"The Furniture," by Daniel Walber, is our weekly series on Production Design. You can click on the images to see them in magnified detail. Since the Honorary Oscars are handed out next week, here's a Donald Sutherland film for you!

Federico Fellini didn’t much like Giacomo Casanova, the famously amorous subject of his meandering fantasy-biopic. The director may not have liked Donald Sutherland, either. The actor was required to shave his head and sport both a false nose and a false chin to play the long-winded lover. The costumes aren’t especially flattering either. Fellini’s Casanova is an erotic descent into Hell, a grotesque pageant of 18th century moral abandon. It frequently borders on the disgusting.

Federico Fellini didn’t much like Giacomo Casanova, the famously amorous subject of his meandering fantasy-biopic. The director may not have liked Donald Sutherland, either. The actor was required to shave his head and sport both a false nose and a false chin to play the long-winded lover. The costumes aren’t especially flattering either. Fellini’s Casanova is an erotic descent into Hell, a grotesque pageant of 18th century moral abandon. It frequently borders on the disgusting.

It was also on the edge of Oscar’s attention, sliding into only two categories. While Fellini’s Casanova did win for its costumes, its production design missed out entirely. Anyone betting that year would likely have lost money; La Dolce Vita, 8 ½ and Juliet of the Spirits were all nominated for both.

Though this sexualized panorama thrilled the costume designers, it may have shocked too many art directors. Like Sutherland’s performance, it’s proved to be a bit too much for the Academy. That’s a shame, because the contribution of legendary designer Danilo Donati is dazzling...

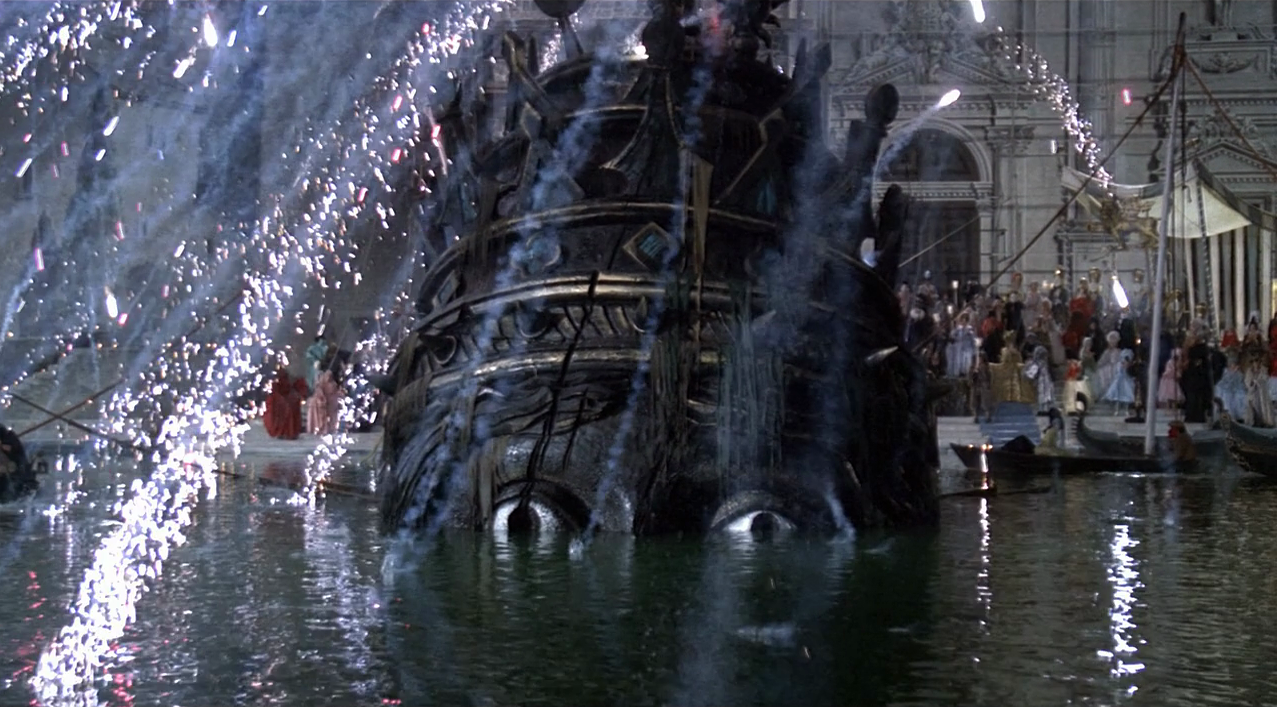

The film begins during the Venetian Carnival, the biggest party of the year in Casanova’s hometown. A studio replica of the Rialto Bridge is packed with masked revelers, eagerly awaiting the birth of Venus.

