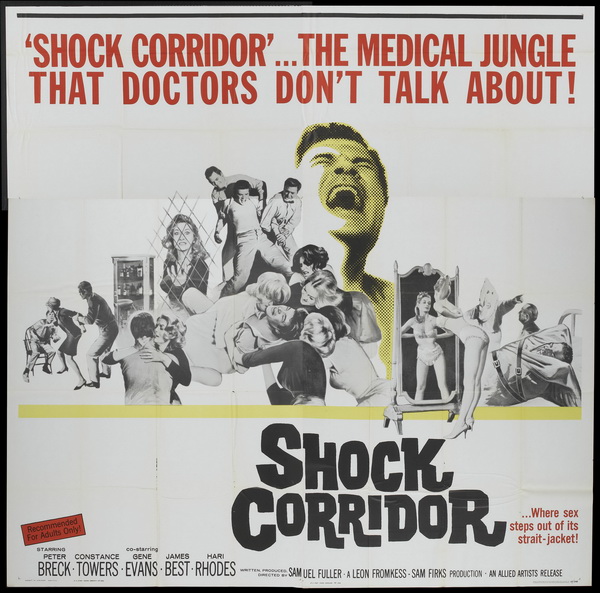

1963 is our "year of the month". Here's Sean Donovan on Shock Corridor

In Robert Polito’s Criterion Collection essay on Samuel Fuller’s 1963 film Shock Corridor, the firebrand filmmaker Fuller is quoted saying “it is not the headline that counts, but how hard you shout it.” This spirit of loud, unabashed aggression perfectly epitomizes Shock Corridor, a singular, strange entry in the cinema of 1963. The film follows an ambitious journalist Johnny Barrett (Peter Breck) who gets himself committed to a mental hospital (after faking incestuous urges in a meeting with psychiatrists) to crack a mysterious murder case from the inside-out, hoping to get the secrets from the inmates on their own level. If it sounds like the makings of a sleazy pulp fiction novel, that’s exactly what is.

Shock Corridor is pure b-movie Hollywood gutter trash, but with Samuel Fuller at the helm, it becomes something fascinatingly independent and bizarre...

Early in the film we get this absurd burlesque song and dance routine featuring Johnny’s girlfriend Cathy (Constance Towers, who got a lead role the following year in Fuller’s The Naked Kiss, a superior film) that epitomizes the pulp anti-glamor Fuller nails so impressively. The camera pans up from a traditionally objectifying image of Cathy’s alluring legs before landing at a bizarre shot of her head. Cathy is wearing a feather boa that is excessive to say the least, so long and bulky that when it’s wrapped around her head she resembles a large muppet. The camera lingers on this bizarre image far longer than it should, with an exaggerated burst of air indicating where her mouth is as she coos seductive lyrics. What is happening? What are we supposed to be feeling? Fuller’s filmography is full of these manic WTF moments that thoroughly destabilize what we’re watching, injecting a note of parody and deconstruction to otherwise straight-faced genre fare.

This straight-faced genre fare takes place at an overrun mental hospital, where the doctors are few and the patients are many. The mental hospital is a step below other exploitation film locations in terms of popularity, but still feels familiar. The stylistic assemblage of Fuller’s asylum in Shock Corridor was perhaps influenced by the asylum appearing in Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s adaptation of Suddenly, Last Summer, released four years earlier, where Elizabeth Taylor, on deck for a lobotomy, played the fragile flower in a sea of barely civilized monsters. The mental hospital is frequently a tasteless zone for Hollywood of this time period (and it’s barely gotten better): parading mental illness as a monstrous vice turning humans into animals, out to destroy the good god-fearing neuro-normative American citizen. It’s offensive and there’s no reason to clear Shock Corridor of this basic crime of dehumanizing sufferers of mental illness.

But it’s equally clear that Samuel Fuller’s film is not a polemic about his fears of the mentally ill. Sure, Shock Corridor is dressed up in the same psychobabble afflicting Hitchcock films at this time (released as it is between two of Hitch’s more psychoanalytic features, 1960’s Psycho and 1964’s Marnie). References to Freud and fetishism are tossed around freely. But for Shock Corridor, the setting of a mental hospital is nothing more than a path for Fuller to write lurid pulpy portraits of individuals hellbent on believing they are something else. The three primary witnesses Johnny Barrett is tracking, whom neatly structure the film in thirds, are all possessed by a theatrical need to act out artificial personalities. The film would be virtually unchanged if the setting of a mental hospital were swapped for a very committed roleplay community. They are Stuart (James Best), a Korean war defector who believes himself to be a Confederate war general; Dr. Boudon (Gene Evans) a nuclear physicist who believes he’s a small child; and, probably most incendiary for 1963 audiences, Trent (Hari Rhodes) an African American college student who believes himself to be the Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan.

In all three Multiple Personality Disorder is implied, but never directly named; Shock Corridor is fine to just dub them “crazy” and call it a day. Hari Rhodes gives a remarkable performance, and is the “just right” of the Goldilocks principle these three case studies create: James Best is too broad, creating such a silly characterization it’s hard to take his tragedy seriously at all, while Gene Evans doesn’t get into the absurd play of Fuller’s world at all, cutting a distanced traditional figure of regret that feels like he’s in the wrong film. Rhodes finds the perfect balance, and is truly chilling even as he submits to the base garishness of the screenplay.

We come to understand these delusions of identity relate back to feelings of political non-belonging that caused a cataclysmic psychotic break: Stuart’s dissent for the war created a hyper-patriotic alter ego, Dr. Boudon’s guilt over Nuclear war created a child totally indifferent to the suffering of others, and Trent’s experience of racism created a raving white supremacist. As Barrett too begins to confuse the boundaries between his identity outside the hospital with his incestuous persona (shades of Shutter Island- who is the doctor and who is the patient?), Fuller’s agenda becomes clear. He’s critiquing war hawk nationalism, nuclear arms thirst, and white supremacy as institutional generations of 1960s America. These structures are holding social justice as a prisoner, just as Barrett comes to be a prisoner of the hospital.

For Hollywood in 1963, Samuel Fuller was bringing something thoroughly unique to the table: incendiary political rhetoric tied to this very gaudy, ridiculous low-culture film. Only in Shock Corridor do you get earnest political criticism of American society next to a room full of loose female nymphomaniac patients singing “My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean” as they attack shrieking men. Before New Hollywood emerged in the 1970s, with its changing standards of reality and political representation, a cluster of movies had to come along to stretch traditional Hollywood styles to their breaking point. Shock Corridor provided a stupid, silly, aggressive way to shake cinematic form to its core.