th of July he meets Emmy Brown (de Havilland), a thoroughly wholesome schoolteacher. She’s taken her students on a cross-border field trip...

Never mind the fact that it’s the middle of summer, or that Independence Day is a weird date to pick for a trip out of the country. Her car breaks down, Georges puts the moves on her, and the whole class ends up spending a night at the Hotel Esperanza. Next thing you know it, they’re married.

In a sense, she’s also been kept here by the energy of the place. People don’t often leave, especially not the international clientele of the Esperanza. Director Mitchell Leisen keeps things claustrophobic, never showing the full scope of the town. We mostly get are shots like these, looking across the central square from one building to another.

Much of this was shot on the Paramount Ranch, where the studio regularly recreated the Old West. Yet unlike other films made there, Hold Back the Dawn doesn’t show off its sets. Instead, cinematographer Leo Tover and art directors Hans Dreier and Robert Usher conspire to underscore the cramped atmosphere. We see the same buildings over and over. The “Climax Bar,” an unassuming watering hole, is used like punctuation.

Here it is again, framing Georges. The humdrum life of the Esperanza’s exiles is one of endless repetition.

The only anomaly is the border checkpoint itself. It stands as a cold and imposing promise of a different world, of which we know nothing. The film rarely approaches the fence, choosing instead to lurk at a distance. It’s maddening. The gates could lead to the afterlife, for all we know, or to Toontown, or off the edge of the planet.

It’s so close, and yet so abstract. The entire USA is represented by a cluster of palm trees and a wall of forbidding wire. As Georges narrates, the fence might as well be “a thousand feet high.” Yet the actual distance is only a few feet. That’s small enough for Esperanza guest Berta Kurz to sneak through unnoticed, giving her just enough time for childbirth on American soil. Of course, we are only granted the sound of a baby's cry. We never get to see inside.

It’s no surprise, then, that the film’s two extended trips away from town feel liberating in comparison. First is a sudden honeymoon into the Mexican countryside, a lovely diversion that sets Georges down the road to real love for Emmy.

Later, the news of Emmy’s car accident confirms these feelings. Georges hops into a car and drives right through the border, desperate to make it to the wounded Emmy’s bedside. The border officers chase after him, but he miraculously manages to get away.

After an entire film of enclosed spaces, restrictive fences and humbling architecture, the plaza of Los Angeles County General Hospital looks like the steps of heaven itself. Obviously the building wasn’t built especially for Hold Back the Dawn, but it wouldn’t be nearly as much of a revelation if it didn’t follow such perfect sets. It is, in its own indirect way, a testament to the production designers’ triumph.