Her monumental head sits beneath the surface, slowly rising as the Venetians drag her up with ropes. But something snaps and she sinks back down. The festivities turn to panic. It is an horrible omen, for both the city of Venice and one Venetian in particular.

Like many of Fellini’s metaphors, it a grand marriage of shiny magnificence and transparent falsehood. This is a Venice of colorful fireworks and obvious matte paintings, a wonderland of barely attempted authenticity. Even the lagoon turns out to be a shimmering forgery.

It is like Casanova’s reputation, a caricature drawn from the cheap virtues of sexual prowess. Eventually it will drive him to bitterness. He sees himself as a great statesman and intellectual, but no one else buys it. Even his moments of occult conquest are undercut by the silliness of both his clothes and his surroundings.

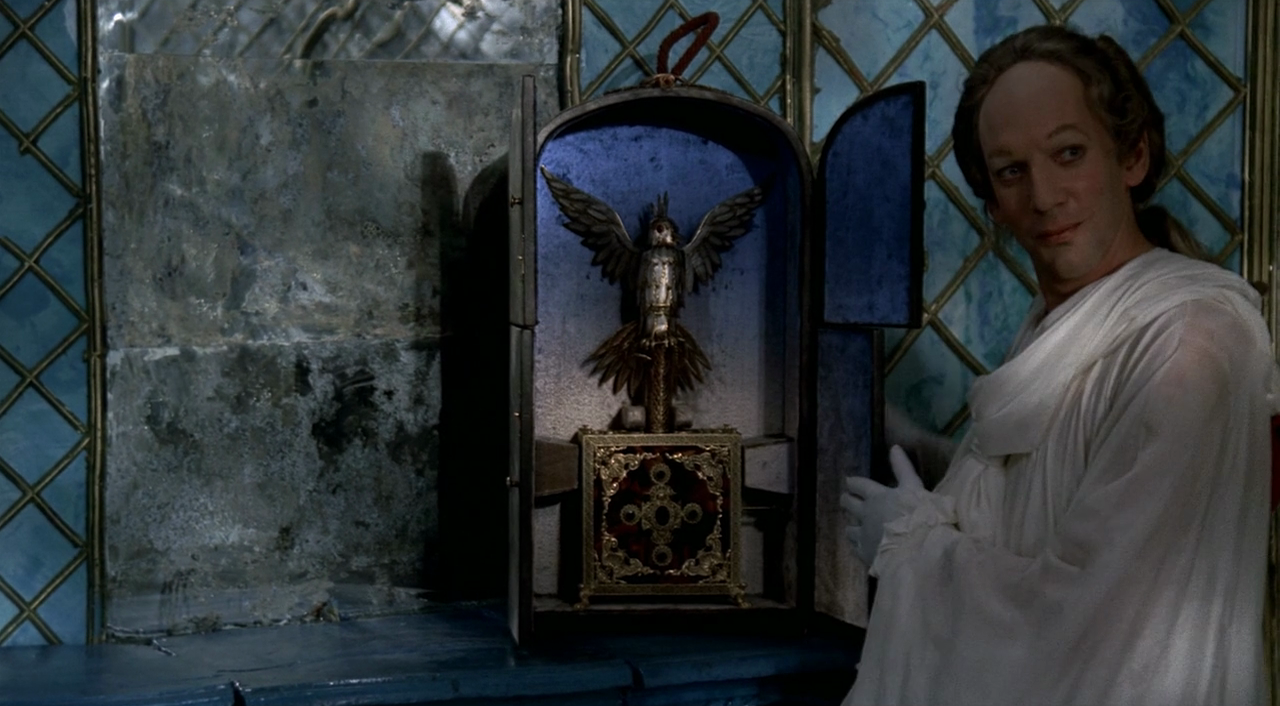

He accompanies each sexual experience with the crowing of this mechanical cock, whose jaunty robotic tune is bizarre even for Nino Rota. It’s the film’s best prop, a perfect symbol of Casanova’s blissfully preposterous dilettantism.

