by Kyle Stevens

Professor Indiana JonesAfter teaching for years as a graduate student, then as a postdoc, and then as a Visiting Assistant Professor, I’ve finally started a proper position as Assistant Professor of Film Studies. As semesters begin all over the country, I turned to thinking about my favorite on-screen professors. High school movies tend to serve as microcosms of society; they’re all emotional peaks and valleys, in-groups and out-groups, and the goal is to get out. In college movies, from Animal House and Old School to Legally Blonde and The House Bunny, the goal is to stay on the rip-roaring ride of university life.

Professor Indiana JonesAfter teaching for years as a graduate student, then as a postdoc, and then as a Visiting Assistant Professor, I’ve finally started a proper position as Assistant Professor of Film Studies. As semesters begin all over the country, I turned to thinking about my favorite on-screen professors. High school movies tend to serve as microcosms of society; they’re all emotional peaks and valleys, in-groups and out-groups, and the goal is to get out. In college movies, from Animal House and Old School to Legally Blonde and The House Bunny, the goal is to stay on the rip-roaring ride of university life.

Not surprisingly, college teachers don’t feature heavily in these movies. And in other genres where professors pop up, they’re not exactly realistic. Think Harrison Ford as Indiana Jones, Eddie Murphy in The Nutty Professor, Natalie Portman in Thor, Hugh Grant in The Rewrite, and so on. (Propriety dictates that I not comment on the realism of Bruce Humberstone’s 1952 Virginia Mayo vehicle She’s Working Her Way Through College.) Television doesn’t fare much better, as the patently absurd characters in How to Get Away with Murder or Transparent attest.

But here are my personal favorites. The Top Five Professors in Film..

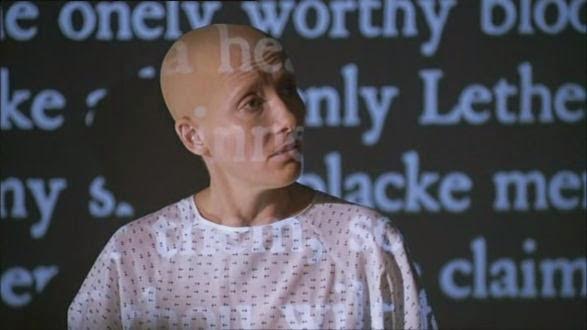

01 Emma Thompson in Wit (Mike Nichols, 2001)

Emma Thompson plays Vivian Bearing, an English professor diagnosed with “stage IV cancer.” She has thought about life and death her entire professional life, and now all that theory is being put into practice. It is a movie about the experience of being tested, and she passes. She keeps her wits, in an old-fashioned sense. Thompson—of course—nails how a lecture can feel both rote and urgent at the same time, and how 30 years of drinking six cups of coffee a day and institutional hierarchies lead to a hardness of the personality. Thompson subtly conveys Vivian’s distaste for academic bureaucracy while never diminishing her conviction in the importance of her subject: that understanding even one poem can involve confronting the grandest metaphysical questions as well as considering a single punctuation mark, and that these might be the same thing.

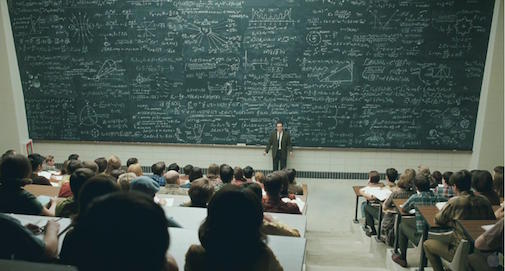

02 Colin Firth in A Single Man (Tom Ford, 2009)

This is a potentially scandalous choice to single out as realistic, I know. I don’t mean that professors are typically distracted by blue eyes like Nicholas Hoult’s in the lecture hall (though a fuzzy cream angora sweater will draw the eye). Rather, Ford and Firth get something right about the feeling of lecturing. They capture the arc of a class, the way it starts out bold, on topic, and then meanders a bit—and how time can completely get away from you! Firth nails the verbal gearshift between the “professional” tone of talking about literature and the more personal tone as he tries to explain to the students how their discussion is relevant to their lives. He sounds like a pedagogue who wants to share wisdom either way, but it’s clear which he cares more about. The movie lets the personal come through the performance of the perfectly groomed besuited professor. As for a student fancying Professor Falconer, what college student never crushed on a professor? I did, on my French Lit professor, and I can still vividly picture him writing on the blackboard in the jeans he so often wore.

03 Philip Hubbard in The Blot (Lois Weber, 1921)

Weber’s 1921 gem might be old, but its depiction of the genteel poverty of academics sure is timely. The story centers on the family of Andrew Griggs (Philip Hubbard), a caring and gifted professor unappreciated by the majority of his wealthy students. The family suffers a series of humiliations (including Mrs. Griggs’s moving attempts to steal food from the shoe-selling neighbors), and, eventually, the film offers up a happy ending after a student who woos Griggs’s daughter Amelia not only pays off their debts but writes to his father—the college’s wealthiest trustee—to demand the teachers be given a living wage. If this all sounds too didactic, it is a credit to Weber that she makes the drama feel so very human.

04 Michael Stuhlbarg in A Serious Man (Coen Brothers, 2009)

Poor Dr. Larry Gopnik is subjected to an avowedly Old Testament series of tests. And the dynamic tension holding the movie together is Michael Stuhlbarg’s electrically earnest resolve to find meaning in it all. But what, he eventually has to ask, does meaning mean? That’s a scary question for a physics professor accustomed to knowing the causes and principles on which the universe run. He’s trained to discover new connections, and yet, what if he can’t? To paraphrase one of my favorite professors, science seeks to discover and the humanities explain what’s already there. Gopnik’s predicament is an argument for the value of the film itself.

05 Julia Roberts in Mona Lisa Smile (Mike Newell, 2003)

Okay, so maybe I just have a soft spot for any movie that proves Julia Roberts can’t be outshined, even by an army that includes several of the most talented actresses of the younger generation. Mona Lisa Smile is set in the early 1950s—surely the most transitional moment in American higher education as schools went co-ed and the GI Bill afforded more opportunities to attend. Roberts plays a Minnesota graduate student, Katherine Ann Watson, who lands a position teaching at Wellesley (no, this would not happen today) only to find that her students are extremely resistant. What I like about the film has nothing to do with art, or the rather clunky speeches about the importance of understanding sexist culture. The chemistry between all the women, teachers and students (see it for Maggie Gyllenhaal’s bear hug moment) is the selling point and the depiction of a teacher who doesn’t know how to teach yet. Watson’s lectures are caricatures of teaching—hostile but still effective. And teaching can sometimes feel combative. And sometimes students are hostile to someone with their best interests at heart.

In the end, of course, the students come to appreciate her, and they decide she’s pretty much the best thing ever to grace a lecturn. But it’s really a failure of teaching since she only succeeds “by example,” as Kirsten Dunst’s Betty’s final editorial declares. It’s obvious why, but I like to believe that professors might succeed in spite of themselves.

What are some of your favorites? Still Alice? A Beautiful Mind? Good Will Hunting?