But if the film is a harsh critique of one man, it is also a picaresque indictment of Europe’s useless gentility in general. Each princely court is more depraved than the last. Sour wine is spilled on the finest of its arts, the cultural legacy we are often told is the mark of great civilization. Here, everything from Bach and Dürer to Monteverdi and Velázquez seems like the miraculous accident of a continent bent on drowning itself in a vat of Early Modern vomit. This is almost literally true at one of these parties. Revelers sprint across an over-decorated portrait gallery, their cheeks full of wine.

A parody of Dürer’s famous rhinoceros stands behind a towering pile of pasta and impossibly large salami.

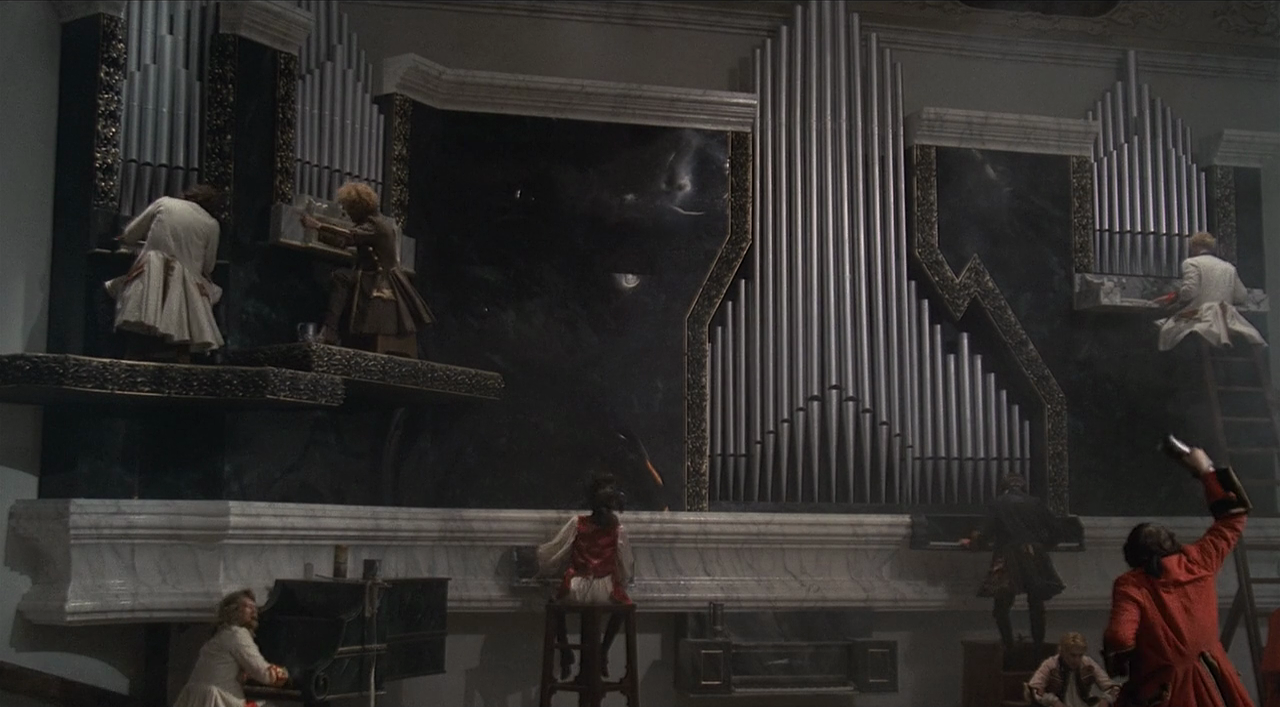

The grandest, most absurd of these perversions is found in Saxony, where a German prince presides over a smoky, drunken mess. There is an entire wall of organs, some of which sit so high up that the musicians need a ladder to reach their keyboards. They hammer away all at once, an infernally fugal racket.

This design is out for the kill. But it is not entirely without charm. Even this, Fellini’s most sour film, still holds a wry smile and a unique sense of fun. My favorite example is that of a magnificent opera house, its stage full of extravagantly-dressed mythological figures crowded beneath a triumphant sun. It’s a resplendent symbol of this supposed Age of Reason.

But the show soon comes to an end. The candelabras descend and group of working men arrive with enormous black fans. They meander about, flailing their implements until the candles are extinguished. As this palace of culture falls to sleep, the wax collects on the floor and the colors fade. Like Casanova himself, it returns quite unromantically to dust.